“I saw the birth as being a wonderful way to start the movie.” – Joyce Chopra

While I have no plans on turning the subject of this newsletter to pregnancy and motherhood very often, one documentary has been much on my mind since I found out I was pregnant. Last June I was supposed to interview the director and screenwriter Joyce Chopra for my podcast, Sighs and Whispers, but a health issue led her to postpone it indefinitely. As I was prepping for that interview, I rewatched her documentaries and films—the first of which is Joyce at 34, a 1973 documentary co-scripted with Claudia Weill (who later went on to make the very influential Girlfriends). Taking as their subject the birth of Chopra’s first (and only) child and her subsequent attempts to make sense of balancing motherhood and career, it was truly the first of its kind—a very female look at a very female problem.

Originally from Brooklyn, Chopra studied comparative literature at Brandeis, becoming interested in cinema while on a year abroad in Paris. After graduating, she attended theatre school in New York but found living at home with her family in Brighton Beach too difficult. Returning to the Boston area, Chopra and her friend Paula Kelley decided to open a European-style coffee shop in Harvard Square in 1958. Joyce invited local musicians, mostly jazz and blues to start, to play; within a few years, Club 47 was the center of the nascent folk music movement—a teenage Joan Baez got her start there. The documentary, For the Love of Music, explores the rich history of Club 47. On the quiet Monday nights, Chopra started programming old and rare movies—watching not for fun but as an education about cinematography, pacing, editing. She moved to New York, eager to get into the movie and TV industry, but found it closed to women: “They always asked me if I could type. If I could type then I could be a secretary and then maybe some producer would notice me and then perhaps I could be a production assistant. The fact that I didn’t want to be a production assistant was irrelevant.” Sent to visit the new collective Drew Associates—which brought together groundbreaking documentarians Robert Drew, Richard Leacock, D.A. Pennebaker, Terence Macartney-Filgate, and Albert Maysles—Chopra soon found her place working as an apprentice on the cutting edge of direct cinema. There she learned to edit, record sound, and film—only leaving NYC and returning to Cambridge after ABC TV completely re-cut a film she had worked on, changing the whole tenor of the piece.

Following the making of her first solo documentary film, The Wild Ones, Chopra was connected with the writer Tom Cole to work on adapting one of his stories for film. While that project did not come to be, the two fell in love—after much strife, leaving their respective partners and marrying in 1969. While working on the script for another film in London, Joyce found out she was pregnant at 33, then considered elderly for a first-time mother. “That film dominated our lives for a year and a half,” Joyce told the Boston Globe in 1976. “We made it because when I was eight months pregnant a friend called and said I should make a film about my relationship with my mother now that I was going to be a mother... I knew enough about filming to know that there were enough events in my life to provide material for it, and I was sure my mother would be wonderful on film.” Chopra was as much informed by the political and social currents of the time: “It was also because the women’s movement was making me look at the lives of women, and if you look at the lives of women, you have to look at the personal lives because that’s where most of them are. Many men don’t understand how important this is.”

From her 2022 memoir, Lady Director:

With the first exhilarating kick at five months, I'd had to admit to a lurking fear that had been growing inside me along with the baby. I worried that I would be irretrievably swept away into motherhood, as had happened to many women I knew, and that "Joyce the filmmaker" would cease to exist the second the baby was born. I got the idea, perhaps a bit crazy, that the only way I could prevent that erasure was to be contractually obligated to produce a film right after giving birth; I would then be "Joyce the filmmaker who happens to be a mother." When the offer to direct a documentary about an experimental school in Brooklyn suddenly came my way in my eighth month, I grabbed hold as if it were a life preserver.

