Le Drugstore: A Parisian take on America

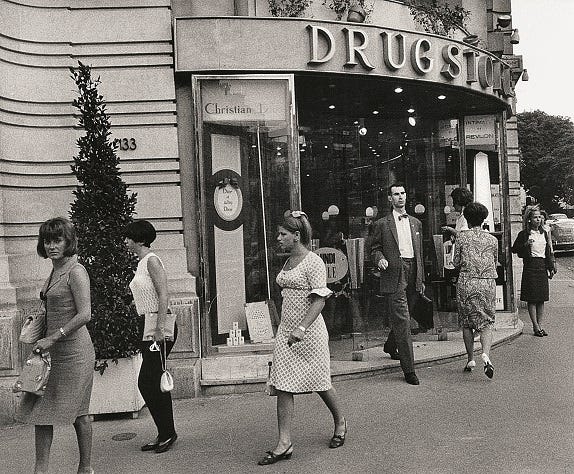

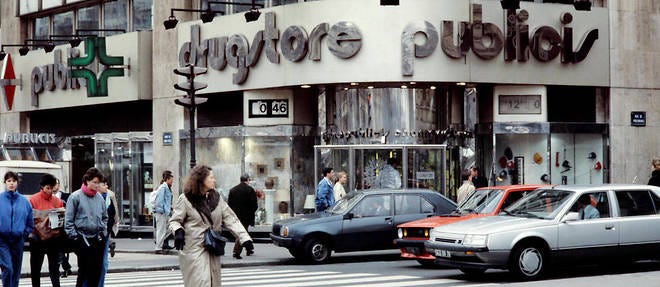

When a classic American-style drugstore—complete with a soda fountain and lunch counter—first opened in Paris in 1958, it was quite immediately declared the hippest place in town. Located on the corner of the Champs-Élysées and Rue de Presbourg, a block from the Arc de Triomphe, Le Drugstore (also called Drugstore Publicis) was an immense tribute to American consumerism and cuisine. Marcel Bleustein-Blanchet, French advertising maestro and founder of the Publicis agency, had recently returned to Paris after a period working on Madison Avenue. Captivated by “the city that never sleeps,” he wanted to bring some of that 24/7 energy to Paris. He discovered this concept one evening at midnight, in Manhattan in 1949: “I saw the light of a small shop (a drugstore ). I went in to ask for directions. In two minutes, I was able to buy a hamburger, a toothbrush, a newspaper and a pack of cigarettes. To get the same thing in Paris, I would have had to find a tobacconist, go into a café and give up the toothbrush, for lack of an open pharmacy…” He purchased the Hotel Astoria for several million dollars, locating the headquarters of his agency on the upper floors, while on ground level Bleustein-Blanchet sought to create a place that would “cater to a full-spectrum of consumer self-indulgence”—shopping, drinking, eating, music—bringing American convenience and bar culture to the Parisian public.

