Bringing Splendor Back to the Ballet

Harkness House

As she was described in the first line of her Los Angeles Times obituary, Rebekah West Harkness was a “modern-day Catherine de Medici, who gave millions to support ballet and medical research.” A truly fascinating character, Rebekah was the recipient of some attention a few years ago as Taylor Swift wrote a song about her and owns Harkness’ Watch Hill estate; you can read more about their connection here. Today I’d like to talk about Harkness House, the mansion she created for her ballet company and school, but first a little background.

West grew up in wealth and privilege in St. Louis and later came into great fortune with her second marriage, to Standard Oil heir, William Hale Harkness. When he passed following a string of heart attacks in 1954, she inherited many millions—though often recorded in the media as being as high as $450 million. her biographer Craig Unger states it was $27 million ($304,500,000 today, adjusting for inflation).

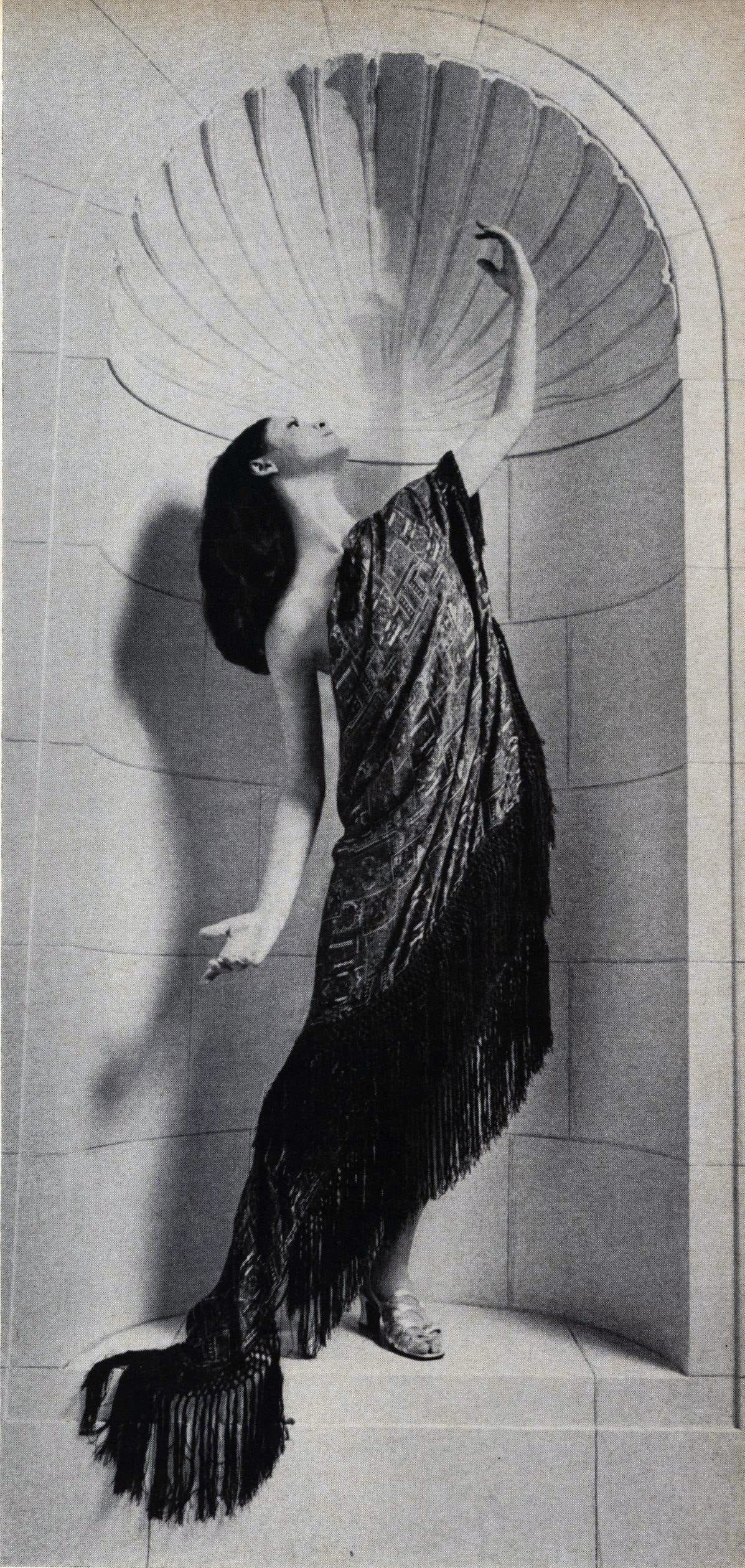

Considering herself a dancer, sculptor, and composer, Rebekah swiftly set to becoming a patron of the arts. Primarily supporting dance, she sponsored Jerome Robbins’ “Ballet: USA,” Pearl Primus, Marquis de Cuevas, José Greco, and others. Her support of Robert Joffrey was vital in the establishment of the Robert Joffrey Theatre Ballet (later renamed the Joffrey Ballet); as his benefactor, she invited him and the entire dance company to spend the summer of 1962 at her Watch Hill estate, Holiday House, preparing for an international