After viewing the simply captivating The Wondrous Willa Kim: Costume Designs for Actors and Dancers at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts (which I wrote about here), I wanted to learn more. I reached out to the curator Bobbi Owen for an interview, and read her monograph of Willa, The Designs of Willa Kim, published in 2005. A slim volume, it focuses on explicating the many various productions Willa worked on each year of her multi-decade career—illuminating how much much Willa worked and how varied the styles she created were.

With such a huge output, choosing what to include in a retrospective exhibition can be difficult—I wanted to speak with Bobbi to get a sense of how she approached curating this show, as well as more about her personal experiences with Willa. As you’ll read below, Bobbi and Willa became friends after Bobbi reached out to her while working on another book, Costume Design on Broadway. Bobbi taught costume history and design for over 40 years at UNC-Chapel Hill and since her retirement in 2021 is the Michael R. McVaugh Distinguished Professor of Dramatic Art Emerita. She is the author of nine books on theatrical designers, covering not just costume design but also lighting and scenic design. Her monographs on Willa Kim and costume designer William Ivey Long were part of a series published by USITT (United States Institute for Theatre Technology), The Designs of…, which can be purchased through its website.

Bobbi and I cover everything from her own background in theatrical design, her friendship with Willa, Willa’s work and how Bobbi approached writing a book and curating this exhibition on her, as well as discussing other costume designers Bobbi admires and the digital costume archives that Bobbi helped develop at UNC.

If you are in New York, this coming Monday, April 17, Bobbi will be giving a talk at the Library for the Performing Arts centered on showing Kim’s work in motion, through “performance footage from works preserved in the Library’s theatre and dance moving image archives.” Friends and collaborators of Willa’s will be joining her for the discussion. You can register for the event here. For more on Willa’s history, check out her NYT obituary.