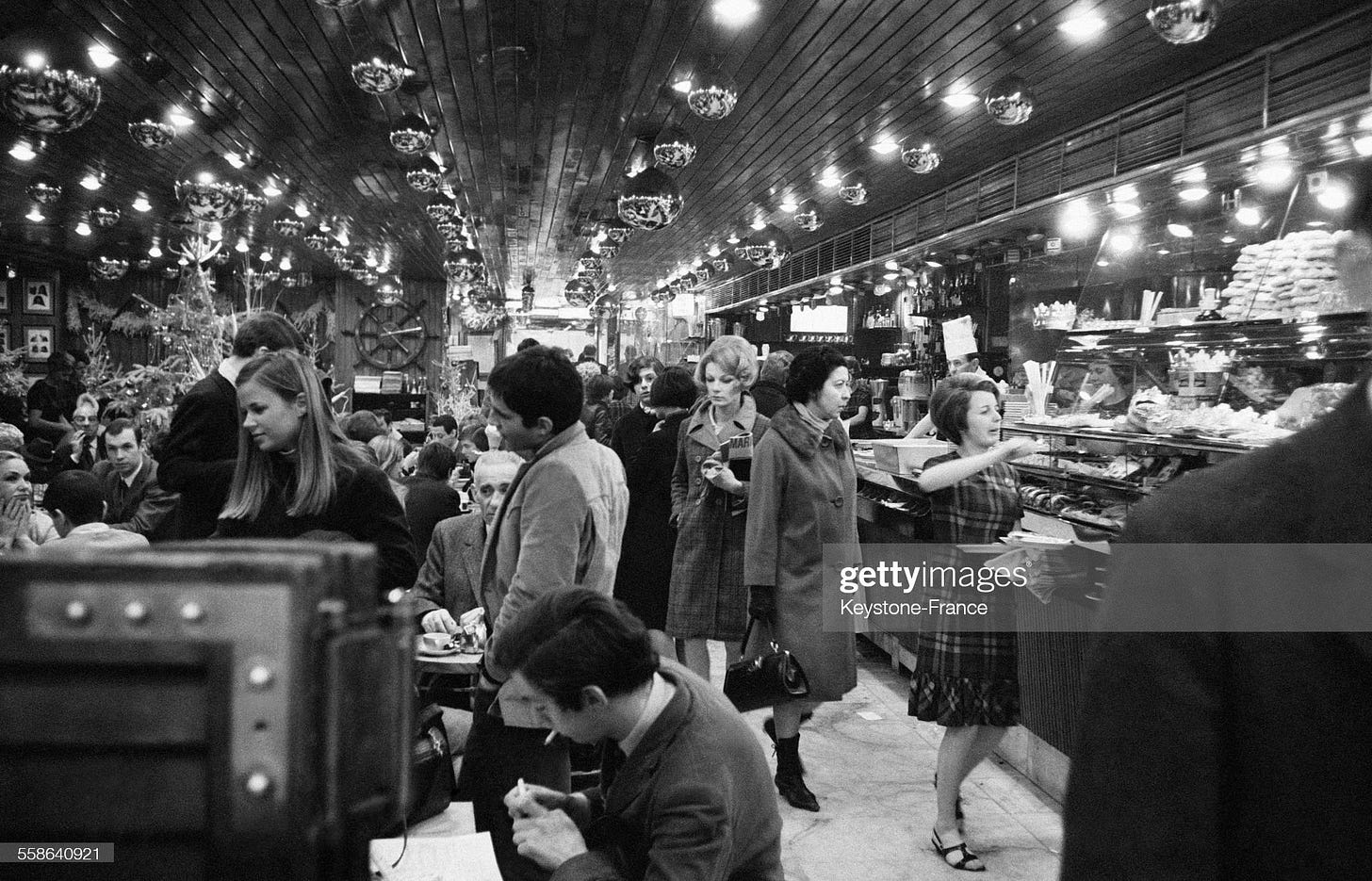

As the doyenne of American fashion journalism, Eugenia Sheppard, wrote: “The Paris strip tease joints, the night clubs with sobbing violins, even the quaint little bistros were cleaned out of French customers this summer and left completely to the tourists. All these jolly little night spots have acquired a formidable rival, as far as the Parisians are concerned.” Those Parisians weren’t coming there to visit the front counters that sold “everything from French perfumes and silk scarfs by top Paris designers to dirty corkscrews and ashtrays shaped like Notre Dame”—instead they frequented the rear restaurant, Le Pullman, a paean to the American Pullman train dining cars. This “chic, new place to drop in late at night” featured “tables decorated with paper napkins and ketchup bottles,” surrounded by “walls of a blond wood that is next door to a knotty pine” and decorated with guns and wagon wheels. “A cavalcade of Americana,” the Los Angeles Times reported that it's interior mixed up “scenery from The Shooting of Dan McGrew with elements of the Stork Club, the Civil War, and a general store in Nebraska.” Parisians came here to feast on hot dogs and hamburgers, “such exotic Americanisms as cream of tomato soup with crackers, bacon-and-tomato-on-toast, chile con carne and avocado salad,” or raw shellfish in the adjacent oyster bar.

Towards the front was a soda fountain, where “from dawn until next dawn, you’ll find eight to 20 young replicas of Brigitte Bardot lined up… having Les Bananes Slit of Les Coupes de Trois Parfums (strawberry, vanilla and chocolate)”—likely hoping to be discovered à la the famous tale of Lana Turner and Schwab’s Drug Store. Somewhere between the popcorn machine, shoe-shiner, and oxygen machine (only 50 francs for pure air), was an actual pharmacy, but few of the customers who filled Le Drugstore until two thirty in the morning came for that. Late at night, it was frequented by post-work strippers, but during the day it was popular with people of all ages who had “learned the advantages of a quick snack that leaves time for shopping in the lunch hour or fits in before or after the theater.” Speed not generally being something Parisian cafes or bistros were known for, the success of Le Drugstore’s quick meals resulted in the opening of many le snack (snack bar) and le self (cafeteria).