tour that fall. The tour and the ballets she commissioned (from the likes of Alvin Ailey) were a major success, establishing her as one of the great patronesses of dance. There were copious disagreements behind the scenes, mainly revolving around Joffrey being unwilling to use Harkness’ compositions for ballets. In early 1964 Harkness grew tired of pouring millions into a company that wouldn’t use her music and she decided to set up her own ballet company, stealing most of Joffrey’s dancers from him. She offered him the role of artistic director but wouldn’t guarantee him final say on the artistic direction. All the costumes, sets, musical scores, and entire repertory belonged to the Rebekah Harkness Foundation. Joffrey was left with nothing, while Rebekah now had her very own Harkness Ballet.

One of her first orders of business was finding a home for her new company. That June she purchased a 25-room mansion at 4 East 75th Street on the Upper East Side of Manhattan for $625,000 ($6 million today). Designed by Trowbridge, Livingston and Colt, the mansion was built in 1896 for stockbroker Nathaniel L’Hommediue McCready Jr. It was then owned by V. Everit Macy (another Standard Oil heir) and his wife, who turned it into a rest home for American soldiers in WWI. After the war, it passed to Stanley Mortimer (another stockbroker) and Elizabeth Livingston Hall. The founder of IBM, Thomas J. Watson, purchased the mansion in 1940. Following his death in 1956, it was owned by the widow of Hollywood producer William Fox (the Fox of 20th Century Fox), Eva Fox.