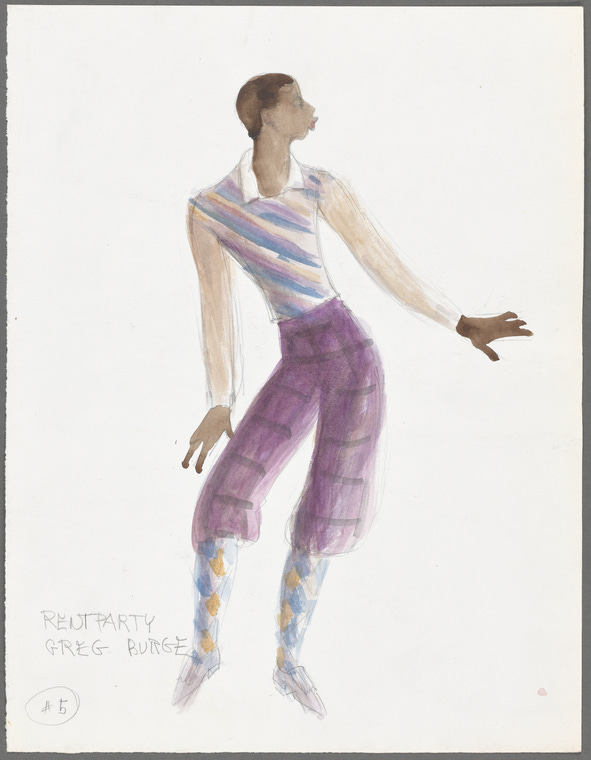

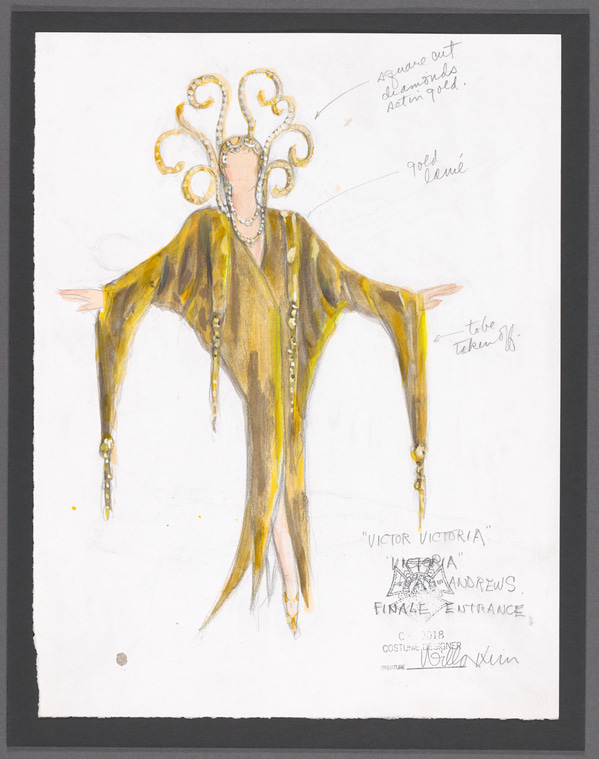

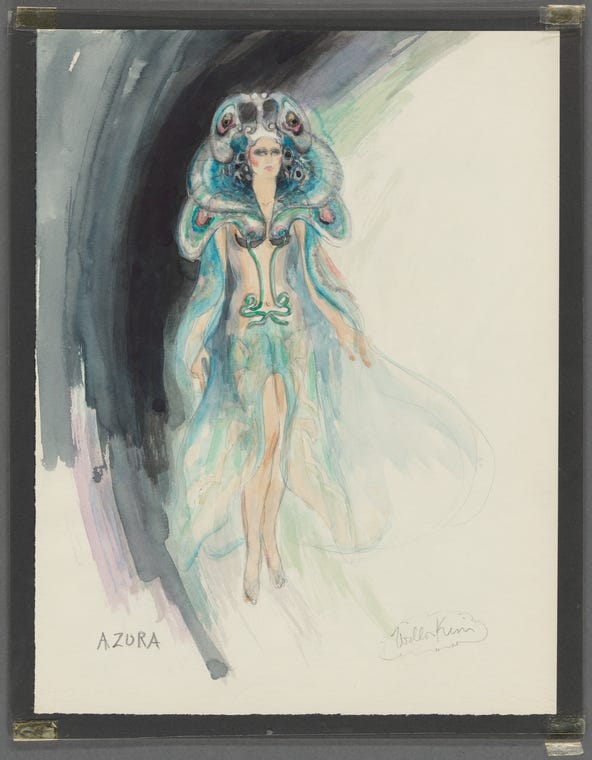

All of Willa’s sketches below are from the Willa Kim archive in the Billy Rose Theatre Division at the NYPLPA. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Laura McLaws Helms: I loved your exhibition. It was so wonderful seeing the costumes in real life, and obviously the drawings, sketches and everything.

I know you studied theater design. What drew you to theater design in the first place? And how did you move from then theater design into the researching and the history of it?

Bobbi Owen: I was a pretty typical undergraduate student who majored in English. I really thought what I was going to be was a high school English teacher. And as part of the requirements, you had to spend a couple of big blocks of time backstage because I think they believed that it would be helpful. My high school English teacher was the play's director when I was there. So, I went to the costume shop, because I knew how to sew, and really never left. It was like, "Oh, my goodness, you can put together what I loved—art history and history." And I was able to draw, and so all of those things just really came together for me. And I never pursued teaching high school, I instead pursued teaching college.

So, in the world in which I lived, for all those years, it was publish or perish. You couldn't, you know, you can't have an academic career without being able to do those things. And I did. My original goal had been to write a book about all of the great 20th-century costume designers who started that profession. And along the way, I got really distracted, because I didn't know who they were first. I ended up doing a couple of books about a whole bunch of costume designers. Costume Design on Broadway was the first one. And then as my career developed, I really wanted to start focusing more on individual designers. And that's what led me to Willa Kim. When I did Costume Design on Broadway, I wanted to put illustrations in the book from many, many costume designers. It wasn't long after she had won the Tony Award for “Sophisticated Ladies.” I called her up, I really just literally called her up and asked her some questions, and she invited me to come over and visit with her. And we became fast friends. And so, when I was interested in doing an individual book about a designer, it was very logical to start with Willa. Broadway Press and USITT were interested in that monograph series, and so it was just fabulous for me. Willa and I became very good friends. I would write during the week in Chapel Hill, and I would fly to New York, and we would spend weekends together and I'd come back to Chapel Hill and I'd write some more and I'd go back and see her.

Amazing. What was she like in person? From what you wrote in the book, she sounds really warm and like a wonderful person.

You know, I never made costumes for her, so I didn't quite see that formidable side of her. But I did eat tofu for the first time ever because of Willa Kim. She was rather amazing. We had a really warm relationship. I got to know lots of people who loved Willa as well, and that made a big difference. People were very willing to talk about her. I think I was there at a really fortunate time in her life and career when she was willing to take time with me. I know that had she been busier and times when she was busy that just, you know, her work came first. And so, it was easy to push me aside. I was glad for her to be able to do that. Because she was such a perfectionist, I think that she was harder to work with, than she was to know as a person, although she became very, very good friends with a lot of the people that she worked with as well. And on the 17th of April, when we do the talk there are going to be some people there talking about how exciting it was to work with Willa and I think how demanding she was. Perfectionists and artists, I think always are really actually that way.

Did she put any of that perfectionism towards your book, the monograph?

