Mary McFadden — Cultural Modernist

In my newsletter earlier this month on Mary McFadden’s hosting style, I mentioned that I had interviewed her in 2013. I received quite a few requests for the interview, both as comments or over email, so I am including it below. That year the Ornstein family, the then-owners of the Manhattan Vintage Show (it was sold in early 2022), told me they were interested in doing something on Mary for one of their shows. I called her up and it was decided that I would interview her for the show’s brochure and curate a small exhibition from her personal archive that would greet all shoppers as they entered the building. In her apartment, I dug through a very packed closet and tightly packed bags of tremendously beautiful garments—no perfectly organized archive for her at the time—to exhibit as prime examples of her oeuvre and hopefully inspire vintage shoppers to start collecting Mary’s designs. If I am able to find photos, I will send them out in the future.

Below is the interview as published. For more on Mary, I recommend the beautifully designed and infinitely inspiring Mary McFadden: A Lifetime of Design, Collecting, and Adventure, published by Rizzoli in 2011.

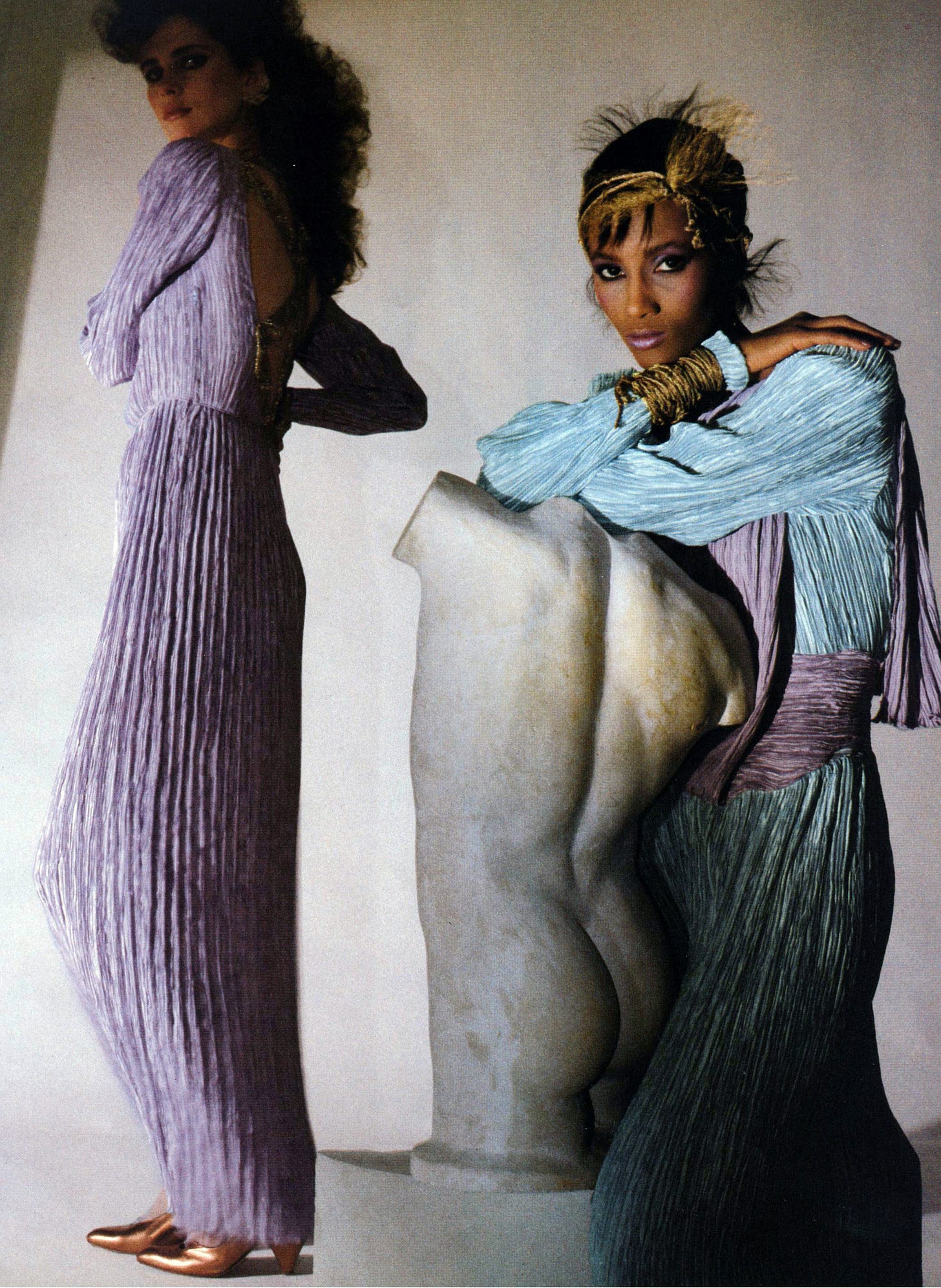

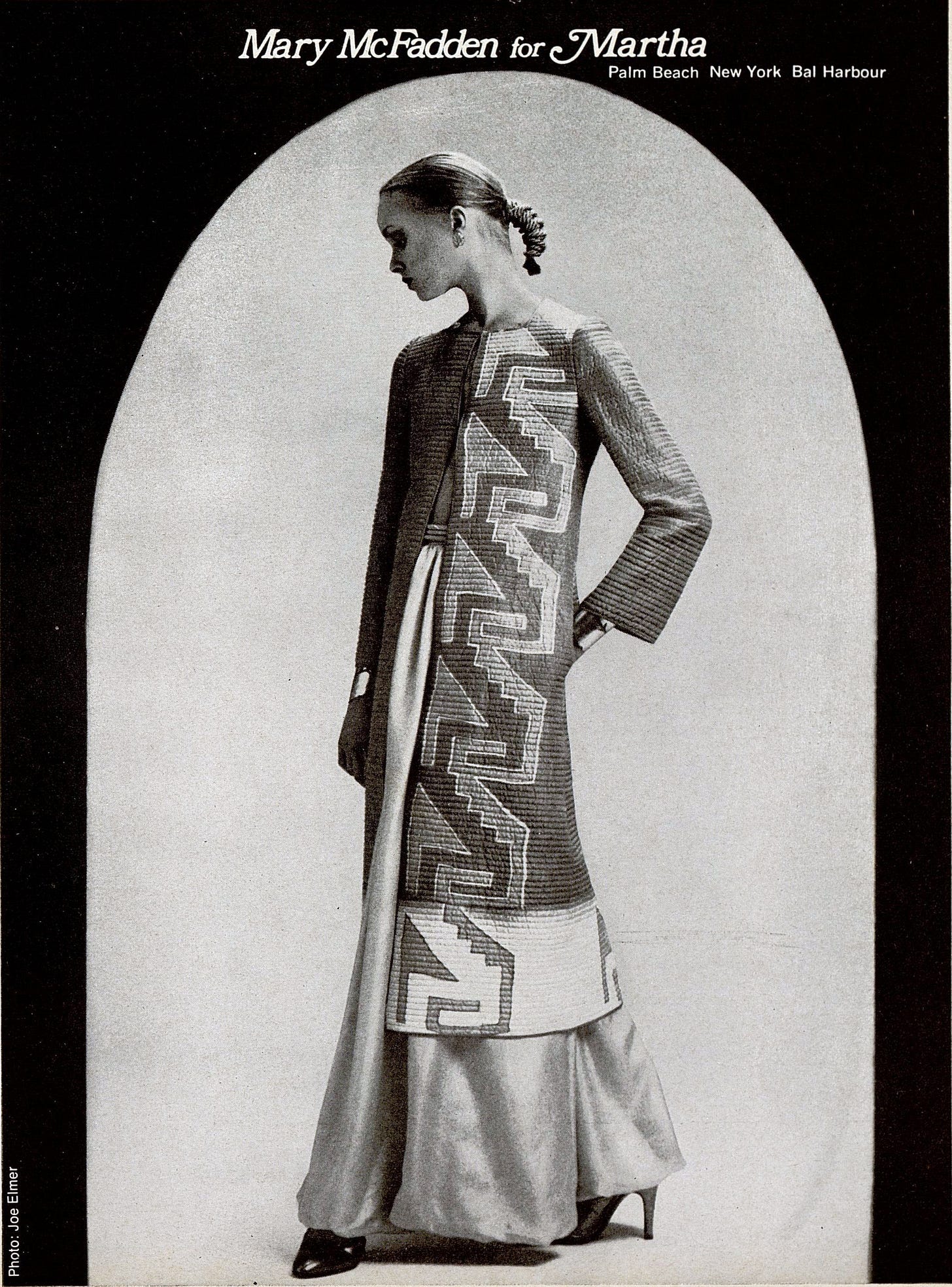

The spellbinding and intricate designs of Mary McFadden occupy their own place within fashion. Laden with historical references, McFadden found a way to blend a vast array of inspirations into designs that appear timeless. While her clothes resonated perfectly with the period she was designing in (1970s-1990s), the use of classical line and form has allowed them to maintain their wearability