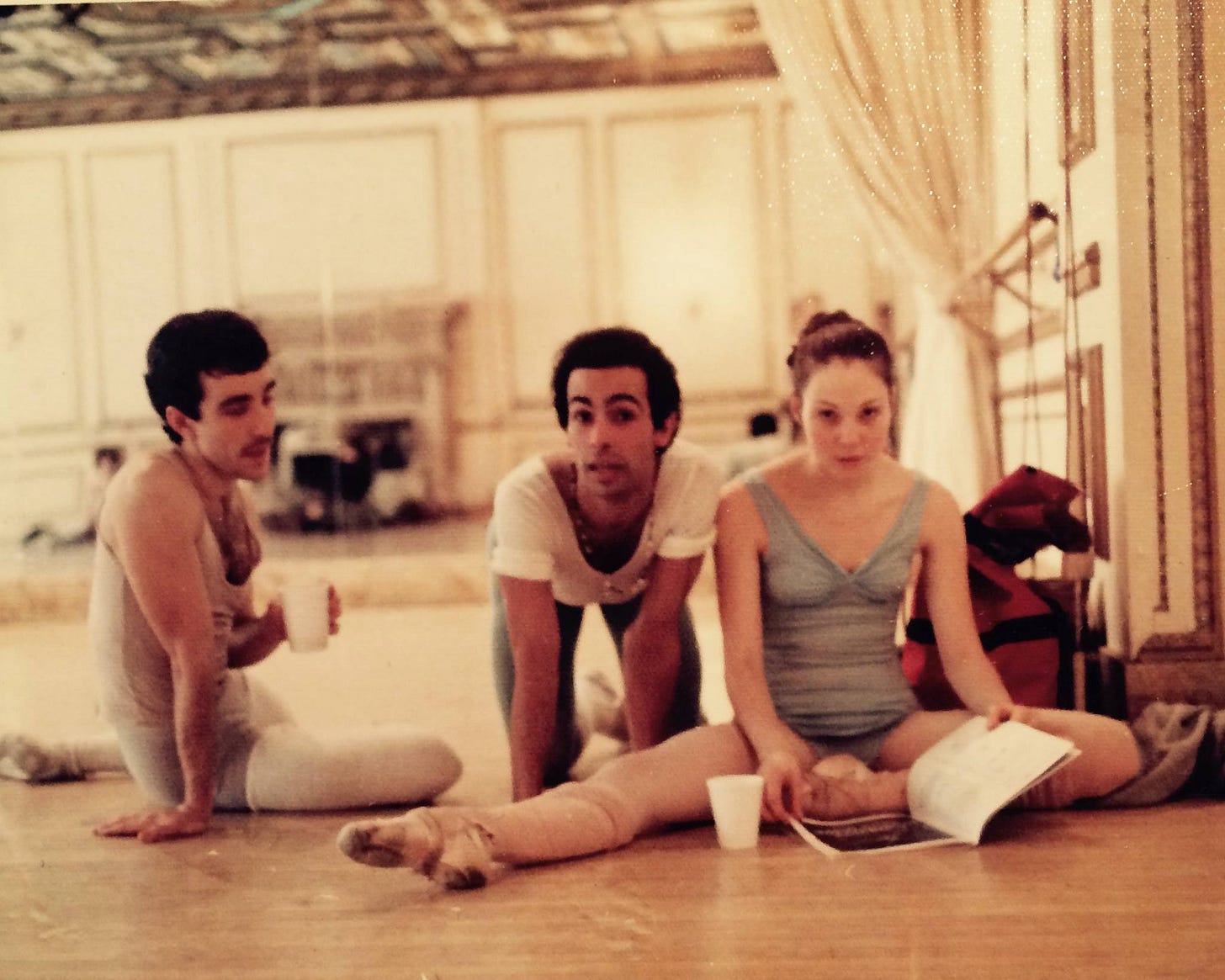

Rebekah set to work on a massive restoration, renovation, and redecoration of the 20,000-square-foot space that took around 16 months. As Unger states, “It was not just an office, school, and dance studio; it was a home for Rebekah’s extended family of thirty-five dancers, fifty trainees, and ten staff members, in the tradition of the Imperial Ballet School in nineteenth-century St. Petersburg.” Robert Bradbury of Rogers, Butler & Burgun was hired to redesign the space, while society decorator Michael Greer was brought in for the interiors. Remaining from McCready’s time were hand-carved walnut paneling and ornamental ceilings, and massive marble mantels; during his time there, Watson changed the original central staircase into an elegant sweeping curve.

“I want to give splendor back to ballet. I think today our artists deserve such elegance, for they are our true aristocrats.” - Rebekah Harkness