You know, she certainly had strong opinions about what she wanted in the book and what she didn't want in the book. Reading it there's not as much about her personal life as I might have wished there would be but she was also very private. You will be amused that for many years, she talked about her "older brother." Her family—you know, she had brothers and sisters, her parents. She was close to her mother, and I think that was sometimes a little bit difficult relationship for her. Her brother, Young Oak Kim, became a Colonel, and had an amazing career during the Second World War, he was much decorated, albeit later in his life instead of when actually that happened. He talked about his older sister, and so Willa had to come clean that in fact, she was the oldest child in the family, and she was actually older than she had been leading people to believe. I'm not entirely sure that we know exactly when she was born, because one of the people who is managing her estate told me they found several passports, and they all have different birth dates in them. We have one that we're sticking to and we're sticking to that. We know that she was just less than 100 years old when she died. That's amazing. And at the end of her career, she was saying, "Why aren't people calling me? I want to work, I'm ready to work. I want to do more stuff." And so that kind of creativity that really filled her entire life never left.

When did she stop working?

Well, “Turandot” was her last major production. And I think that was 2005. At the Santa Fe Opera. Everybody kept talking about the “Red Eye of Love” might come back, and she was really interested in that and had lots of meetings about it. But what was she, 90 years old when she stopped working? We can all aspire to that.

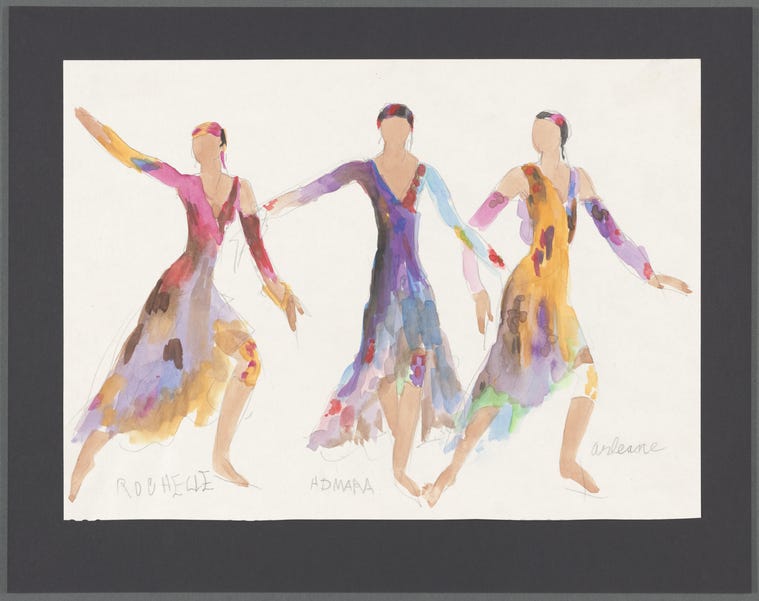

Amazing. I mean, very few people can manage that long of a career and that full of a career, just the amount of different things she was doing every year across all of these various fields from theater to opera to ballet. Incredible. Do you have any favorites? Your personal favorites of her work?

Oh, my goodness. You know, that's so hard to choose. In the course of spending time with Willa, I probably began to admire more how she used things from her background as an American of Korean descent—that she had an affinity for productions like “Turandot,” although that's China. It's Italian-Chinese, so it's a little mixture of things. But I think she had a sensibility about color and detail that you could trace to her background and her love of that, the love of color that she had really came natural to her.

How did you choose what productions to focus on for the exhibition at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts?

The library was very supportive of having costumes be added to the exhibition. Libraries and museums really want to exhibit their own things. They don't want things brought in from the outside very often. But Doug Reside was so helpful in understanding. He understood that it's very hard to have an exhibition about a costume designer without some costumes in it. That no matter how beautiful you can draw, and Willa Kim is an amazing artist, right? She draws beautiful things.

Because I wanted to have costumes displayed, I wanted to make sure that the designs that were executed, also had related costumes. So, I started looking for the costumes, I started looking for things that I can find. And then was able to also use the library's great resources for photographs to accompany those as well. I put out feelers to a lot of friends and colleagues about where they might know that Willa Kim's things might be. Goodspeed Opera has a large rental business, and they buy Broadway productions after shows close. And so there were things that were available there. They also are in the business of renting them, and so there were some things I might like to have used—more things from “Victor Victoria” but they got worn a lot and therefore they weren't in beautiful condition. And I think there's nothing sadder than sad costumes, they really need to look fresh. They need to look—even if they're 40 or 50 years old—like they are, you know, brand new. I was lucky that I liked “Legs Diamond” as much and I could find many things from it. It was a flop. So, it meant that those costumes were only worn for like 50 shows on Broadway, which meant that they were considerably fresher, although Goodspeed rented many of them for other productions. And so, we had to refresh some of them that I was careful about what I chose to use.