today. Equally intriguing as her designs is McFadden’s life — raised in Memphis and Long Island, she worked as a PR for Christian Dior New York before marrying a director of the South African diamond company, De Beers. After several years of working and living in Africa she began to have her clothes made using local fabrics, which made a splash when she returned to New York and a job as special projects editor at Vogue in 1970. Henri Bendel came calling and from there she designed couture and ready-to-wear collections, and created an empire of licensing deals that included linens, jewelry and all types of apparel. With her ‘Marii’ pleated dresses, McFadden created a trademark style that made them a favorite of society ladies who were attracted to the unequivocal elegance of them — Jacqueline Onassis wore a white strapless pleated McFadden sheath to the Met Ball in 1976.

Though she closed her company in 2002, 74-year-old McFadden [Edit: now 84] is still actively engaged with the world — when I met with her she had just returned from a solo trip to Bhutan and was about to leave for the Venice Film Festival. Captivated by the ancient world, she is working on a scholarly book on ancient gold (of which she has a large collection). Her Byzantine-inspired apartment high above Manhattan — filled with non-western artifacts and glimmering gold — reflects the myriad of influences that contributed to making her designs so individual and exemplary among her peers in American fashion.

LMH: Starting at the beginning, do you feel like your childhood in Memphis had an influence on your later life?

