Janice Wainwright 1940-2023

In Memory of a Designer of Dreams

As Janice Wainwright was among the group of London-based designers that have long been my absolute favourites—Ossie Clark, Thea Porter, Bill Gibb, Zandra Rhodes, Jean Muir—for well over a decade I made many attempts to connect with her for an interview. Over the years I tried any route I could think of to get in touch with her, and just this spring I reached out to her former stepdaughter who provided a few possible leads. Unfortunately, a month later, I received a message from her former stepdaughter stating that Janice had passed away at age 82. Her death warranted just short bios in some British newspapers—nothing up to the level of her work and the success she had. Below is a longer exploration of her career and designs, a small step towards rectifying the lack of information on her on the internet.

From a coal mining family, Wainwright was born in the small village of Doe Lea, Derbyshire. Both of her parents had dropped out of school at fourteen, before later finding security in Ministry of Defence civil service jobs. Raised in council houses in Wimbledon, south-west London, when Wainwright was twelve, the headmistress of her school offered her free Saturday morning art and design lessons; “From that moment on, I looked at fashion as an escape from reality.” Channeling all her energy towards fashion, at 15 she attended Wimbledon School of Art, then Kingston School of Art, before finally winning a spot at 20 on the fashion course at the Royal College of Art, under the visionary professor Janey Ironside (who I’ll return to in a future newsletter.) There Janice met Ossie, Zandra, and Marion Foale, and was taught that “fashion should be more than a transient look transmitted through images: clothes could be physical pleasures, and should serve their wearer’s identity, not subsume it.” While at school she began designing part-time for the mass-market manufacturer Simon Massey, who was seeking to create affordable versions of hip boutique clothes.