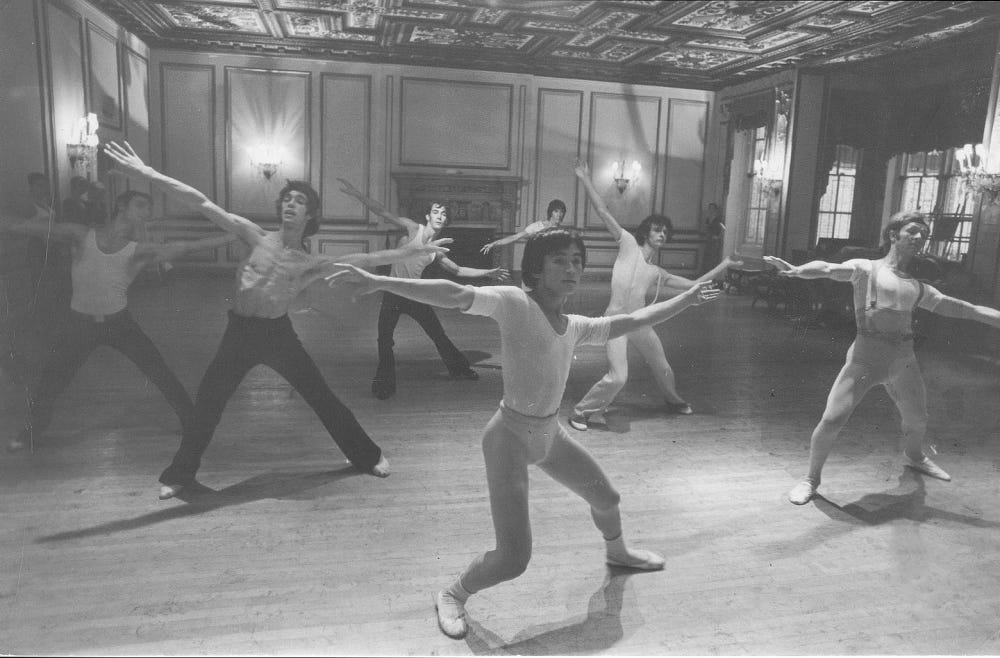

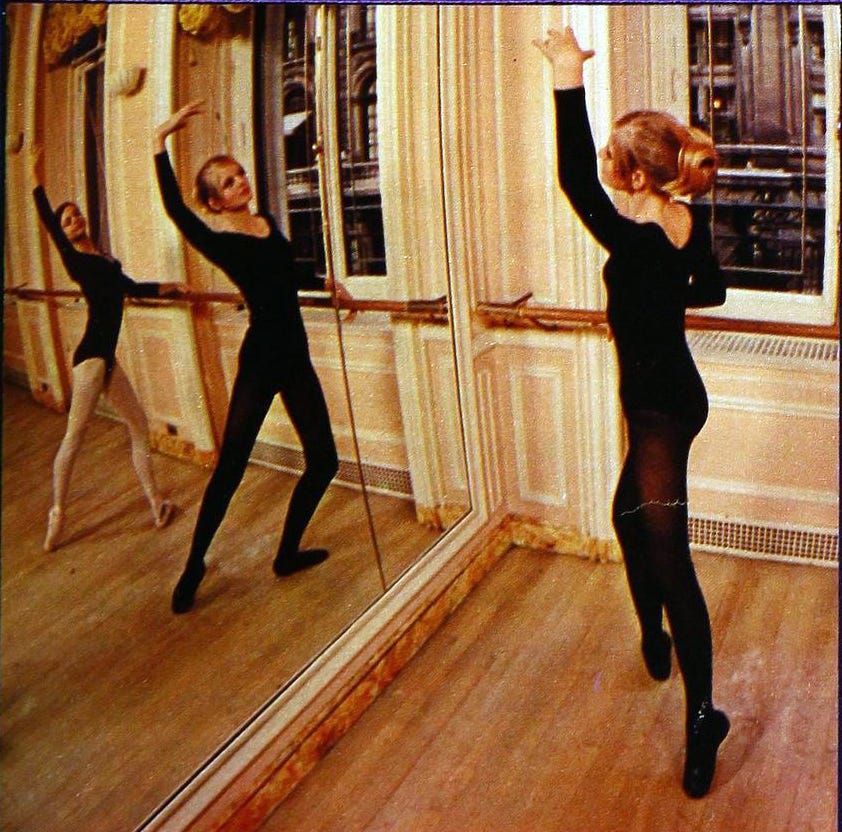

As Harkness explained after the opening, “Really what this place does is save energy. Everything that’s needed for the dancer’s day is here—rehearsal rooms, fitting rooms, a cafeteria, a place to read or listen to music.” The five floors soon contained four dance studios, a music classroom, a costume room, locker rooms, masseur’s room, bathing facilities, a laundry, record-listening rooms, a canteen, administrative offices, Rebekah’s private office-apartment, amongst other formal areas. Bradbury even transformed a covered driveway into an art gallery, with skylights flooding the long narrow space and black-and-white marble covering the floor.