MM: I lived on a cotton plantation so there was no thought of clothes — it was just going to school, playing with your horses and the dogs, so it was a very agrarian kind of life.

LMH: So your introduction to fashion was when you moved to New York?

MM: No, when I was young my grandmother invited my cousin and I to come to Paris and she took us around to all of the [couture] collections so I got to see Balenciaga and all the collections when I was 13 and 15. Then I worked for Dior when I was 19 so I was very familiar with French couture.

LMH: When you were 13 how did you respond to this introduction?

MM: I didn’t really respond to it then but when I went to live in Rome for a year, where all the women were very involved with fashion, then it became important to me. I saw how fashion was really important in a woman’s life, but it hadn’t become important to me until I saw and was old enough to see how these women spent all day trying to make themselves beautiful. I’m a country girl – you didn’t think that you would spend all day having your hair done and your makeup done. You wouldn’t think that picking out a dress would be really important, but it is.

LMH: You’ve always been known for being very elegant and been included on Best Dressed Lists — did you create this look yourself or did things you saw influence you?

MM: Well, when I went to Rome I realized that fashion was important, but I had no idea that I would ever be a designer. That happened just by chance — I thought I would be a journalist most my life and spend more of my time touring around the world, doing stories, which is what I was doing. It only happened by chance that I got into fashion, because I had made these clothes in Africa; otherwise I would have just stayed as journalist.

