Looking for the Real Fred Leighton: Part I

The Selling of Native American and Mexican Handicrafts in the early Twentieth Century

You’ve likely heard of Fred Leighton, whose antique and vintage gems sparkle on celebrities on red carpets and at the Academy Awards, or visited the elegant store on Madison and East Sixty-Sixth Street. Or you might have come across a Mexican wedding dress in a vintage store, bearing the legend “Fred Leighton” in swirling script. What do fine gemstones and Mexican garments have to do with each other? And who was this elusive Fred Leighton? When I first looked into this, I quickly discovered that the companies were one and the same, but that the “Fred Leighton” of antique jewelry fame was Murray Mondschein, who purchased the Mexican import company in the early 1960s, later adding jewels to his store’s merchandise and then taking the name as his own.

Eager to discover who the real “Fred Leighton” was, I fell down a rabbit hole that led me to traverse the history of twentieth-century Mexico and the American Southwest, exploring questions of cultural appropriation and appreciation, indigenous arts and their influence on fashion, tariffs and global economic troubles, among other topics.

Due to the length of this article, I’ve divided it into two parts - read part II here.

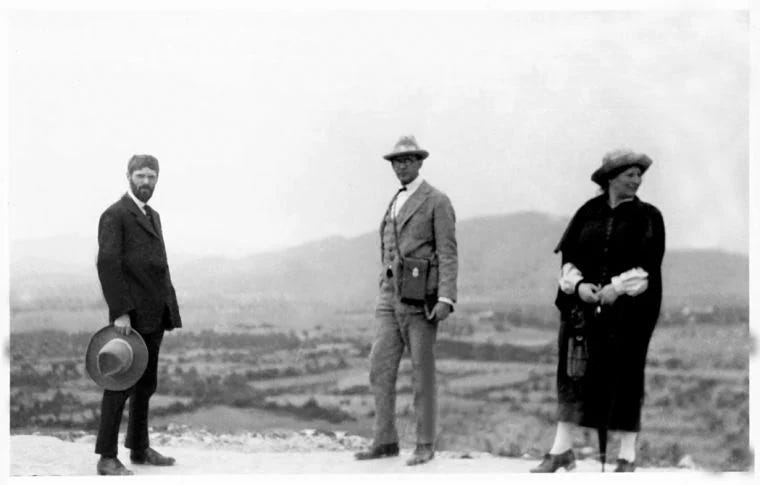

The original “Fred Leighton,” Frederic William Leighton, was born in 1895 in Chicago. In 1918, he registered for the draft in Chicago, with his draft card stating that he had “conscientious objection to any form of service on Christian grounds.” Soon after, Leighton moved to the southwest; it is unclear whether an interest in indigenous arts drew him there or if he developed one after his move. He appears to have spent his time going back and forth between New Mexico and Mexico, becoming quickly regarded as an expert on local native arts and crafts. In 1923, he wrote likely the first appraisal of Diego Rivera to be published in the United States, in the weekly news periodical The Freeman. With Taos and Mexico City becoming enclaves for European and American bohemians, Fred Leighton took on a role as their educator of American Indian and Mexican art; among those he encountered was the British author D. H. Lawrence, who Leighton helped introduce to Aztec myths and art, which Lawrence directly used in his 1926 novel, The Plumed Serpent. They traveled together a bit in Mexico City and Chapala, as referenced in his essay collection Mornings in Mexico, with poet Witter Brynner later recalling in Journey With Genius that Lawrence ordered Leighton out of his sight during one of his common rages. Around 1927, he returned to Chicago and opened the Indian Trading Post on North Michigan Avenue. According to the Chicago Tribune, the Indian Trading Post was “striving to stimulate the recent movement toward the use of American Indian motifs in home decoration.”

“Such a one is Fred Leighton, who has come from the Indian country of New Mexico to establish a unique shop in Chicago. This is the Indian trading post, fortunately situated on the site of the infant Chicago old Indian reservation, not far from the Chicago River where old Fort Dearborn stood when Chicago was a military outpost. On this site the Ottawa and Pottawattomie Indians traded furs for coffee, tobacco and sugar. Today, Indian goods of a different sort are marketed—Navajo blankets and rugs, baskets, pottery, jewelry.” – Buffalo Evening News, February 13, 1929