A classicist with an eye for color, Greer was the ideal choice of decorator. He added French crystal chandeliers and sconces throughout and had the Italianate ceiling of the main ballet studio repainted in blue and white, the ballet company’s colors. That color scheme was used across the house, with emphatic touches of ruby red brocade and velvet. Each of the four dance studios was fitted with special springy floors, hung with eight-foot mirrors and barres, and given its own color—peach, red, gray, and blue—which was either used for the walls (such as red fabric) or for window coverings (shirred blinds and curtains).

Following Rebekah’s advice, electric blue velvet was used for the 30-foot-long curtains in the hall. A room with a “magnificent beamed ceiling became the library, decorated with thick red rugs, velvet wall coverings, an elegant chandelier, leather furniture, a portrait of William Hale Harness, and sculptures Rebekah herself had done.” The cantina’s ceiling and walls were painted to call to mind the Italian countryside as seen from a stone loggia.

While Thomas Watson had liked the elevator to be “pure and glistening white,” Harkness had a more elaborate idea in mind. It appears that the whole elevator cage was covered in heavily beaded and sequinned panels, while the inside of the elevator was painted with scenes from famous ballets: “Swan Lake,” “Daphne and Chloe,” and “The Firebird.” Lee Pilcher and his assistant worked round the clock up until the opening night party on November 18th, 1965, hurriedly working to create a dazzling jewel box of a space.

“Up at Harkness House, the tiny jeweled elevator shoots up its floral shaft to the third floor. Then, it’s up a short flight of stairs to a white door guarded by a pair of Portuguese Santos and a brace of framed White House Christmas cards.” Behind that door was Rebekah’s private apartment, which stretched across the top floor. There were two grand pianos, and her living room had rose-velvet walls and rose-colored Austrian curtains.

A floor of black and white marble offset the white walls of the reception hall, with Watson’s elegant staircase curving up to a magnificent Louis XVI crystal chandelier. At the end of the reception hall in a glass-enclosed niche was the pièce de resistance—Salvador Dalí’s Chalice of Life. A personal friend and patron of Dalí, Harkness purchased the chalice directly from him that year at the time of its completion. “Out of a base of gold and malachite grows a tree in sculptured relief that winds around a seventeen-inch-high golden urn. Some of the leaves give the appearance of being half devoured by caterpillars. Others open mechanically into jeweled butterflied studded with diamonds, emeralds, sapphires, and rubies.” A Swiss watchmaker created the internal mechanism that allowed the butterflies to flutter their wings. The sparkling urn slowly revolved, dazzling all who entered.

“I may have overdone it, but it really doesn’t cost that much more to make things beautiful. I’m very sensitive to my surroundings and I think most people are.” - Rebekah Harkness