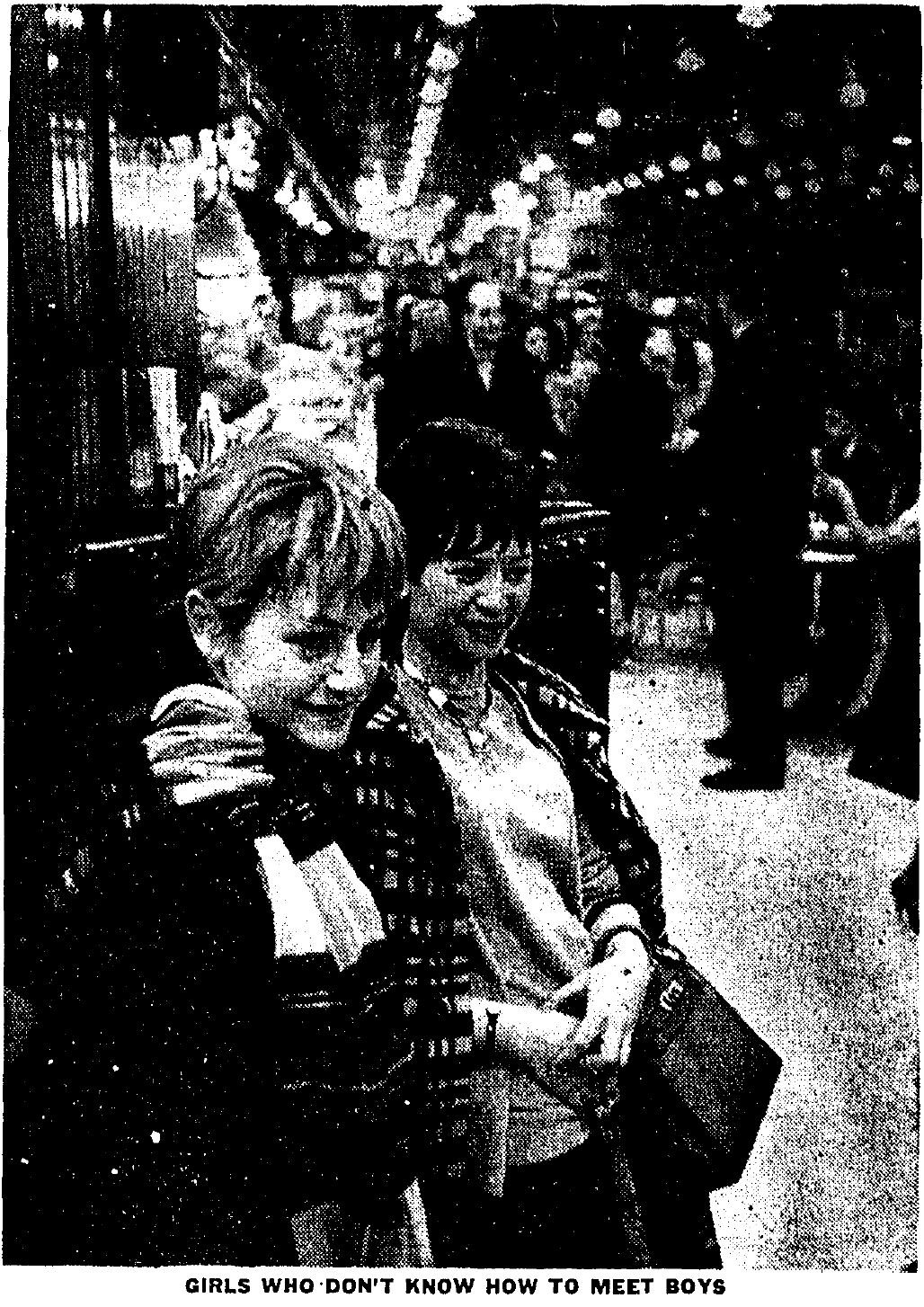

By 1961, Le Drugstore was swamped with one particular age group—teenagers. Often up to as many as 250 at a time crowded the space after school, reading magazines for free and ogling the opposite sex. “They’re a nuisance,” a soda counterman complained to the New York Herald Tribune. “They don’t buy anything and when they order a milkshake they expect to nurse it all afternoon. We chase them away but they keep coming back, like pigeons.” Of course, this kind of anti-teenage sentiment was common in the American media since the mid-1950s so along with exporting rock ‘n’ roll, hamburgers, milkshakes, and teenagers to France, the US also exported adult anger at teenagers. It was the place to see and be seen, to check out boys and girls, maybe make a date to go to one of the new American-style bowling alleys that had recently opened. Even a plastic bomb going off there during the summer of 1961 (luckily twenty minutes after closing) seemed to have much effect on its popularity.

Stories about the teenage Le Drugstore fans spread far and wide, even making it into syndicated fashion gossip columns—in the “Latest from Paris” in August 1964, Monique shares: “Paris teen-agers divide sharply in habits and dress between the ‘Drugs’ and the ‘Golfs.’ The first category are the more sophisticated kids who stake out at ‘Le Drugstore’ – the bright new coffee bar giftshop, pharmacy and bookstore on the Champs Elysees. The other are ‘surf’ and ‘slop’ fans from a pop dance hall in the commercial section of town, called ‘Le Golf Drouot’ because it was once a miniature indoor golf course. ‘Golf’ girls wouldn’t dream of venturing out without swelling and teasing their hair-dos into the bulky volumes considered outdated elsewhere – and especially by the ‘Drugs’ whose hair is straight, flat, and brushed glossy. The girls around the ‘Drugstore’ love Chanel suits, skinny sweaters, and military style ‘riding’ topcoats with brass buttons, martingales and shoulder tabs. But the standard uniform for the ‘Golfs’ is a neat schoolmistress shirt blouse – usually worn with a man’s tie pin thru the points of the collar. For more dressy occasions, they add little-girl collars with a fine edging of lace, or white jabots on a finely checked or striped blouse.”