I wanted from the beginning to use some things from her dance career. And Feld, Eliot Feld kept all of the costumes in the repertory. I spent some time with Maggie Kristen and other people at Feld studios to see what it was that was there. I always loved the “Papillion.” And so, because they had that costume, and those baby butterfly wings, it was early on going to be one of the centerpieces. It was an easy choice because they had that. And then with the help of Sally Ann Parsons to be able to construct the web behind it, it was just a great way to center what the exhibition was going to be. Tony Walton, who was one of Willa's great collaborators had done the scenery for “Sophisticated Ladies,” and I originally hoped that we'd have the model for the set for sophisticated ladies. But when he went to his storage place to see it, it was really sad. It would have to have been almost completely remade. And that was too much to ask Tony to do. But the “Peter in the Wolf “set model is really extraordinary. After he did that model, and Willa designed the costumes, he did all of those little tiny figures to put on the model based on her costume designs. It was such a nice synergy between the two of them that that became a very useful thing to do. “Sophisticated Ladies” was possible to find some things for and because she won a Tony Award for it, it was really an important thing to have.

I found some things for “Will Rogers Follies,” but “Will Rogers Follies” has not aged very well. 1991. If that musical was being proposed today, I don't think it'd be done. The racism of it, the sexism of it, are things that we certainly should talk about and contend with, but it seemed less appropriate for them to be in that. She did win an award for it. And nobody is dismissing, I think, the fact that she really deserved the Tony Award that she got, it's just a problematic musical.