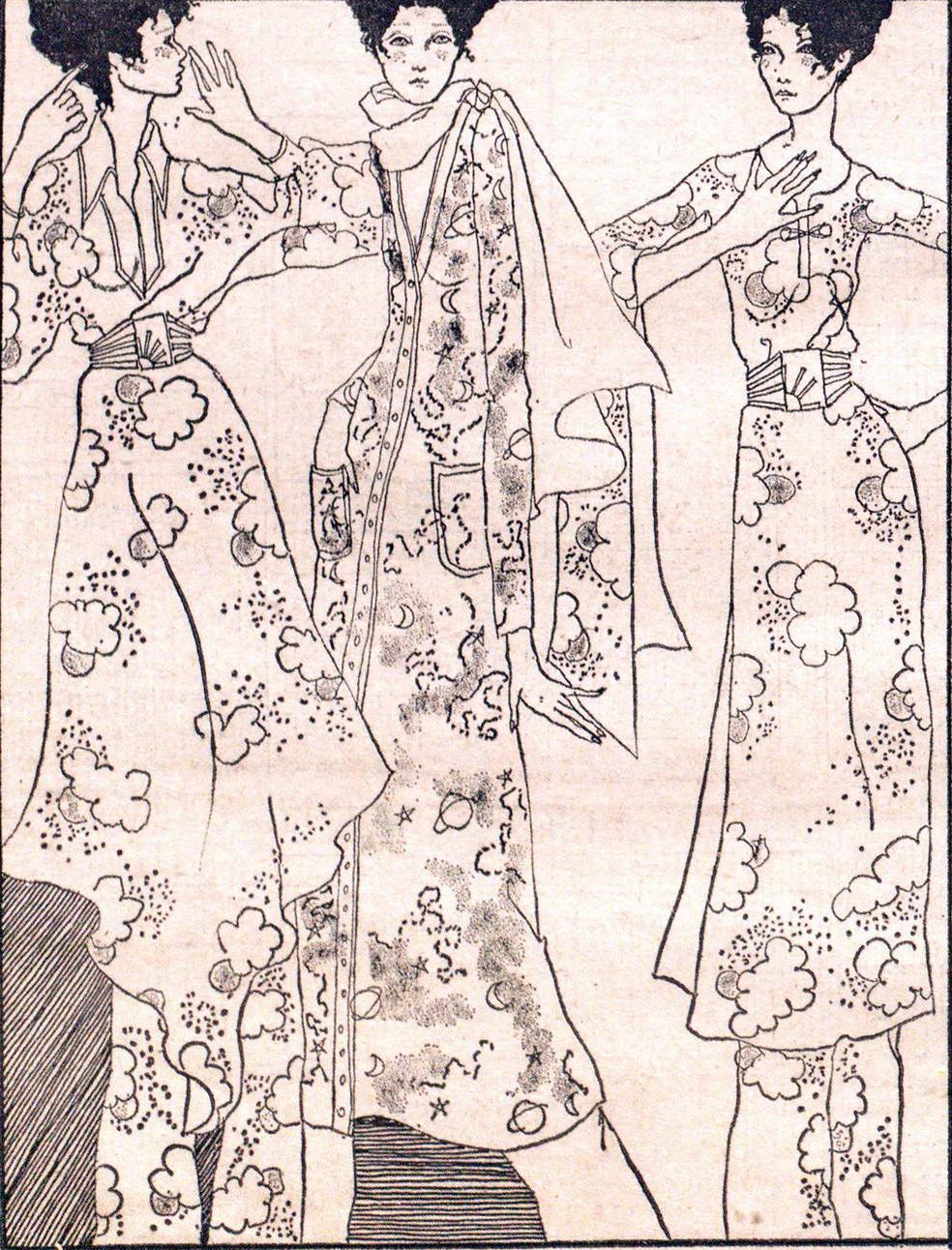

Soon after she graduated in 1965, Simon Massey gave her own “designed by” label. When profiling Swinging London fashion in 1966, Women’s Wear Daily wrote: “Simon Massey has the prettiest collection of all. We think designer Janice Wainwright has done an excellent job of designing a collection with a unified look… a look of elegance with a youthful beat.” From the start, Wainwright leaned heavily on revival styles. She was credited in the press as being the first designer to bring back 1930s-style slipper satin, and she was among the earliest to inflect her designs with 20s, 30s, and Victorian silhouettes and motifs. For her, it was “not really nostalgia. I’m not looking back. I can’t be because I obviously don’t remember the originals.” Drawing from the same inspiration as Barbara Hulanicki’s Biba, in 1967 Wainwright blew up intricate Art Nouveau patterns and paisleys onto high-necked, puff-sleeved mini-dresses that had the press calling her, “the most talented youngster in Britain.”

“I think things should be absolutely simple and beautifully decorated.” – Janice Wainwright, Women’s Wear Daily, 1969