LMH: You moved to South Africa because of your husband? Was it a really dramatic change going to Africa after being in America?

MM: Right. Well, I had two fantastic jobs so I had a better time in Africa then I was having here. South Africa is very civilized and I was [merchandising] editor of Vogue South Africa so I got to see the country [1964-65], and then I became a political journalist for the Rand Daily Mail so I got to see the world [1965-68].

LMH: How developed was Vogue South Africa?

MM: I think it was started in about 1960 and closed down about 1968, because Mr. Patcévitch, who was head of Condé Nast at that time, thought there was going to be an immediate civil war in South Africa. I told him at the time it would be at the turn of the century but he didn’t believe me and I was right.

LMH: When you were working there were you meant to mainly focus on European fashions?

MM: It was all South African fashions. There were three stores that had designers working in them so I could take the merchandise from those stores. I could also use local, indigenous fabrics that were basically done in the patterns of African style but manufactured in England. England actually supplied all of Africa with their cotton printed textiles based on their ancient designs. In Africa I started making clothes because I couldn’t find any [that I wanted to wear].

LMH: Were you at all inspired by the couture you saw as a teenager when you started designing? Or what you saw when you worked at Dior?

MM: Well, you see, I couldn’t make those kinds of clothes — I didn’t have a factory or facility to be able to make a couture dress. All I could do was use the Bantu labor to make a skirt — two seams on either side. I could make a toga, which has only two seams and buttoned on the shoulder, and I could choose various widths depending on what cloths I had available or how much I could add into the pattern.

LMH: And then when you went back to New York you continued wearing them?

MM: That’s how I started because people photographed me in those clothes and that was my first collection for Henri Bendel. As time went by I started making other things, started playing with the silk and then started the Marii pleating. Then when I had my own factory I could do whatever I wanted, because I had some good technicians and I wasn’t restricted to what I could do in Africa. First came clothes and then jewelry — jewelry to go along with the clothes.

LMH: I was wondering what attracted you to the pleating in the first place — what made you want to produce this type of pleating?

MM: When you start off you usually choose the most inexpensive base fiber since you don’t have that much money, so China silk was selling at $4.50 — maybe even cheaper than that – when I started so I figured China silk would be my base fiber, just like Stephen Burrows used jersey as his base fiber because that was inexpensive. So I thought, “What can I do with China silk to make it look a little bit better?” I started hand painting it and then I had to figure out how to reproduce the hand painting, because in America to make one screen it cost something like $1,000. I went to South Korea, to Seoul, and there each screen was $5 or $10, so I could produce very attractive silk designs and then make them into very simple tunics — two seams, very simple because at that time you couldn’t afford to do anything very grand like I was able to do as time went by. Then I started quilting — first I painted, then I quilted the silk in a very narrow line – well, in the beginning it was a much larger quilt and it took, over a period of time, to get the thin quilt, which is interesting because it is done with foam inside that is so thin that you are actually quilting something in a very fine quilt that has some strength but it’s very flexible — and, of course, requires no maintenance. Then I decided to start pleating China silk, and whenever you pleat China silk the pleat does not hold. So when I started pleating China silk all the dresses opened, so I figured that I must find the silk that is a polyester that looks identical and is as light at China silk that I can pleat and that will be permanent. And that took a long time to find that fiber. I finally found it in Australia, and I sent it to Japan where I had it converted — that was the beginning of the Marii pleating. There was a long period of time with the Marii pleating where maybe we had 20-30 different types of pleating before it became a very refined technique and was very thick – looked almost as thick as a Fortuny, though it isn’t because it is flat. A Fortuny, which is using silk, is condensed — they would need to use more fabric to get the same amount as mine, but mine will never be as thick though it will be permanent — a Fortuny is not permanent.