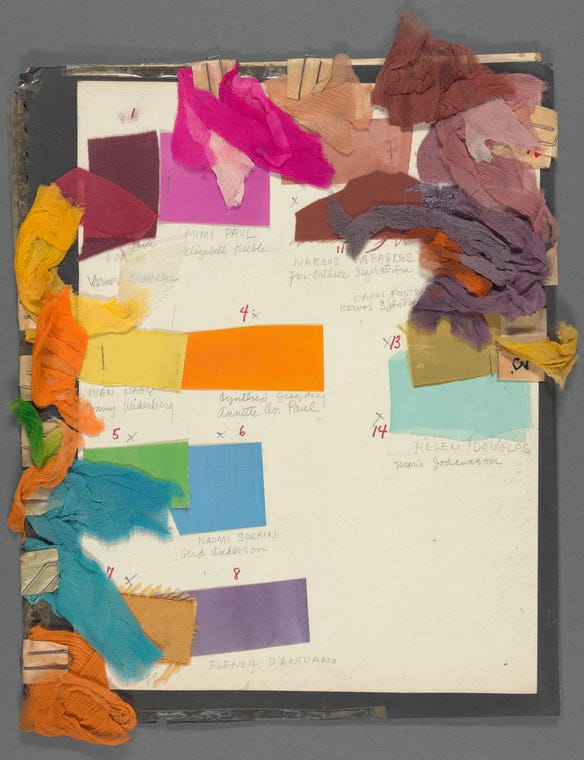

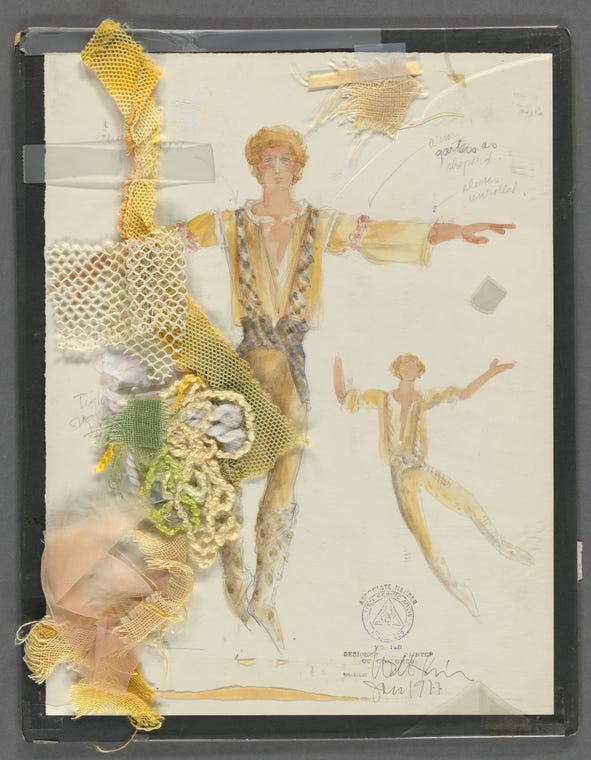

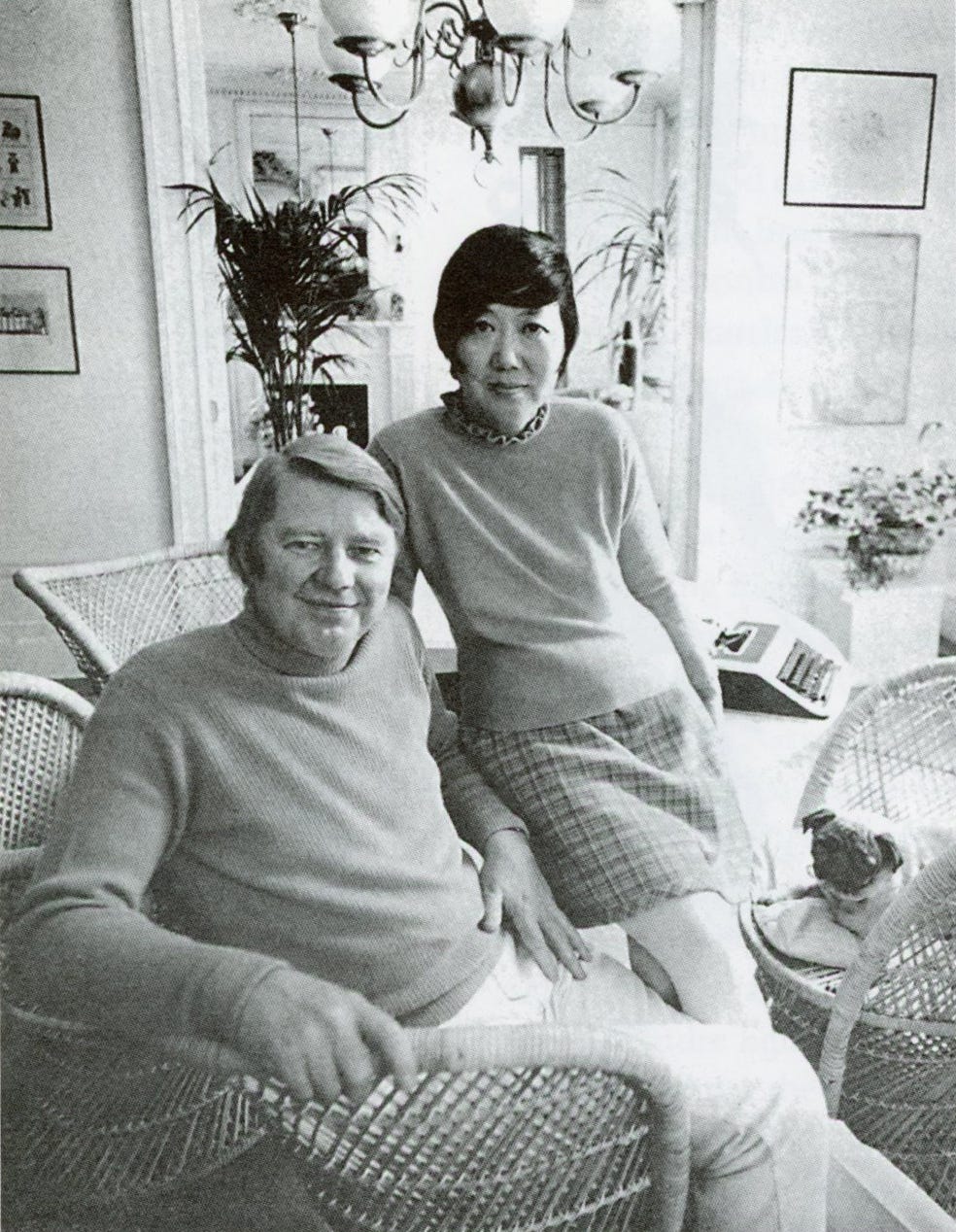

The other thing I'll say is that Willa from the beginning of her career, never would use a piece of fabric out of a fabric store straight off the bolt. It always had to be manipulated. You can buy a beautiful piece of fuchsia silk, but if you dye silk fuchsia, you get a considerably more vibrant color. So, fabrics always had to be beaded or sewn on or ribbons added or dyed or painted, sometimes all of the above. And I wanted to be able to show her process from the very beginning. Caitlin Whittington who designed the exhibition understood that and that wall of swatches, the wall of samples really was based on an idea that Caitlin and I both had together. And I think it's a really successful part of the exhibition. I love that when you walk in the exhibition, you don't see it. And you move around the exhibition, and then you find yourself at that wall. And it's a big kind of culmination. Sally Ann Parsons also made so many of Willa's costumes that to have that widescreen photograph of Sally Ann Parsons and Willa together was just ideal. Willa had a copy of that photograph at her house, and so it's something that I was aware of and was really glad to be able to use.

I loved that wall and the photo together and then the sketches embedded in amongst the swatches—it gives you a feeling of being in a studio, and sort of surrounded by what she would have had all around her.