“…everything from America excites the truly young, and this is the reason for admiration of American painting, literature, theater, ballet and films among the creative. It may also be why it is chic to admire J.F.K., or the practical aspects of le drugstore, or American folk songs or Early American furniture (sold on the Champs-Élysées ‘imported from the U.S.A.’). Even the existentialists, who drank anti-Americanism with their nurses’ milk, prefer American styles, drinks, informality.” – New York Times, November 28, 1965

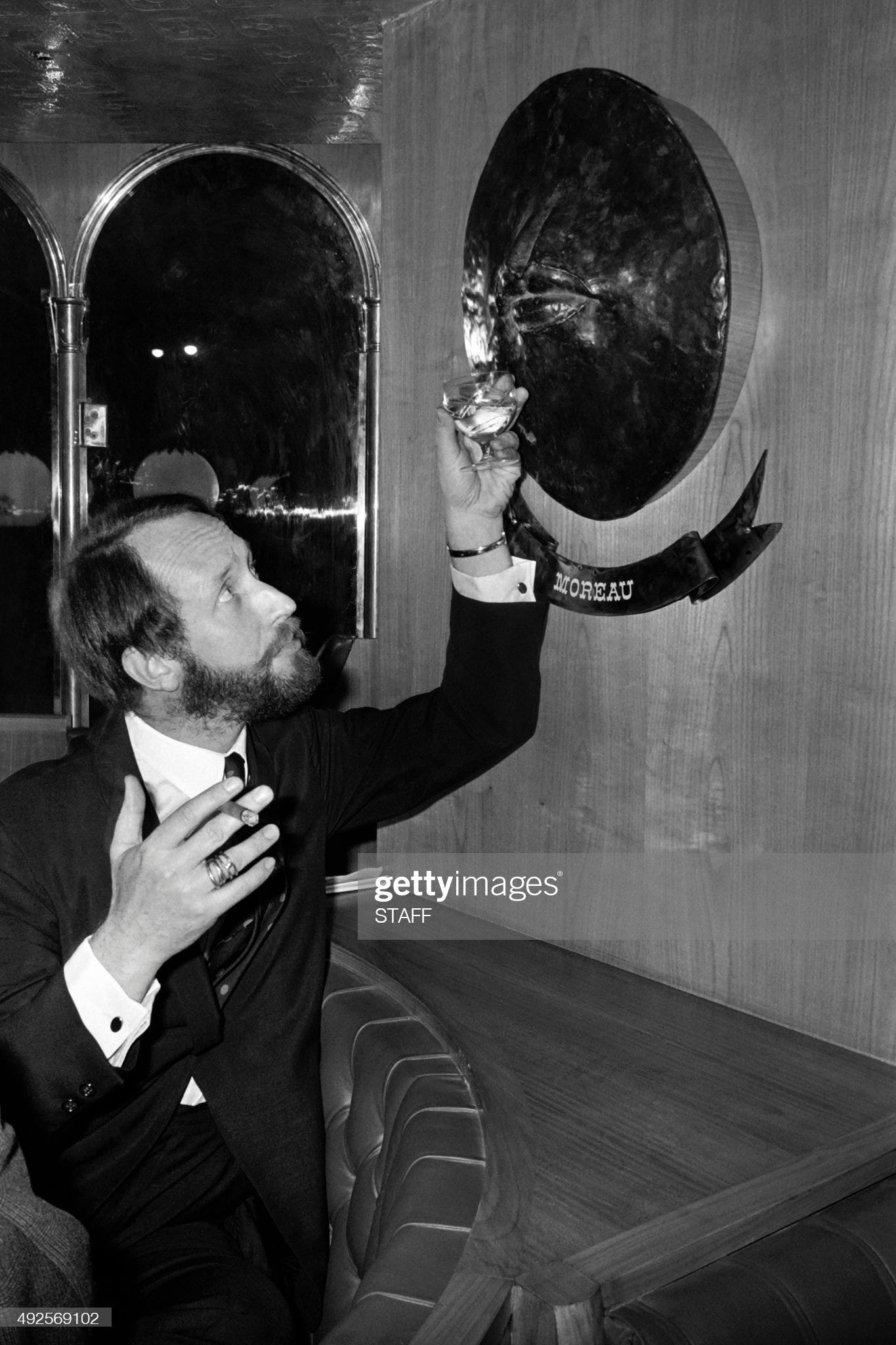

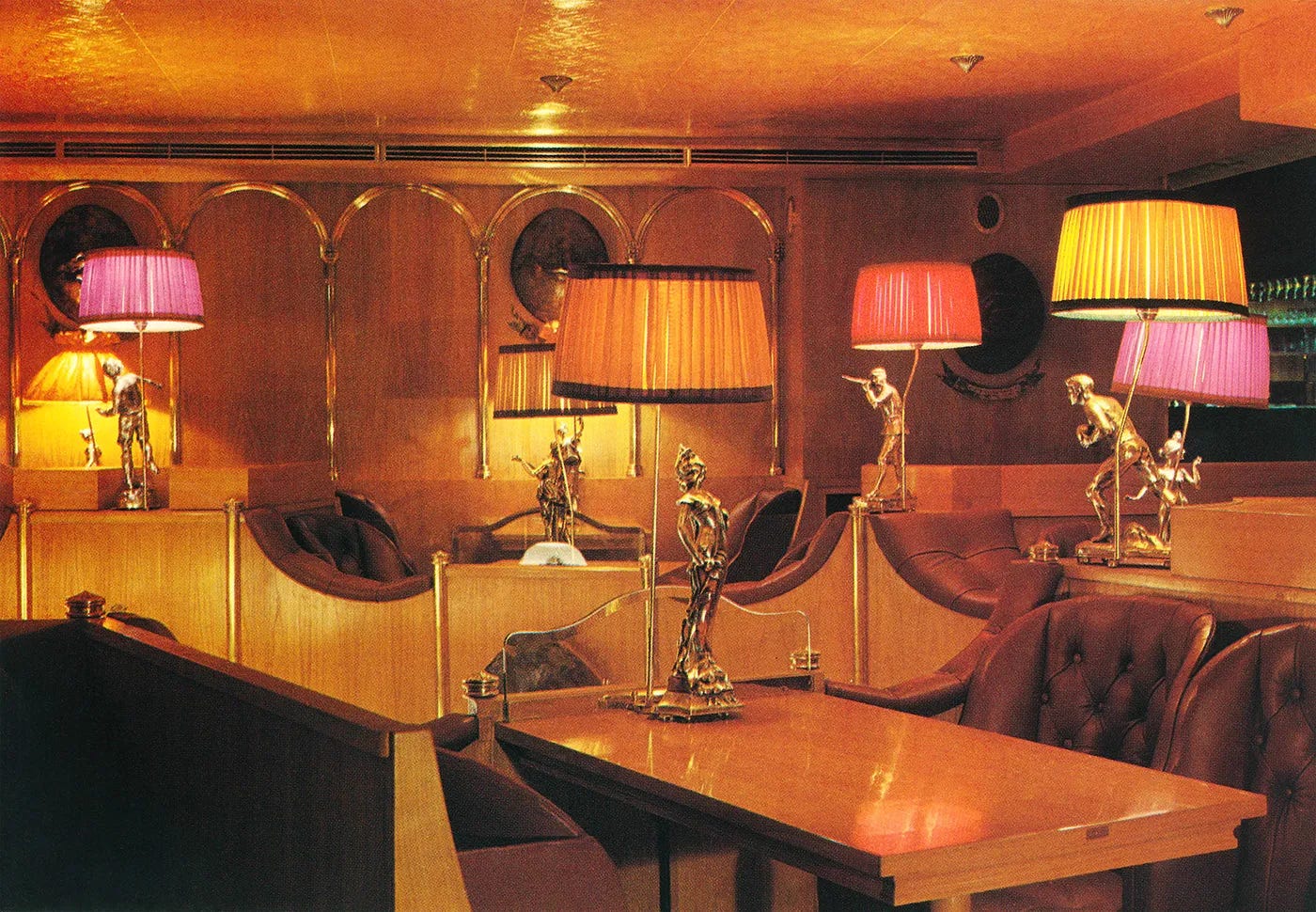

When the owners of Le Drugstore decided to expand to the Left Bank, there was much hue-and-cry over the location—taking over the space of Café Royal, a traditional French restaurant in the heart of Saint-Germain des Prés, next to Brasserie Lipp and directly across the boulevard from the main existentialist hangouts, Les Deux Magots and Café de Flore (all still existent). The second Le Drugstore opened on October 20, 1965, complete with a black-tie party for over 5,000 guests. Both locations were marked by the modernity of their facades and décor—glass, chrome, brass, glossy wood. Putting a new spin on the traditional bistro design of their rivals, for Saint-Germain Slavik created a “brassy décor which caricatures the Belle Epoque”—“all tones of brown with surrealistic touches (bronze reliefs of Moreau’s and Bardot’s lips, Picasso’s and Belmondo’s hands) ranged around the open dome in the center of the ground floor.” Declared by many to be the most hideous place in Paris, it was described by Le Monde as “Byzantino-1900” and the New York Times as “fraudulent fin de siècle”—these negative reviews did little to keep away the crowds.