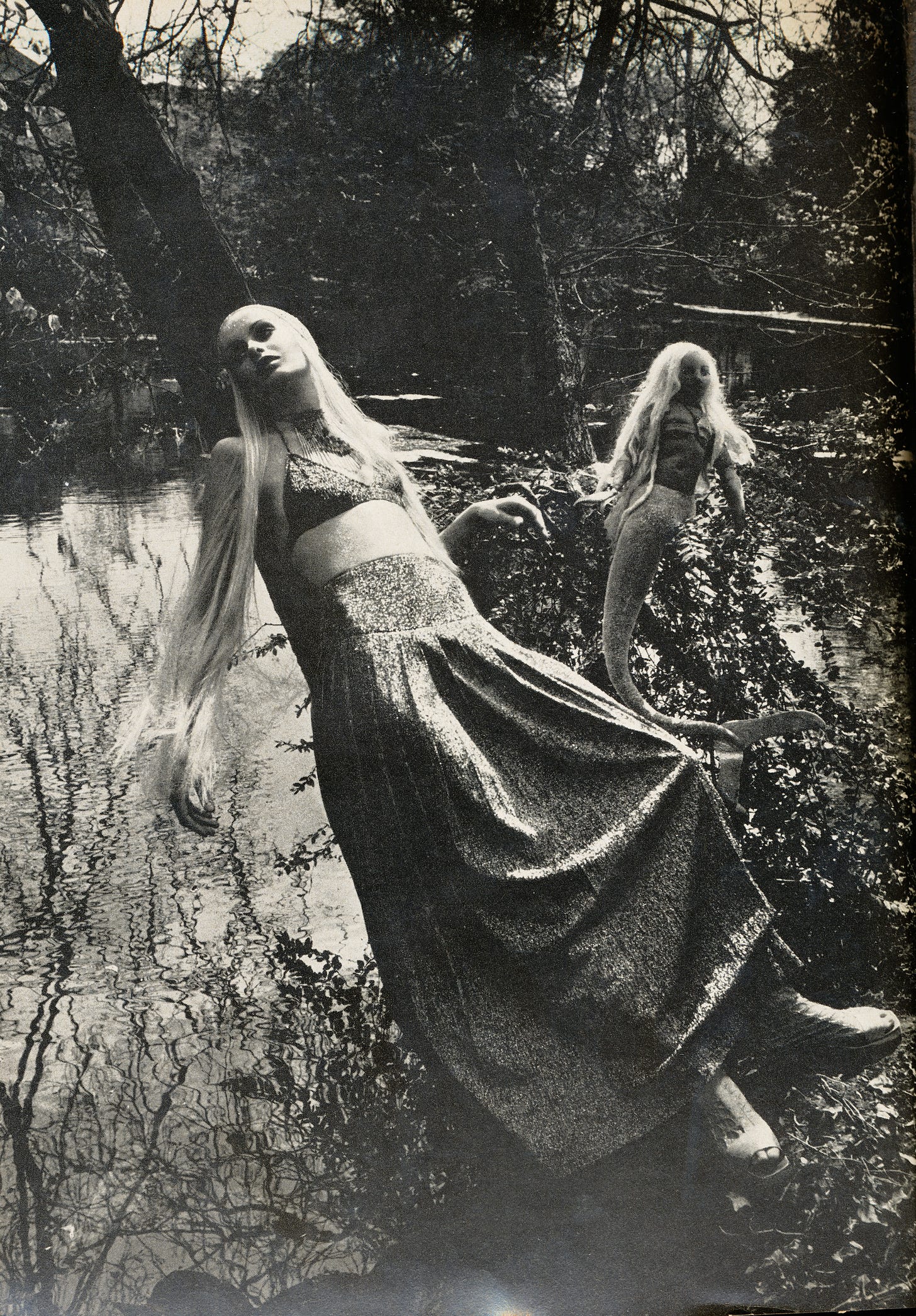

Janice—with her pale skin, arched eyebrows, and long centre-parted dirty blond hair—designed clothes for young women like herself: hip young women who were romantic and dreamy, totally of the moment yet also engaged with history and mysticism. Her spring 1970 collection featured “lots of shimmering pale jerseys for day—tapestries patterned one over another in medieval splendor; glittering sheer, nearly transparent jerseys patterned with waving grass and trees—and her newest jerseys, printed with the ‘elements’”—of which she told WWD, “I wanted to do something very magical and mysterious, but very sophisticated, but done in the simplest terms.” Not all of her designs were historically inspired; one successful collection in 1967 featured simple sheaths and separates made from East African khanga clothes (seen in the video below), tying in with the hippie interest in “ethnic” clothing.

In the late 1960s, Wainwright married the photographer David Cripps—then a fashion photographer, though he later would become known for his photos of objects and crafts—and they moved to a restored Georgian house in Islington, “the area (with Notting Hill Gate) London’s creative young are steadily moving to.” A passionate antique collector, the couple spent their spare hours puttering around junk shops—soon their home was filled with Persian carpets, Victorian bamboo furniture, and “the Twenties’ things Janice loves best of all.” While on a trip to the United States, Janice discovered a trunk at a junk shop outside New Haven stuffed with “over 150 old Twenties’ and Thirties’ samples, all crepe de chine… they were more beautiful than any prints I’d seen done in the last 30 years.” After recoloring them, they became the basis of her spring 1969 collection. Janice and David had a son in 1970 and divorced in 1973.

“When evening falls, a fantasy descends on the world. It’s as if the harshness and rush of the day is set aside and a woman can transform herself into a fictional character.” – Janice Wainwright, Boston Globe, 1975