Oh, Laura, I'm so glad to hear you say that. It was fun to create that wall, to start with basic swatches that came out of fabric stores—you can see price tags and sources on some of those. And then to do more and more manipulation until you got into things that were actually painted. If we were there together, I would be telling you what they were all from, but there are beading samples from “Victor Victoria.” I know that a sample of what Bernadette Peters wore in “Song and Dance” is on that wall. So, you know, it really worked well and I'm glad that people are responding to it. I knew it was going to work because when we were installing the exhibition, the guards kept coming through and they always have wonderful questions about things and comments about things and how colorful it was.

How did Willa's archive come to be at the library?

I can say that Willa wanted—she didn't give sketches away, she kept her archive really close to her heart and close together—that she wanted it to be someplace in one place, instead of dispersed, which has happened so often. And I think that toward the end of her life, a couple of the representatives from the estate had a conversation with Doug Reside at the library. I've heard Doug say that it was the first thing, when he became the head of the theater part of the archive of the New York Public Library, that he was able to bring into the library.

So, he was approached, and then after she died, the archive came. When I was starting to put the exhibition together—he approached me, I think, because I wrote the book, literally, I wrote the book about Willa and so it was a logical thing for that to happen. It was such a treat for me. I was out in Long Island City when it was being cataloged, and so as things were starting to get opened and they were starting to go through stuff, I was lucky enough to be there when that was being done. And so, I could start to think early on about what I wanted to put in the exhibit.

You were probably, because you wrote the book, able to help them in their cataloging.

I was certainly able to answer questions, but Willa was meticulous about having documented and kept things together. One of the things I'm so glad the library did was they accepted her notebooks. I mean, if you saw the Baryshnikov... so you can see that she would draw, you know, she would go in to see a rehearsal, and she'd just be there doodling away on any piece of paper that she had to hand. And I think there's something like more than 45 books, notebooks that she filled with sketches. And so, you can see her brain working on that. You can see the research materials that she was approaching, you can see the designs as they started to come together. And then the fabrics that really made them possible.

What an amazing resource all of those books are and all of the whole archive.

Absolutely. I mean, there's lots of Willa's and there are lots of exhibitions that could be done. This one really focuses on her use of color and texture.

Do you know if she had a personal favorite of her designs?

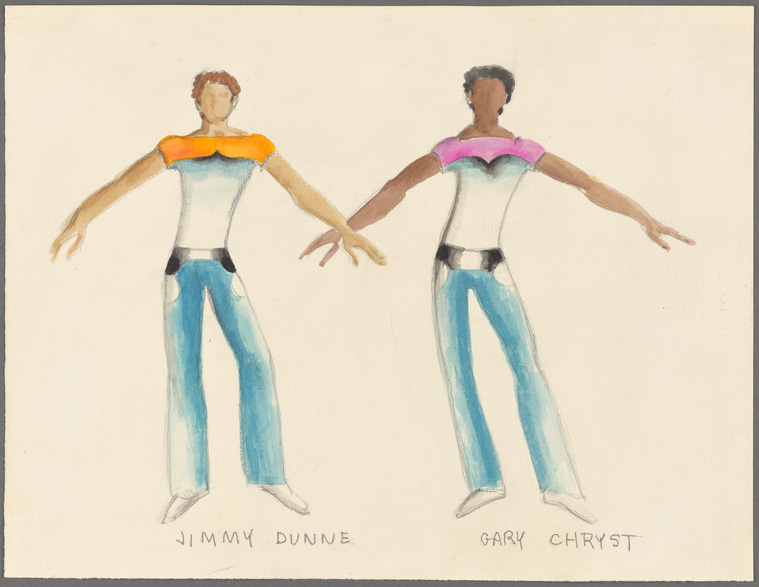

Oh, I asked Willa that question several times and she answered it differently every time I asked her. I think she was especially gifted with doing dance—whether it was in Broadway musicals, or was for what she called ballets, or whether it was for ice skaters—that she was always so gifted at being able to enhance movement and never inhibit it. I mean she wanted somebody to wear a pair of blue jeans—spandex jeans would be made. And then all of the rivets would be put in them, all the stitching would be done on the pockets. And you'd end up seeing somebody wearing a pair of blue jeans that were—and I'm not talking about today, I'm talking about something that would have happened 40 years ago. Or she wanted a pinstripe suit put on a gangster. It would be reproduced in materials that could [move] then the stripes would be all painted on or would be done in a way. The “Weewis” costumes look like a pair of jeans and a T-shirt, but they're movable. So, I think that she's especially good at dance. I think, if she were answering that question today, tell us that she loved doing opera. Because the palette for opera, the scale of opera is huge. So, she could just let everything go and do big canvas things. The answer just kept changing.

In your book, you wrote that she didn't really do film again, because film takes such a large time away from other things. You mentioned she did some gowns for Garden of Stone, but did she ever have any interest in going back to film after starting her career at Paramount?