Leighton regularly appeared at social clubs around the city, giving talks on subjects like “American Indian Art and Its Useful Future” and “The Decorative Possibilities of Indian Handiwork,” while showing off some of the goods he collected and sold. Often a real “Indian” appeared with him—at one lecture, “Princess Ineima, a Hiawatha Indian, gave songs of Indian lore and interpreted them for the guests,” while at another, “B. Begay, the only Navajo Indian in Chicago,” appeared in tribal costume to sing “melodies from the famous ‘Squaw Dance.’” Considering there is no Hiawatha tribe—Hiawatha was an Onondaga leader and co-founder of the Iroquois Confederacy—it is hard to know who these “Indians” really were. As anthropologist Nancy J. Parezo has stated, “Every American knows what an American Indian should look like. It is general American popular culture knowledge. But what most Americans in the 1930s through the 1950s ‘knew’ was not reality, it was an iconic Indian seen through the lens of essentializing American stereotypes”—and those “essentializing American stereotypes” came from the work of white men like Fred Leighton, who through his store’s imagery, object selection, and educational talks cultivated a vision of Native Americans and their art that existed more in fantasy than reality.

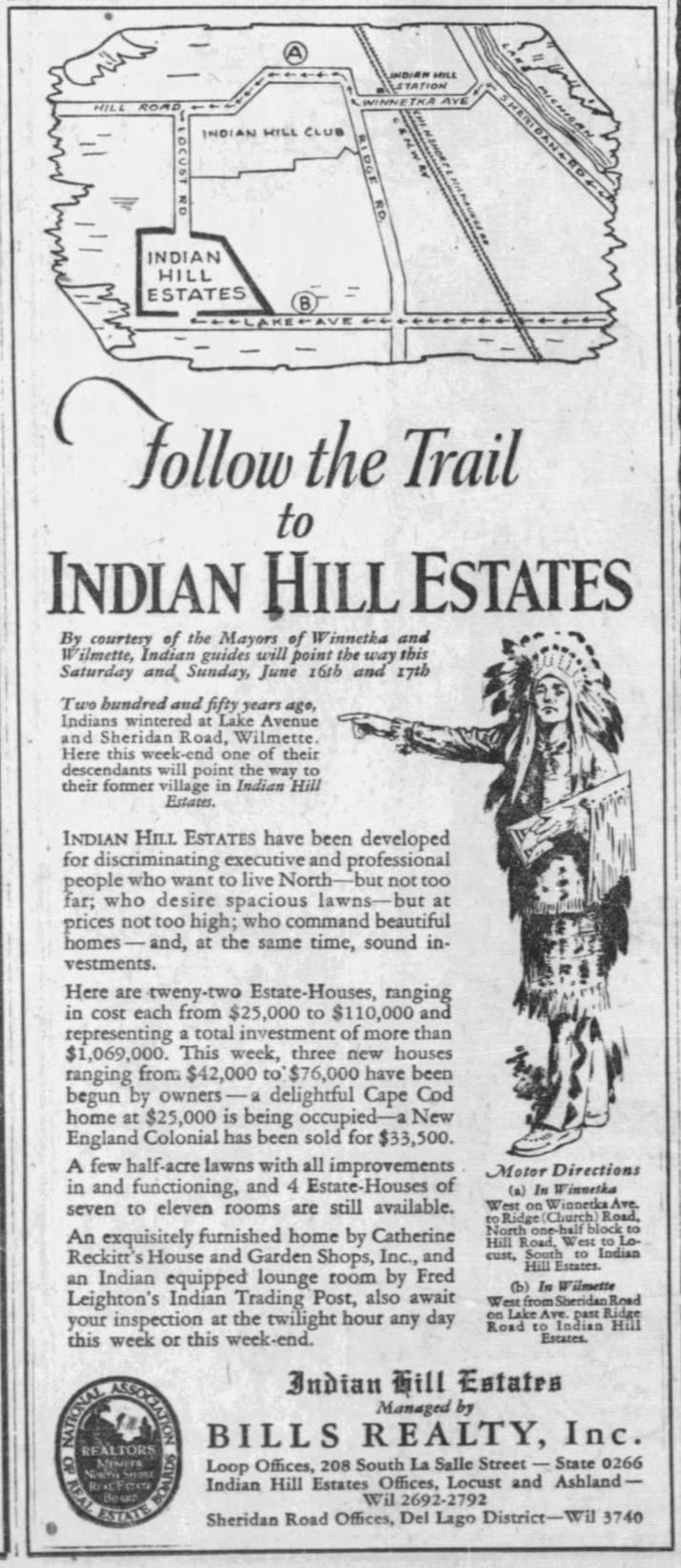

The languaging around Fred Leighton’s Indian Trading Post and his work is that of the exotic other, relying on stereotypes of indigenous peoples. When the Indian Hill Estates subdivision was built in Wilmette, outside Chicago, he was brought in to design an “Indian equipped lodge room” for all the “discriminating executive and professional people who want to live North.” The developers, Bill Realty, used tribal names for many of the streets, while the subdivision’s logo featured a Native American man with a Plains Indian feather headdress—the ads talked loosely about “Indians” wintering in the same location, but made no mention of the Potawatomi, Ojibwe and Odawa people who lived there (none of whom would have worn a warbonnet like the logo). Unsurprisingly, Bills Realty would want to further capitalize on their appropriation by bringing in “an expert” like Fred Leighton to lend some “authenticity” to their suburban fantasyland. For open houses, “Indian guides” were brought in to “point the way” to the estates. A surviving photo shows a group of Native American men in front of the Wilmette home of Ben Bills, one of the developers—a note on the back says they were in town to advertise Indian Hill Estates. They are all dressed in a hodgepodge of Native American garments and headdresses, likely all sourced from the Indian Trading Post, flattening the differences of individual tribes into a stereotype.

The Indian Trading Post operated both as a store and an exhibition space. In 1931, Eleanor Jewett reviewed one such show in the Chicago Tribune, leaning heavily into stereotypes of the uncultured savage: “There is black pottery by three Indian women, Romona, Susana, and Marie, striking bowls and jars which would make stunning lamps. Oqwa Pi is the Indian brave whose paintings are featured. These are thoroughly delightful. The coloring and drawing are refreshingly exact. You may read all kinds of legends in the symbolic pictures and in the others, those of costume and customs, you may read the life of an Indian village. Even today the Indians have a civilization untouched by the white man.” The objects on view were