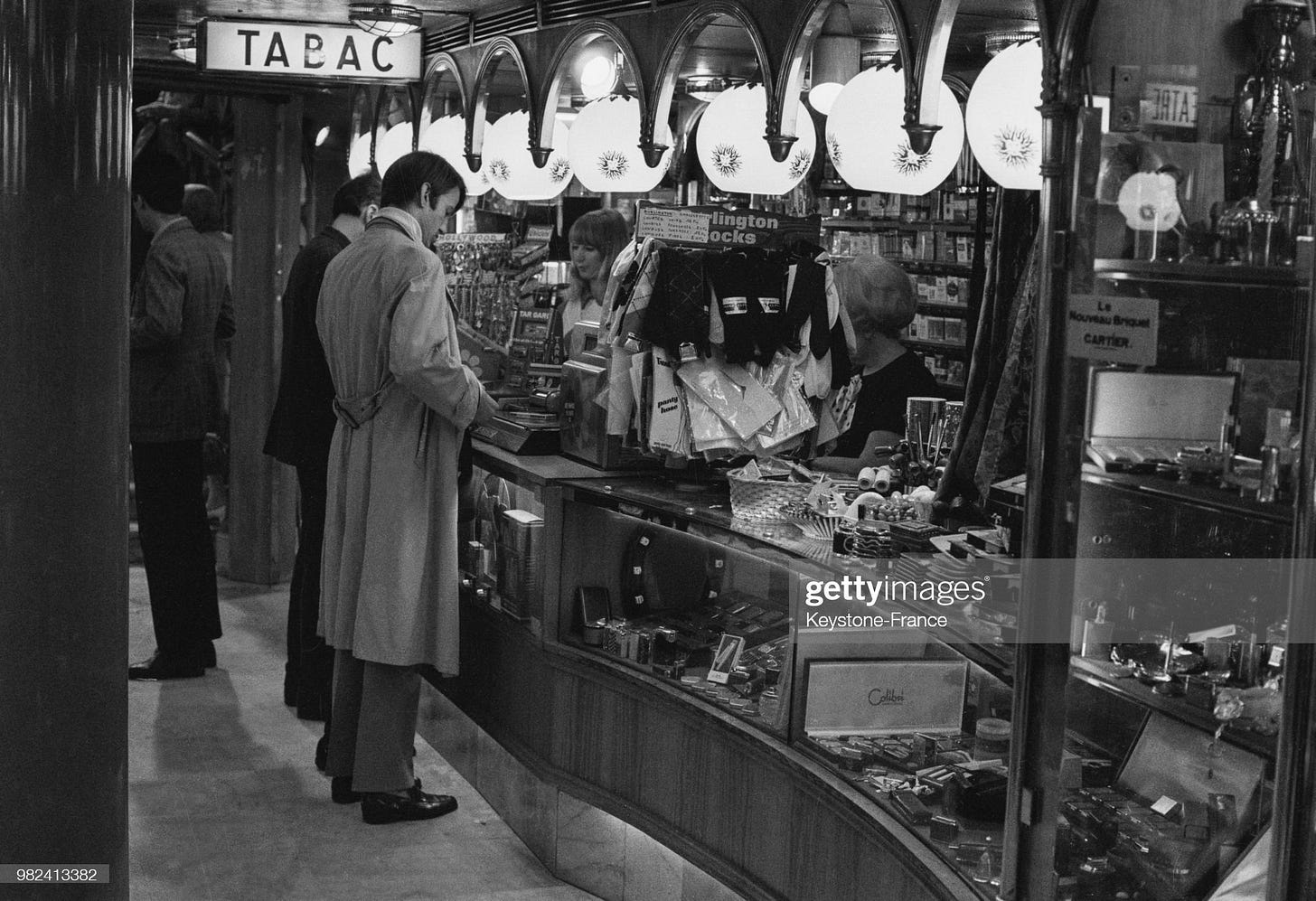

The restaurant was arranged around the dome center on the upper level, while below ground level was a 320-seat movie theatre—there was even supposedly a private theatre that directly connected to Brasserie Lipp. According to the designer Slavik (Wiatscheslav Vassiliev), Le Drugstore acted like a pinball machine for its visitors; the customer was"like a ball catapulted from one plot to another, he will be thrown from the bar to the bookstore, from the bookstore to the gift shop, from this here to the perfumery, then to tobacco, from tobacco to the cinema, from the cinema to another bar, from there to the restaurant or the picnic store.”