I think that she found the movie studio life boring. That it was, you know, she said she went to Paramount because she could draw so well. She was working in the May department store and somebody just really enticed her there. I don't think she would have stayed very long, because I think she found it kind of tedious. But there she is walking down the hallway and suddenly she sees these really beautiful designs. And it’s Raoul Pène Du Bois that really captures her imagination. And she is oohing and aahing over them and Karinska, who Raoul had brought from New York out to Hollywood, realized that Willa was interested in that and just took her right on. So when Karinska and Raoul came back to New York, Willa followed them. Because I think she was really compelled by the magic of that. I don't think she ever looked back. And as you say, the time it takes to do movies is extraordinary. I mean, mostly what she did for television—and she won awards doing television, I think she would have won awards doing movies—was recreating what had been done on stage. You know, mostly opera. And so that Santa Fe, that Great Performances stuff she was recreating what she had done.

I'm really glad that they were able to do some of those productions for TV and so that we have them now. I know in the book, and as you mentioned already earlier, she was very private person. I always sort of wondered how her and Billy's relationship worked. Once he moved to Europe, they were still together, right?

They never divorced, right. They remained friendly and in close touch to the end of his life. And I know that Billy had a sister with him, Willa was also close [with her]. And so, I think their lives in some ways went slightly different directions. They had had a really whirlwind romance at the beginning, and I think that excitement never left. I think she was an important part of Paris Review. That the way that his art direction of Paris Review went... it's within the last ten years that she did a retrospective in Paris Review of her own designs. And, I think that relationship stayed really, really important. And that connection stayed really important. I think she had some other friends as did Billy. But she was circumspect about those. And I'll be circumspect about them as well.

It sounds like her work, and creativity, was by far the most important thing in her life.

Right. And I think that's exactly the same thing we'd say about William—his life and his creativity. They found places for each other in that.

What other costume designers do you really love from the whole history [of costume design]? That you're the most passionate about?

Oh, what a good question. There are lots of costume designers that I admire for very different reasons. I think that William Ivey Long is a really wonderful designer. And you know that I've done a book about him as well.

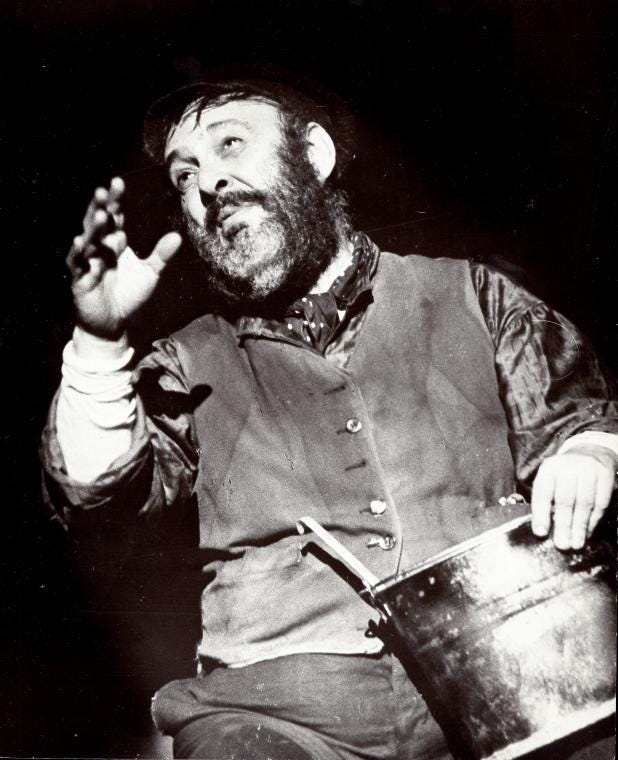

I have always been a fan of the ways that Patricia Zipprodt could do something like “Fiddler on the Roof.” Do you know the story about her? When she was doing “Fiddler on the Roof,” she thought the costumes were way too clean and way too nice. She would carry them away and she would rub sandpaper on them. She would use cheese graters; she would take them out in the street so that the buses and taxi cabs would run over them. She would disassemble them. And then the next day, she would take them back to the workroom and ask them to put them back together. Because they had been all distressed and mangled. And Barbera Matera, who made those costumes, had to convince the women who were first hands and stitchers to touch those really ugly dirty clothes because they were so used to making beautiful things. So that when “Fiddler on the Roof” ended up on stage, it looked real, you know, it looked... I'm not a fan of going to see movies where there are huge gunfights and battles and everybody's face is perfect. Or they get just a little smudge of dirt on it instead of it really looking dirty. You know, and that's all paint. And so, I admire that way.