likely also for sale, to be purchased by white American families to add a touch of the exotic to newly built suburban homes. That year, Leighton also lent Navajo blankets to a booth curated by socialite and champion of Indigenous arts, Amelia Elizabeth White, on behalf of the Bureau of Indian Affairs at the Antiques Exposition at the Grand Central Palace in New York. Set up as a model living room reminiscent of “an early American colonial room,” White incorporated “antique American Indian textiles, pottery, baskets” to show “how Indian art objects may be used as interior decoration.”

“Indian”-inspired interior design was quite the fad in the early 1930s, as this mention in the Chicago Tribune illuminates:

“…Mrs. Thomas Woods Stevens is working with Fred Leighton of the Indian Trading post to introduce an ‘Indian’ room into every home, or an Indian roof, or an entire Indian cabin on every one's favorite fishing grounds, Mrs. Stevens has decorated a number of delightful Wisconsin cottages and the richness of the material at her disposal is surprising. There are lamps of Indian pottery, rugs of Indian weave, chairs, tables and benches of twisted wood and thin, beaten skins, lampshades of skins, and a beautiful variety of Indian ornaments and pictures with which to make walls beautiful. To appreciate the distinction and the merit of this Indian furniture and decoration the pieces must be seen. Primitive American art will find recognition among many who value sincerity and honesty in craft. And these things are good in themselves as well as good for the history they suggest.”

You can see some examples of extant Native American-inspired interior details in the Chicago area in this blog post.

While piecing together Fred Leighton’s life, I came across a PhD dissertation by Emily Schuchardt Navratil, “Native American Chic: The Marketing Of Native Americans In New York Between The World Wars,” that helped provide some further information on his expansion to New York. As Navratil shares, in 1930, Amelia Elizabeth White (the socialite and gallery owner he would later lend Navajo blankets to) explored a partnership with Leighton. Based on letters in the Martha & Amelia Elizabeth White Papers held at the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe, Navratil uncovered that Leighton approached the White sisters and Mary Cabot Wheelwright, “In hopes of expanding to New York, and eventually opening a nationwide chain of Indian shops”; the three women all agreed to put $10,000 each toward the project. In December 1930, Amelia Elizabeth White presented Leighton with a formal agreement to consolidate Ishauu [White’s gallery on Madison Avenue] with The Indian Trading Post, but two months later, “she withdrew the offer, citing a potential conflict of interest” with the Exposition of Indian Tribal Arts, a comprehensive exhibition of American indigenous arts she was helping to organize to open in late 1931. According to Navratil, “White felt that people might misunderstand their association and told Leighton that ‘such a misconstruction would certainly create an unpleasant impression in connection with your business and it might be disastrous to the Exposition. I have, therefore, decided that you had better count me out for the next year or two.’” The EITA went on to open to much acclaim that December, attracting over 13,000 New Yorkers to view almost six hundred objects, before touring the country under the auspices of the College Art Association.