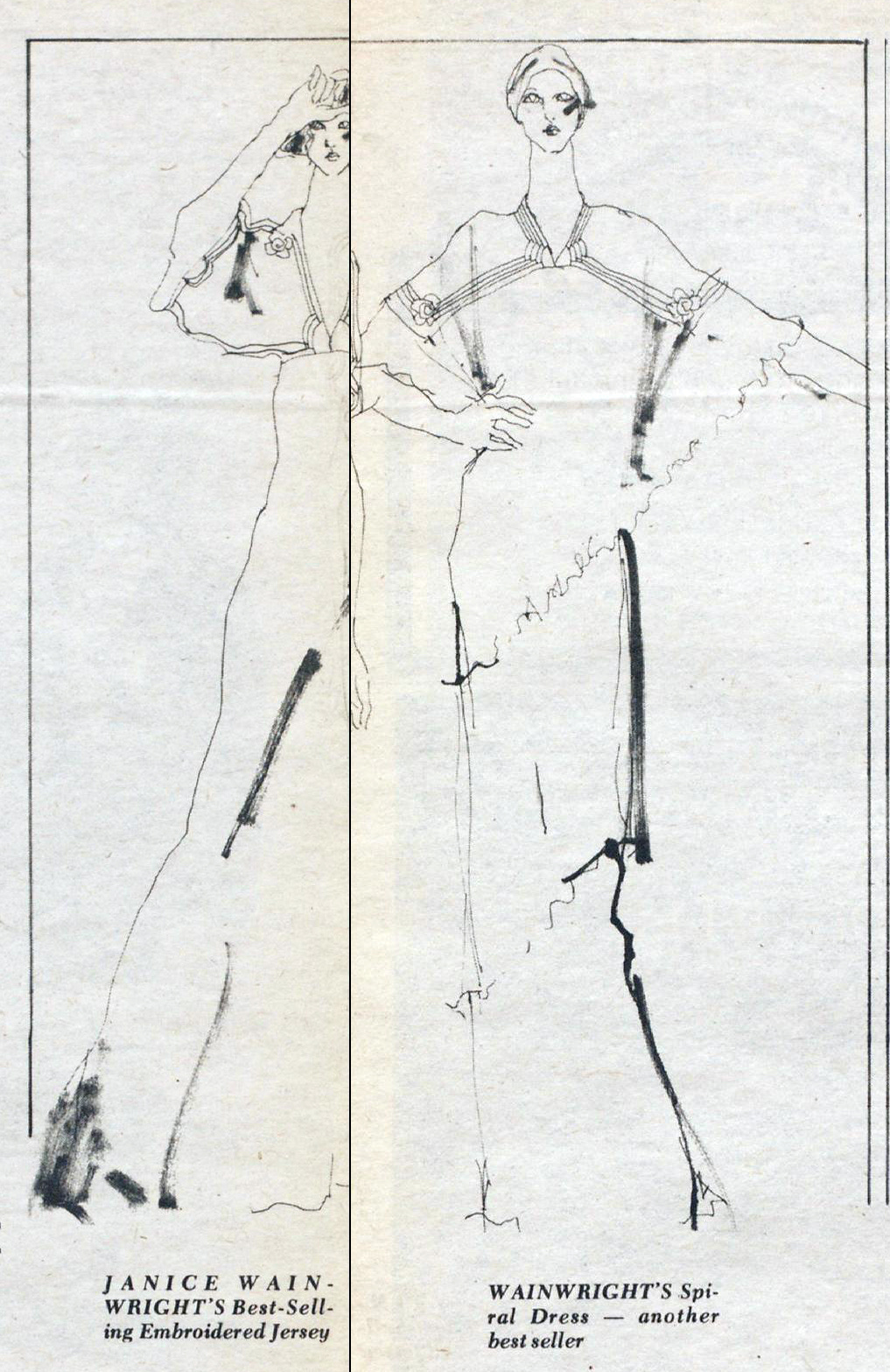

Though Simon Massey gave Wainwright quite a bit of control and freedom, the needs of the mass market were inherently limiting. Though she could design her own fabrics or hire textile designers she admired (Janice was the only designer in the 1960s, other than Ossie Clark, to be allowed to use Celia Birtwell’s prints), to make the printing financially feasible it had to be done on unsuitable cheap fabric. With private financial banking, she established her own company in 1972—named 47 Poland Street after the new address. Now able to set her own prices, she began to use much higher-end textiles. “I decided it would be fun to go out on my own,” she told WWD in early 1973. “I’m much more free to do my kind of work. I’m doing designer clothes and I’m very aware of line and cut.” Whereas Janice Wainwright for Simon Massey had been picked up by American department stores for youth departments and “Swinging London” promotions, with 47 Poland Street Janice now found her designs in the designer rooms of the nicest specialty stores and department stores, nationwide. With her own collection, Wainwright began to play with the embroidery and appliqué that were to become her signature. In around 1974, the label was changed to simply say “Janice Wainwright.”