LMH: It must have been a very interesting process to be going in between all of these different countries and developing something new. Did it feel exciting at the time?

MM: It was just a matter of trying to get a product that I could sell — that was the main problem. It took awhile to get it in order and to get it to be a good product, maybe four or five years to get it to the perfection that it became.

LMH: There is so much historical referencing in your designs but there is such a timeless appeal and a modernity to a lot of the shapes — did you feel you were designing for the moment? In the 1970s did you feel you were designing for a modern woman or did you feel that you were trying to make something more timeless?

MM: That’s a very complicated question. Each collection was based on an ancient civilization so if we take the Egyptian civilization or the Greek civilization, the shapes were classically Greek or Egyptian and also so were the textiles. So that shaped a lot of the clothes, but they are also classical shapes — what’s more classical than a Greek toga? Or what’s more classical than the Egyptian clothes? If you’ve seen them at the Met, they were not much different than what I was making in Africa – a seam here, a seam here and a place open for the neck.

LMH: Did you feel that you fit in with the New York design scene when you were working in the 70s, 80s and 90s? Or did you feel that you were your own separate thing?

MM: Well, my clothes certainly didn’t look like Bill Blass or Oscar — they certainly didn’t look like my peers. They had different ideas of what they wanted to make.

LMH: In the 1970s and 1980s there was a strong push towards designing for working women. Who did you feel you were designing for? Who was your ideal customer?

MM: Well, she had to be rich in order to wear the clothes so it was usually an affluent woman who travelled a lot, because none of the clothes ever required any pressing or maintenance, and who probably had some career. The basic purpose was that they would have no maintenance problems on any of the clothes, so they could get into a plane and never have to worry. For example, one time, in Florida one of the maids in the hotel picked up one of my Marii pleated dresses and she went downstairs to try to take the creases out and she came back to my client – she was apologizing as she was unable to take the pleats out. She tried all day!

LMH: Did you produce the really fantastic, beautiful pieces from the runway shows? I’m thinking of pieces like the wedding dress from the Russian collection (Fall/Winter 1997).

MM: Well, some things were not produced. Out of around 110 pieces in each collection I think we used to always narrow it down to about 40 or 50 different ones that went into production — maybe less, 30 sometimes.

LMH: You did home decorations as well. Did you prefer doing fashion or home? Or was it all just part of one larger approach to lifestyle?

MM: Home furnishings were based on the textiles of the collections, so it is all just one-design approach whether you are going to make it into a sheet, pillowcase, or comforter…

LMH: Did you ever use any of the pieces in your own places?

MM: Oh, of course, I only used them. They were prettier than everyone else’s, or at least I thought so, in my slightly biased opinion.

LMH: When you started doing jewelry, did you learn how to make it yourself or did you work with artisans?

MM: That’s a long process as well — I had to learn how to make it. The reason I started hand-forged brass dipped in 22-carat gold was because all the ancient jewelry from Egypt and Greece was all in gold. I wanted to copy or get an idea of what the pre-Columbian civilization, the Egyptian civilization, the Chinese civilization, the Greek, Romans were doing. It took me a long time to learn how to do it with several craftspeople to help.

LMH: And those hand-forged brass pieces were for your own collection?

MM: They were for production. Each collection usually got about twenty new pieces between earrings, bracelets… And then I did licenses where I did hundreds and thousands of jewels.

LMH: Do you miss designing? How have you spent your time since closing your company?

MM: No, I don’t. I have been everywhere in the world except the North and South Poles. I made a point to see the world.

It is Mary McFadden’s curiosity about the world and sense of adventure that helped her produce clothes that are completely unique. McFadden’s designs are a complete testament to her interests and passions — spellbindingly recreated in luxurious fabrics and ornate embellishments. Like her peers (Blass, Beene, de la Renta), McFadden’s work did reflect the world of the society women they were worn by, but hers also eschewed trends to instead be timeless evocations of other epochs and cultures filtered through the eyes of a thoroughly modern working woman.