Though the Indian Trading Post’s emphasis was primarily on Native American handicrafts, Fred Leighton’s longtime interest in Mexican arts and crafts continued. Several months after Diego Rivera’s groundbreaking exhibition of murals at the Museum of Modern Art (on view from December 22, 1931, to January 27, 1932), Fred Leighton held an exhibition of Rivera’s drawings and lithographs at his Chicago store, while he imported a small amount of Mexican goods.

Fred Leighton moved ahead with opening a New York store without Amelia Elizabeth White’s help. In late 1933, a friend of White’s wrote her to report that “Mr. Fred Leighton is opening a gallery of Indian art at the southwest corner of Fifth Avenue and Eighth Street. I do not know what the final title will be but I am going to watch him for infringements.” The following December, The Santa Fe New Mexican announced that Wick Miller, the owner of a trading post in San Ysidro, New Mexico, was now connected with “La Fiesta, a shop in New York, operated by Fred Leighton, which deals in southwestern and Mexican products.” My research turned up no further mentions of La Fiesta, while Miller appears to have returned to his own Post in New Mexico. Fred Leighton’s Indian Trading Post opened sometime in mid-to-late 1935 at 15 E. 8th Street, at the heart of bohemian Greenwich Village. Journalist Helen Worden described it as “a fascinating little shop, up one flight of stairs, in an old brownstone front house…” There she met Mofsie, a Hopi Indian shop assistant, who explained that the store mainly sold “to foreigners. The English and French tourists like to buy Indian things to take home. That is their idea of America!”

With the Chicago store closing sometime in the 1930s, Leighton’s focus was now completely on the New York store. Sometime around 1940, he married a “blonde, pictorial” woman alternately called Juanita or Jane by the press; I was unable to find their marriage license or any more details about her, so I do not know if she was Mexican or if “Juanita” was an appropriated nickname. Perhaps emboldened by his wife’s apparent fascination or knowledge of Mexico, Leighton began filling the NYC shop with an ever-increasing array of Mexican goods—leading to a renaming, Fred Leighton’s Mexican Imports. The couple purchased an old adobe house in Guadalajara, Mexico, which they used as their base for eight months of the year; using that time to scavenge around the country, collecting antiques and meeting artisans. This came at a time when there was a soaring interest in Mexican and Latin American handicrafts, which Leighton was quick to capitalize on. In 1939, Leighton began advertising huaraches in such opposing periodicals as the communist newspaper The Daily Worker and Vogue, while Vogue also suggested visiting the store to pick up a “real Mexican money belt” to pair with country tweeds.