By 1975, when she showed her collection as part of an exhibition of British fashion at the Inn on the Park Hotel, Janice Wainwright was ringing more than half a million dollars in orders in three days. She was widely considered one of the hottest houses in London—her designs more fanciful than Jean Muir yet more wearable than Zandra Rhodes. “I became known for my embroideries rather than the fabric I put them,” she admitted in 1976. “But I also develop all of the fabrics.” Those exclusive fabrics—cottons, rich matte jerseys—contributed to the high price of her garments, though the embroidery was the main cost amplifier. According to her business partner Geoffrey Caine, each embroidered panel on a tunic top contained “over 35,000 stitches. We have machines working 18-hour days, six days a week.” The embroidery was done in Austria and Switzerland. Her evening wear retailed from $350 to $490, roughly $1,880 to $2,632 today. By the age of 38, her company’s annual turnover was £1 million.

“I think I make clothes for thinking people who are aware of design and prefer to live their lives surrounded by good design rather than bad. They are people who like to look splendid from every angle…” – Janice Wainwright, The Guardian, 1981

Flowing matte jersey—often cut lean like the 1930s—was a regular staple in her collections though, as the decade went on, Wainwright began to incorporate many other textures, details, and silhouettes. Her fall 1979 collection was particularly admired—described as a “show that was professional, well-edited, beautifully accessorized and had a taste level that was missing in most of the collections presented…,” it included black tailored suits with metallic trim and “a knockout group of iridescent mushroom-pleated long dresses with an asymmetric hip detail.” In 1980, she became known as a proponent of dropped waist and waistless dresses—at times flapper style, in other collections more columnar—in luxurious fabrics.

Each collection built off the last in what she called “handwriting progression”—maybe taking fabrics or colours or silhouettes forward, while subtly adapting them. The effect was timeless, achieved because “each collection is a development of what has gone before. If a designer has a coherent concept of a way women want to dress, there is no room for sudden changes of direction. That is like confessing you’re confused, adrift, lacking in confidence—and if the designer lacks confidence, pity the poor customer.” Thirties lines mostly gave way to revivalist touches, in keeping with the New Romantic movement and the return to romance embodied in the young Lady Diana Spencer. Wainwright’s collections soon were composed of velvet knickers and ruffle-trimmed silk blouses, peplum jackets, and leg-o-mutton sleeves.

“To make money making beautiful things is tough going and pretty rare, but if you can stay ahead and in control, it’s a lovely, wonderful game.” – Janice Wainwright, The Guardian, 1981

In 1989, Janice Wainwright declared bankruptcy; it is unclear what caused the downturn in her business, but many of her contemporaries’ businesses suffered during that period. At that time, she decided to mainly retire, solely designing a smaller collection of plus-size clothes for the next few years. In the early 1990s, Janice moved to Sydney, Australia. There she reencountered the artist and architect Rollin Schlicht, who had studied at Kingston School of Art in the late 1950s (around the same time as Janice) and been part of bohemian London until around 1966. They married and were together until he died in 2011, after which she returned to England in 2017. Janice passed away on June 3rd, though her death was not announced until later that month.

I believe that this is the home and studio Rollin built for them in Mount Kuring-gai, a suburb of Sydney, in the late 1990s.

No matter if her designs were redolent of medieval minstrels or an early Chanel, Wainwright always made them her own; highlighting “the line of the collection with subtle detailing, tracing the edge of a collar or the curve of a seam with contrast piping, or echoing the print of a fabric with a bolder, contrasting applique.” You can always tell a Janice Wainwright garment: Wool suits with appliqué and embroidered trim… Bias cut dresses embroidered with Art Deco or celestial motifs… Cocoon coats in devoré velvets… Matte jerseys and chiffons… Sparkles… A mostly black palette livened up with plums, ochres and other off-colours… Though her designs echoed larger trends, she always used them within her own signature.

“Really good design is like a chameleon, it changes to suit the individual.” – Janice Wainwright, The Observer, 1983

And yes, that is Rollin's property at Mt Kuringai - I visited and even stayed there. An amazing spot.

Hi there, Janice was a friend of mine, so I can correct some of your information. Firstly, Janice moved from London to Sydney to marry and live with Rollin, with whom she'd been involved on and off for decades, she didn't move to Sydney and then rediscover Rollin. Secondly, Rollin had already owned the place at Mt Kuringai where Janice lived with him. Thirdly, that is indeed Rollin in the centre of the above picture, but that isn't Janice!