I admire the way that Theoni Aldridge was able to do really beautiful period costumes. I think Jane Greenwood is exactly the same way. That it's like they are living in the 19th century and know those clothes so beautifully, that they're able to put those things on stage. I think that the kind of design that I like the most is seeing people from other periods wearing those clothing forms.

I'm interested in a 19th-century designer named Percy Anderson, who did all of the original Gilbert and Sullivan operas. You don't know his name—nobody does. But I've been kind of slowly working towards something about him because it's the beginning of the profession. You go back to the 19th century, you know, there it is.

I will not let us stop talking about this without saying Tony Walton. Tony Walton was mostly a set designer, but he also was the art director for lots of movies like Mary Poppins. And he did both scenery and costumes for things. I think if you pushed Tony, to say what it was he liked the most, he liked doing the art direction and the environment. And he was very happy to collaborate with Willa Kim, who can inhabit it with costumes. I also admire that brain that really understands all of those things, and it's because of Willa that I get to be close to Tony Walton and his wife, Gen LeRoy.

I know that the books on William Ivey Long and Willa Kim are both in a series. Are there going to be other ones in this series?

I think that USITT has decided that they're going to focus on digital publications right now instead of more of those monographs. The Late and Great book was an attempt to kind of catch up with some of the designers. When we did that monograph series, you had to be alive, and available to have your archive be part of it, And that's true of Ann Roth and Santo Loquasto. And so, the Late and Great book was trying to catch up with some of the people who are no longer with us. Raoul Pène Du Bois is actually in it, he's really another amazing designer. He did the original “Music Man,” he did the original “Gypsy.” Musicals that keep being reinvented, who were the people who did those originally? That's rather extraordinary. So, Percy Anderson is kind of the person that I'm most interested in right now. His archive is spread all over the world, so it's unlike what the New York Public Library has in Willa Kim.

That sounds really fascinating because I've never heard of him before, but to find the first one of the people that's sort of the beginning of this whole career field, it's incredible to think about.

And it's interesting to think about what Covent Garden was like when it was filled with costume shops. you know, all those work rooms were around Covent Garden, then they could just carry them over to the opera, they can carry them over to the theater. Like New York, like the garment district was in New York.

To finish all of this up, when I was reading your bio on the UNC site, I was really intrigued by these online archives that you set up, Costar and NowesArk.

So, every costume shop in the country, at universities, and colleges and community theaters, people give donations of clothes, right? And Carolina is the oldest public university in the country, so things here go back to the 18th century. When I joined the faculty in the early 1970s, there were things that were precious, but that could not be worn on the stage. Once, I opened a box and there were newspaper articles and documentation for the dress, a beautiful ball gown from the middle of the 19th century that Mrs. Stewart wore to Lincoln's second inaugural ball. I mean, I'm touching this, right? Here it is. Well, it was so precious. And actually, I sent it to the Smithsonian, because it was not something that really needed to be there. But it made me start to look at other things that we had in our collection that were too precious to be worn on stage, too small, too fragile. And those things could be used for graduate students and even undergraduates to understand what those materials were and understand how they were actually made. And so, we started to just first put things away, and then started to find ways that we could share them. And the whole purpose of Costar, the costume archive, which is what that stands for, was to make sure we were taking pictures and documenting things. It is a study collection so all the stuff can be touched, it can be handled, but if you don't have to handle it, that's good. The photographs were very helpful with that, and the details that we're able to do.

NowesArk grew out of my interest in teaching not just Western costume history but teaching costume history from around the world. I've always traveled really widely, so I would just bring things back with me. And if you let people know that you're interested, they would start giving me things. There's a professor on my campus, who was in the Peace Corps in Kenya, and she collected beading samples from the Masai people and gave me one of the capes that she had collected made of goatskin, and now I've got this really amazing thing. People would just bring me things. I had friends for a long time, a professor in the physics department who was originally from India, and he would go back to visit his family in India and he would bring me sari. So, it would be just really fortunate that way. Sometimes people just want to give you their old clothes, but once in a while, they would go into the attic, and find something that was really extraordinary and bring it along. I think we've had a lot of depth to the 1920s. And we're starting to work on 20s things.

When my friend Judy Adamson, who was also part of doing that collection [when she was] at Chapel Hill, went to work at Barbara Matera's they were doing the Broadway production of “Singing in the Rain,” and they were looking for beading patterns. I sent them a box of 1920s costumes from our collection, and they did color Xerox patterns off of those dresses that were then in “Singing in the Rain.” So, it's useful, right? All those things are useful. And we've started archiving them and the graduate students in the production program here will examine one 19th-century garment in detail, and they do a modern reproduction of it. So, it’s getting used. Even though I retired I go one day a week into the drama department and work with a graduate student and an undergraduate student to continue the archiving process. Now I'll do that for a couple more years.

Fantastic. What a great resource.

I'm so glad you've noticed it and looked at it. There's some really special stuff there.