I was telling my friend Barbara Norfleet, a sociologist teaching at Harvard, about the job I had just signed a contract for when she interrupted me with "Forget that . . . Why don't you do a film about whether a woman's relationship with her mother changes when she has a baby of her own? You're in a unique position to document this. Use yourself and Tillie as the test subjects." To which I immediately replied, "You have got to be kidding. That would be the most narcissistic... " I don't think I even finished the sentence. Until then, documentary films took as their subject notable public events or famous people, and the thought of producing a film about a woman having a baby seemed outlandish.

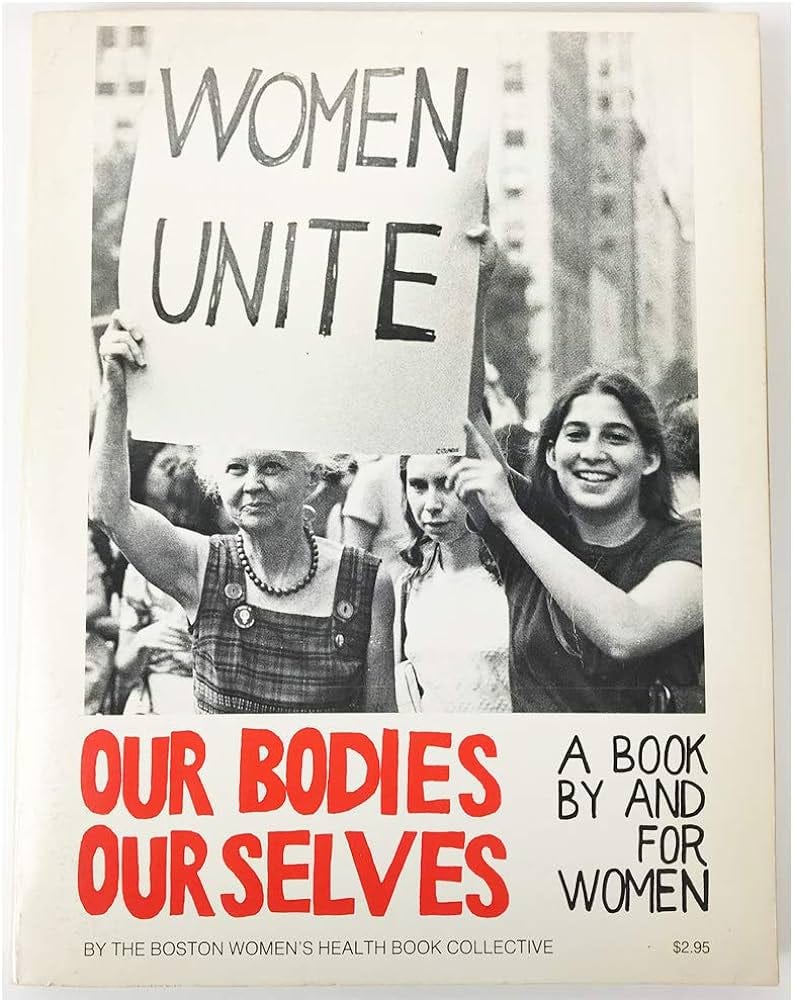

Yet the more I thought about it, the more intrigued I became. I wish I could say that I was solely motivated by the feminist movement that was swirling around me. Ms. Magazine had just published its first issue, with Wonder Woman on its cover, and Our Bodies, Ourselves was on every woman's nightstand. But though the feminist movement was certainly an influence, what excited me most the chance to explore a new way of autobiographical storytelling, using the medium of film rather than the pen, something I didn’t think had been done before. I knew that I wasn't interested in making the film Barbara suggested, but I did see the possibility of a film about the conflicts that would arise in my marriage, especially if l was going to continue my life as a working woman while being a new mother.

Joyce was able to raise funding from WNET in New York: “…they thought the concept novel enough to promise me $10,000, half up front, half upon delivery (no pun intended).” As she later recalled, “Now all I had left to do was produce the baby and find someone to do the filming for free. My hope was to break another barrier by collaborating with a female cinematographer, knowing full well that such a person might not exist; it was pretty much an all-male field. Luckily, Claudia Weill had recently graduated from Radcliffe College, had been using her boyfriend Eli Noyes's sync sound camera while making a few shorts with him, and was excited by the opportunity.”