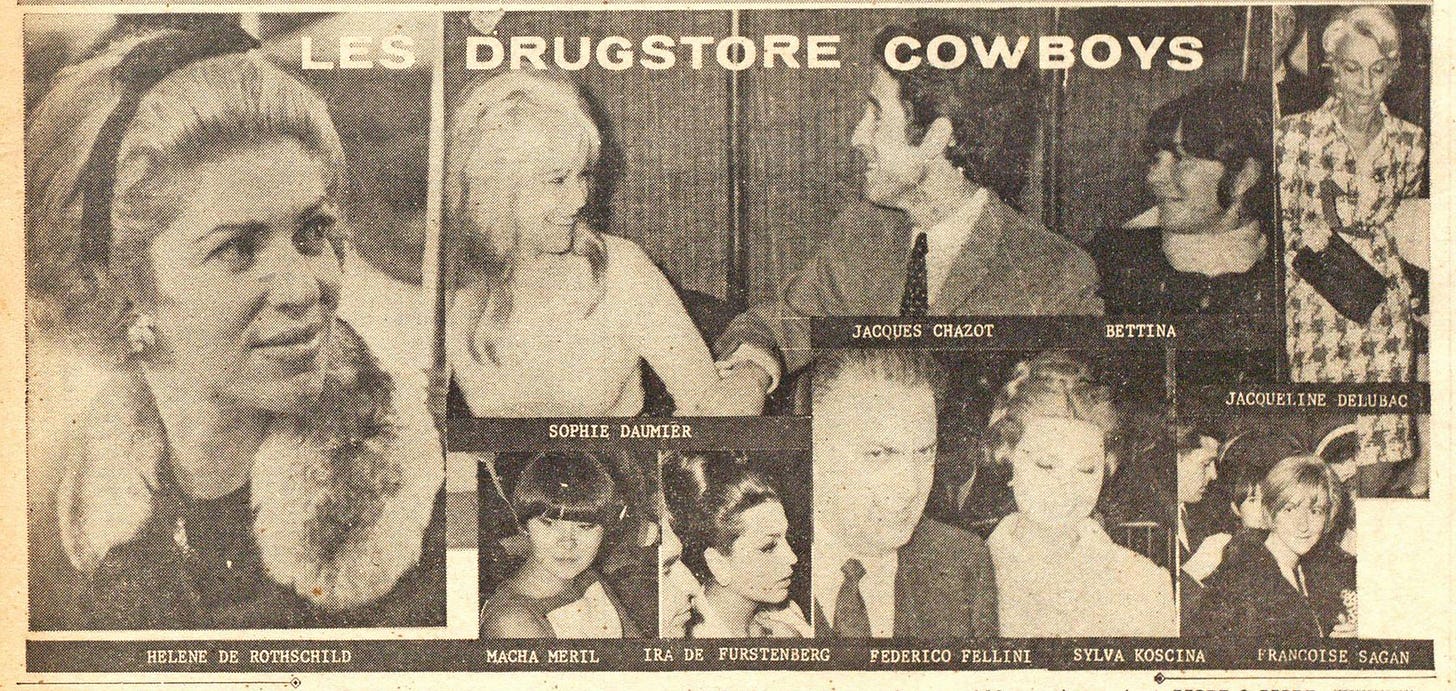

As much as a place to see and be seen as the original, two days after its opening Fellini premiered his new film Juliet of the Spirits for a crowd that included Francoise Sagan, Helene de Rothschild, and Princess Ira von Furstenberg. It wasn’t all fun and parties though—less than a week later, Moroccan politician and anti-colonial nationalist Medhi Ben Barka was kidnapped in front of the second Le Drugstore at noon on October 29, 1965; his body has never been recovered. In 1972 Yves Boisset released L'Attentat, a political thriller inspired by the kidnapping-assassination; scenes were filmed inside the original store (see below) and outside the Saint-Germain location.

The popularity of this Parisian spin on American drugstores led to the opening of replicas in cities across Europe—from London (the Chelsea Drugstore, also designed by Slavik) to Barcelona (“El Drugstore”) and beyond—and even back to America (more on that next time). Le Drugstore copies opened all across Paris and the suburbs—not connected with Bleustein-Blanchet, they took vaguely American-sounding names like “The Village” and sought to replicate and finesse his exceedingly successful template. Bleustein-Blanchet and Publicis opened a further two locations in 1970, and by that year, there were said to be fifty American-style drugstores in Paris and its environs.

A fire broke out at the Champs-Élysées location in September 1972; one person was killed and 300 people were evacuated. Both Le Drugstore and Publicis’ offices were badly damaged, with Bleustein-Blanchet’s art collection and small Eisenhower museum (he had been a sergeant with the Free French Air Force and on a liaison team with General Eisenhower at the time of the Normandy landing) destroyed. The fire was declared to be arson. Bleustein-Blanchet had hoped to keep the original façade, but it was declared unsafe. Pierre Dufau was chosen to redesign the space.