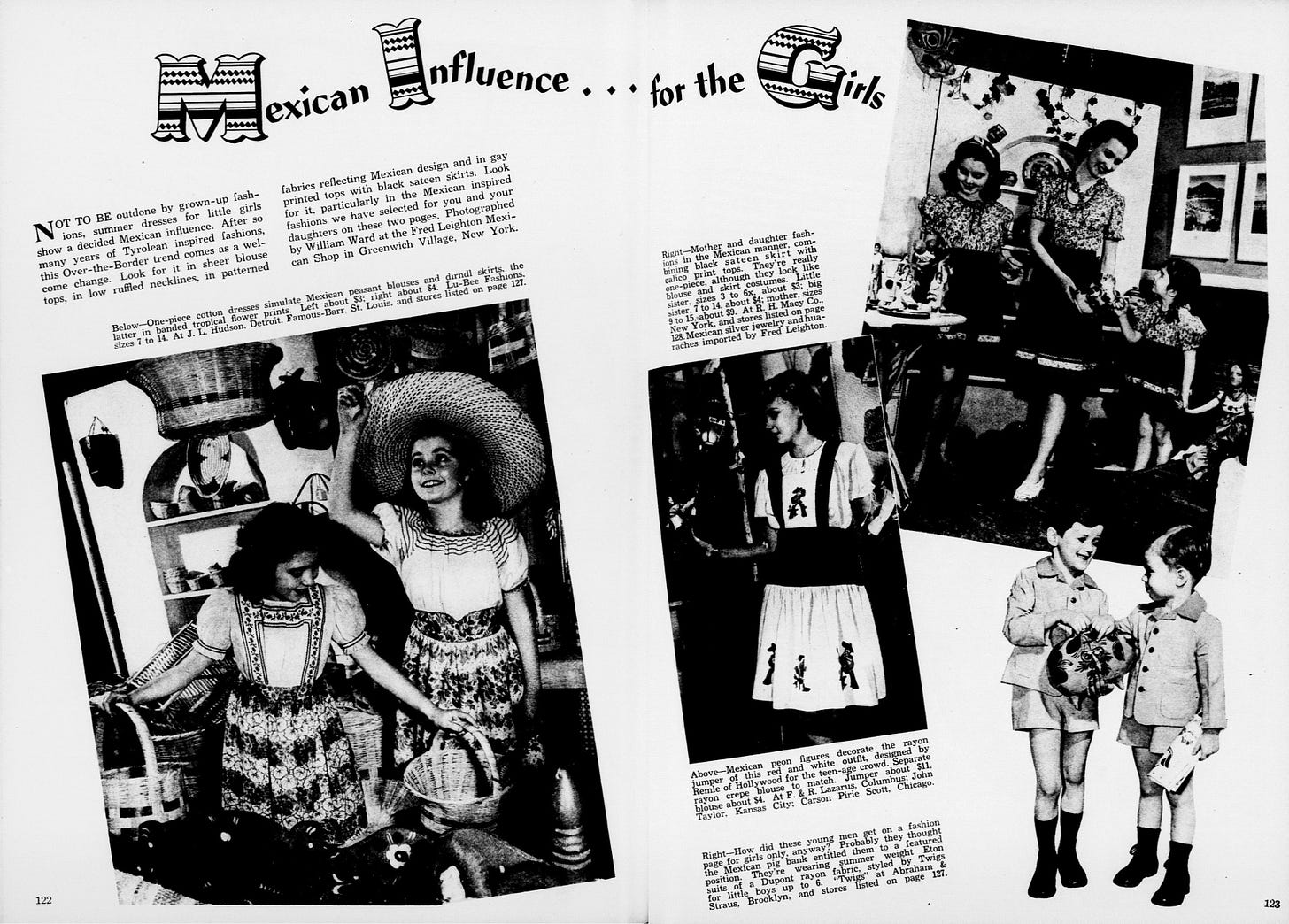

As shops like Fred Leighton imported more Mexican home goods to New York and the United States, soon followed the interior designers and journalists set on turning “Mexicana” into the latest decorating craze. Newspapers and magazines highlighted the use of Mexican tin around the home, with Vogue recommending the use of tin reliquaries as flower displays for garden parties while describing tin trays and pitchers as “exactly The Thing for lunch on the terrace.” The New York Times suggested that “huge tin tankards, more than two feet high, and slender, look fine used as vases for brilliant Fall flowers,” though they explained that the shop showed them “full of pine branches and flowers made of pine cones.” The appeal of tinware was in its “simple, effective patterns… [that were] quite inexpensive and dressy at the same time.” There was more to Mexican décor than just tinwork—as The New York Times explained, “Mexican design is highly prolific, and produces no end of good things…” before going on to advocate for Mexican hand-painted furniture. Cleverly, Leighton rearranged the store into a series of model rooms to delight and inspire visitors and shoppers. For example, a small study was painted yellow with a brown dado and hung with some “dark red curtains [that] are really made of a serape, or Mexican blanket-cloak, slit down the center, where the two woven strips are sewed together.” It was decorated with a “Navajo rug, split cedar sapling chairs and a settee covered with pigskin…” Mexican chairs, headboard and antique chest, painted white with flowers, brightened up an olive-green bedroom. As new goods came in, the rooms were reset, providing a continual source of decorating ideas, as well as an ideal location for any magazine photoshoots highlighting Latin American or Mexican goods or people; Town & Country and Parents’ Magazine were among the publications that photographed editorials there in the 1940s.

Once the United States entered WWII, Leighton’s ads were quick to single out the products the store had available that were made from unrationed materials. An ad published in Vogue announced that for $2.50 a pair, one could buy “ALPARGATAS—A grand new shoe style (NOT RATIONED)—Here's foot comfort de luxe—a modification of the Basque or Spanish Espadrille new and gay with colored hemp soles. Ideal for slacks, sports or lounging made by hand in Mexico.” Another advertisement offered Mexican dolls as an alternative to the paper dolls often suggested to replace rationed baby dolls. Keen to reinforce the importance of trade with Central and Latin America during this time of instability, Fred Leighton was elected to the executive committee of the Latin-American section of the New York Board of Trade in 1943; two years later, he was also named to the Department of Commerce’s Office of International Trade’s Export Advisory Committee.

Looking for the Real Fred Leighton: Part II

This is the final part of a two-part article on the importer and retailer Fred Leighton. To read part one, click here.