The decision was made to start the film with the birth and then go from there:

“I entered my tenth month with no sign of a child coming. A week passed, then one more and then another with my doctor assuring me that everything was perfectly normal. Since I had a hard time sleeping—my belly was far too big to lie on—Tom kept me company watching reruns of the Sherlock Holmes Mystery Theater well past midnight. Claudia and I had kept in touch daily and, just our luck, she was out of town as I went into labor around 2AM. Tom managed to stay calm enough to hustle me to the hospital and reach a standby crew who showed up just in time to film our baby's overdue entrance into our world. In spite of the Lamaze breathing techniques, it hurt like hell and helped me to forget that a camera was pointing straight between my legs. It helped even more that Tom had been allowed into the delivery room—another barrier breaker —and stood by my side, squeezing my hand in encouragement. Then, two amazing things happened at once: the baby slid out and the pain stopped instantly. I faintly heard the doctor announce "It's a girl," with Tom's voice jubilantly adding, "It's Sarah Rose!" When the nurse placed baby girl Sarah Rose in my arms seconds later, I was almost afraid to touch her, she was so new.”

Claudia filmed Joyce attempting to cut film on a flatbed Steenbeck with Sarah on her lap and Joyce on set filming a documentary about a school, as well as many of the interpersonal parental negotiations between Joyce and Tom as they both attempted to find the time and space to do their work. Instead of filming consciousness-raising groups (such as the one captured by Lizzie Borden in her first film, the 1976 documentary Regrouping), Chopra turned her camera towards her mother’s friends:

The scene that turned out to exceed all my expectations and may be the best part of the film was my mother’s monthly luncheon with the retired and still feisty Brooklyn teachers she worked with at PS 253 in Brighton Beach. It’s certainly the most delightful. After the women had greeted each other, traded the latest photos of their grandkids and gossiped, I asked if I might pose a single question: "Did you ever feel conflicted about working and raising a family?” It was as though I had set off a bomb underneath their seats. Their answers came out in a rush. As hard as it is to believe now, it seems that in all the years they had eaten lunch together in the teacher’s lunchroom, the women had never talked about it. Claudia and I knew, even as we were filming, that we were witnessing their consciousness "rising." All ten of them kept talking excitedly, well after we had turned off the camera, interrupting each other with their own stories. "If I stay home, I'm bored, and that's not good for him. If I go to work, I come home tired, and that's not good for him either. Whatever we do is wrong." "If you found out you were pregnant, you had to leave at once!"

The half-hour-long film premiered on PBS in 1973 and was the first live birth ever seen on television. Finding distribution beyond PBS proved difficult; as Chopra recalled later, “There were a number of companies that marketed films to public libraries and colleges but not one of them thought there was a large enough audience for documentaries about women’s experiences to be profitable.” Other female directors were being confronted with the same frustrations with mainstream distribution channels and decided to take the issue into their own hands. In 1971, feminist filmmakers Julia Reichert, Liane Brandon, Amalie Rothschild, and Jim Klein founded New Day Films as a film distribution cooperative, primarily serving the non-theatrical market (colleges and universities, libraries, high schools, and community groups). According to Brandon and Reichert, “The whole idea of distribution was to help the women's movement grow. Films could do that; they could get the ideas out. We could watch the women's movement spread across the country just by who was ordering our films. First it was Cambridge and Berkeley, and then the first showing in the deep South.” Weill and Chopra joined the cooperative, where “jobs were split up, including the compiling of mailing lists, but it was up to each member to design, print and mail their own advertising brochures, for which we were lucky enough to get blurbs from Gloria Steinem and Shirley MacLaine.” Joyce at 34 went on to be a distribution success, with copies sent for viewings across the nation; for Chopra, “Each 16mm print that I put in a film can and hand-carried to the post office felt like a small victory.”