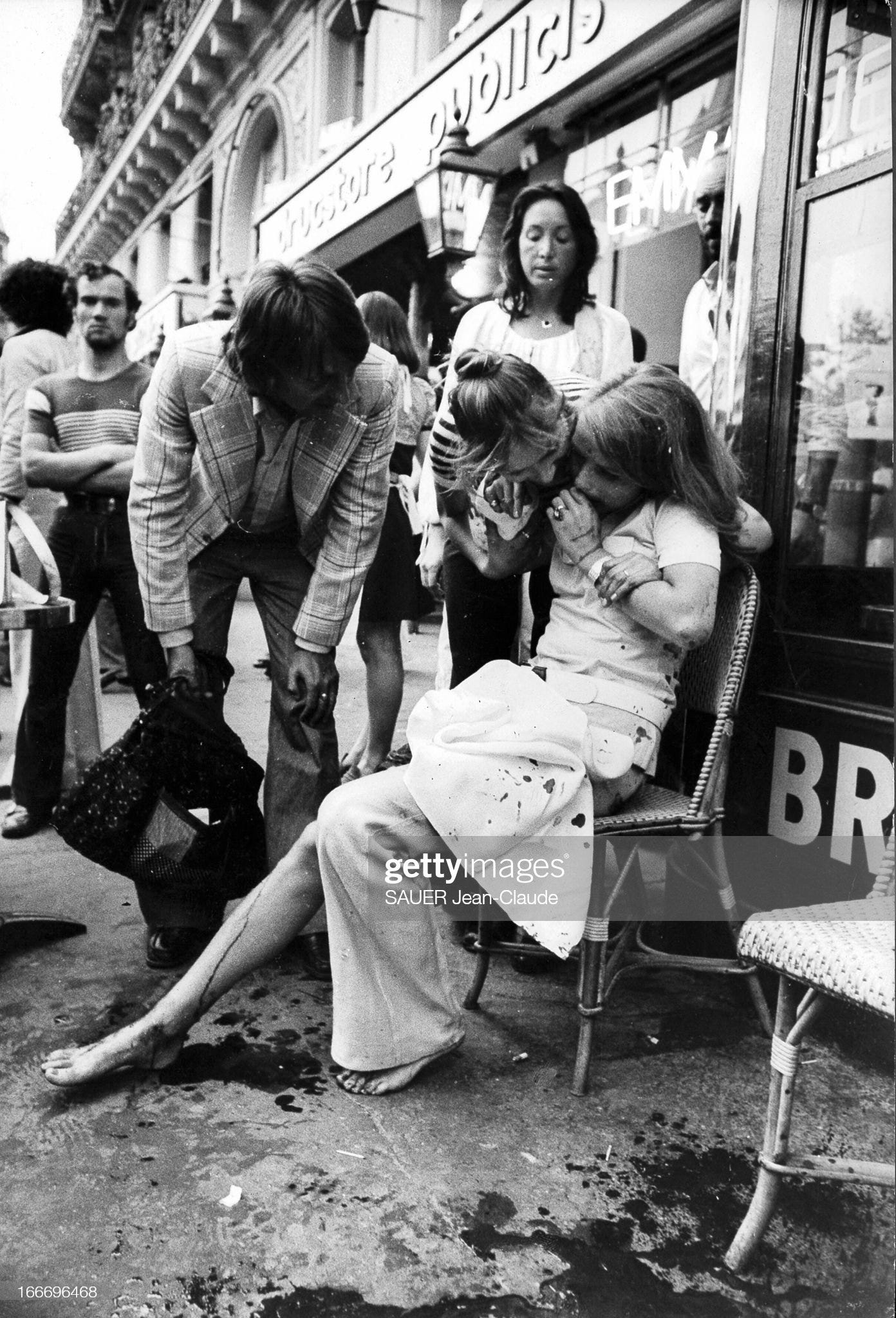

While renovations were still underway there, on September 15, 1974, a grenade was thrown from the mezzanine level of the Saint-Germain-des-Pres Le Drugstore down onto the shopping floor below. Two people were killed and thirty were injured. Three months later, both locations reopened—the Champs-Élysées drugstore having undergone a full reconstruction, now six floors of all glass punctuated with immense pilasters of Pierre de Souppes brown travertine. More than forty years later, in 2017 the notorious political terrorist “Carlos the Jackal” (Ilich Ramirez Sanchez) was tried and given his third life sentence for the attack, though he always denied any involvement.

Any anti-American, anti-modernity sentiment that had been leveled at Le Drugstore when it opened on the Champs-Élysées and in Saint-Germain-des-Pres was long gone by the mid-70s. Over decades, Le Drugstore had established itself as an essential part of Parisian life—so much so that there was an outcry when the Boulevard Saint-Germain location closed in 1995 and became an Emporio Armani boutique. The original location remains, though it has undergone numerous renovations since its 1960s and 70s heyday. In 2004, Italian architect Michele Saee attached Frank Gehry-esque curved glass panels to the façade. After a two-year closure for renovation, Publicis Drugstore reopened in 2017 with a complete overhaul designed by Tom Dixon with a single proviso: "reinventing the drugstore as it was in the 1960s". Dixon didn’t look to recreate the original saloon-inspired décor of the restaurant, but instead the more luxe side of modernism; Dixon’s website declares that the “timber walls and unique marble bars are complimented by deep tones of oxblood upholstery and brass fixtures that combine to make a contemporary nod to the glamour and sophistication of the 1960’s world of advertising.”

Over sixty-five years, Le Drugstore has gone from a celebration of American consumerism to a French institution to an elegant dining spot—by way of teenagers, milkshakes, and terrorism.

I am Slavik woman and carried out after his death the project of a book about his work which was completed in novembre 2021 : SLAVIK LES ANNÉES DRUGSTORE

BRAVO FOR YOUR ARTICLE AND THANK YOU FOR HIM !

I love this, thank you so much!