Joyce at 34 also went on to receive the American Film Festival Blue Ribbon award. Overall, the reviews were largely appreciative. The New York Times critic wrote, "This is not a feminist film, though clearly aware of feminist positions, but is a film about people of three generations and many loyalties and ambitions, and many ways of accommodating to life as a complex and viable continuum—and that insight is perhaps as close to ecstatic perception as the documentary film can get." In the July/August 1974 issue of Film Comment, it was described as “one of the most honestly open and least patronizing film portraits I’ve encountered. The family of Joyce and the early scene of her giving birth appear so free of rhetoric and attitudinizing that one has the illusion of watching such people and such an event for the first time on a screen; which is to say that Joyce at 34 is the nicest fantasy I’ve seen in quite a while.” Gloria Steinem called it, “One of the rare documentaries that is neither propaganda nor put-down; a film that loves both the people it portrays and the truth.”

Not everyone was so kind; as Chopra later recalled, she was “excoriated by Ruby Rich, the Marxist film critic for the Village Voice, for being privileged and not at all representative of most women.” This was a complaint I found repeated in feminist journal articles from the 1980s. In her essay “Theories and Strategies of Feminist Documentary,” E. Ann Kaplan wrote in 1982, “In Joyce at 34, all mention of class and of economic relations is suppressed, so that we are never allowed to focus on the privileged situation that Joyce enjoys with her freelancing husband (he can be home much of the time) nor the support of her comfortably middle-class parents. The cinematic strategies here work to suture over conflicts and contradictions as in a Hollywood film… And as representation, Joyce does not in herself threaten accepted norms, while her unusually handsome husband adds a gloss to Joyce’s environment which, in any case, fits the bourgeois model of commercial representations. The structure of Joyce at 34, thus, perpetuates the bourgeois illusions of the possibility of the individual to effect change and of the individual’s transcendence of the symbolic and other social institutions in which he/she lives.”

Everything about Joyce at 34 is autobiographical. Chopra wasn’t concerned with telling a more universal female story or even situating her own female story within a larger discourse about society—she was attempting to tell her story at a time when it was wholly uncommon for a woman’s story to be told in such a way. It’s that of a woman trying to balance an uncertain career—one marked not just by the uncertainty of freelancing, but also by the uncertainty of being a woman in a field where her work is constantly devalued due to her sex—while also coming to terms with her style of motherhood as a bohemian creative in opposition to the more bourgeois values of her parents. Her experiences speak to new mothers’ experiences today—those written about in Instagram captions, Substack newsletters, and confessional memoirs. By filming herself giving birth and talking honestly about the identity crisis of motherhood, Joyce Chopra was a “crucial forebear of generations of first-person filmmakers” (in the words of Richard Brody at The New Yorker) and helped lay the path for those confessionals and conversations. The value in watching Joyce at 34 comes from seeing how little has changed; women today might be more comfortable talking about their fears around motherhood and loss of identity, but restrictive societal structures around childbirth and motherhood and womanhood remain.

While Chopra was later to direct the acclaimed feature film Smooth Talk in 1985 (based on a short story by Joyce Carol Oates and with a screenplay adapted by Chopra’s husband, Tom Cole), every step of her directing career was repeatedly thwarted by males in positions of power. Her memoir, Lady Director: Adventures in Hollywood, Television and Beyond, details the many doors closed and projects taken from her, beginning in the early 1960s (when she was told by film companies to apply as a secretary) and continuing until today. The documentaries she’s made about women’s issues—whether autobiographical or on specific institutions or programs—are her continual attempt to center a female voice and a female narrative.

Joyce at 34 is available to watch in its entirety on Vimeo:

Thank you for this! I will definitely watch this!

Saw “Smooth Talk” last year (?) on Criterion, from a female view, a scary film.