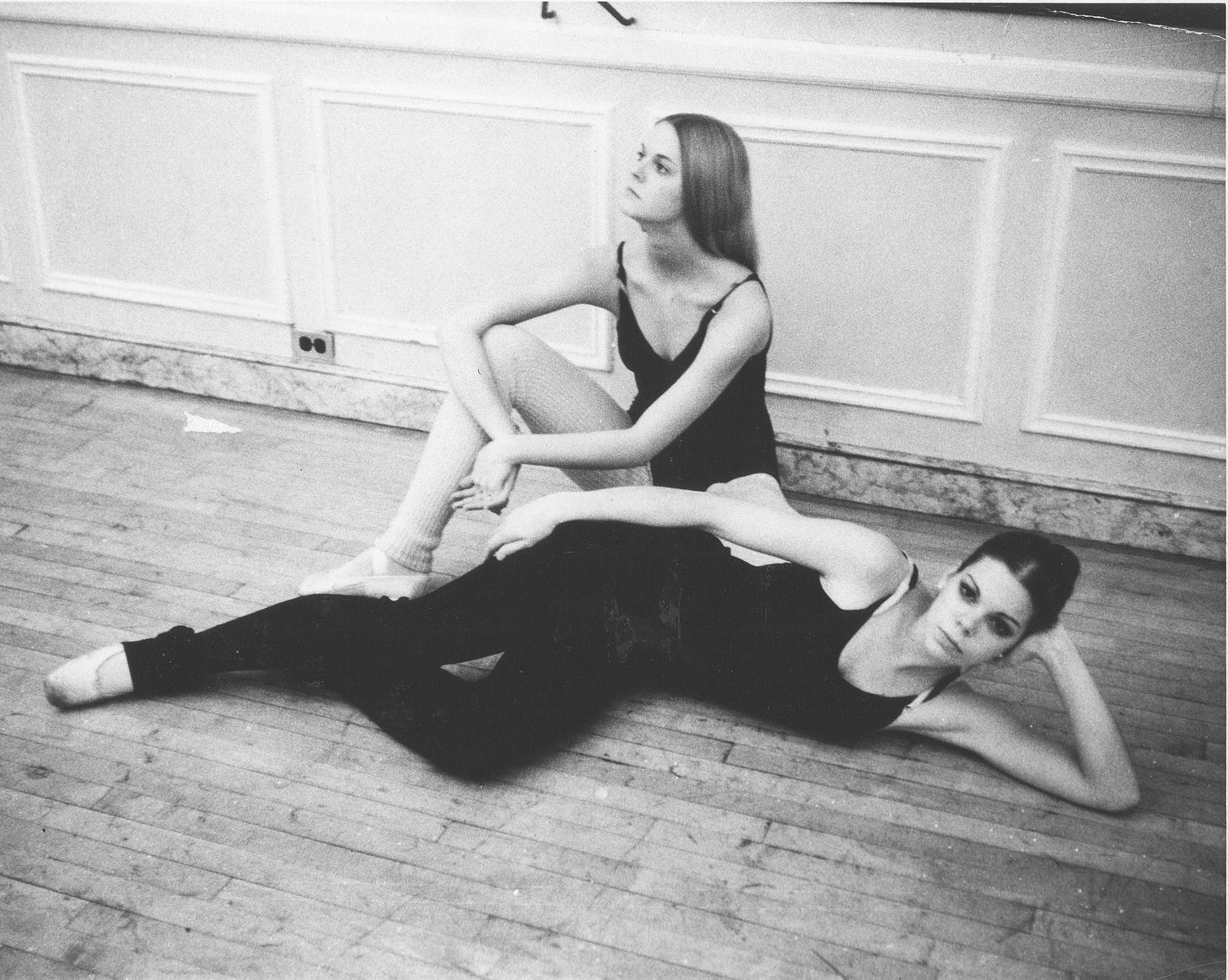

While dancers began practicing there on November 1st, the gala opening took place two weeks later on the 18th. Guests made their way up the elevator or stairs to an assigned rehearsal room, where they watched ballet dancers practicing at the barre and drank cocktails. Descending, they made their way to the “Gallery of Dance” on the ground floor to take in an exhibition of ballet designs from Serge Lifar’s collection, all created for Diaghilev and lent by the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford. Around 10 pm, select guests crowded into a downstairs room for the official opening—Mayor Wagner presented Rebekah Harkness with the city’s bronze medallion of honor. Everyone headed back upstairs to dine on lobster and steak in the rehearsal rooms while dancers pirouetted in between the tables. For the evening Sybil Williams (recently divorced from Richard Burton) and her new husband Jordan Christopher decorated the first-floor rehearsal room after their discotheque Arthur. Mondrian-type panels were applied to the walls, complemented by powder blue tablecloths and fat red candles—WWD decried it as a “half-hearted Mondrian effect of red/blue/yellow cellophane blocks.” The blue and gold ceiling of the second-floor rehearsal room was paired with yellow tablecloths, while the red-walled “Spanish Room” on the third floor had pink tablecloths, hot pink centerpieces, and pink votive candles. Dalí appeared early, Marisol stayed the whole night, and the president’s daughter Lynda Byrd Johnson came by late with a Secret Service detail. The night was a success with Rebekah Harkness seemingly enshrined as a major player in the dance world.

While the Harkness House for Ballet Arts was almost immediately respected as a top-quality school turning out highly skilled dancers, the Harkness Ballet continued to have a more difficult time establishing itself with frequent changes of artistic directors (caused by Harkness’ ego, desire for fame and easily swayed opinions) leading to instability and unrest. At one point in 1970, all the dancers in the main company were dismissed and replaced with the trainee dancers of the Harkness Youth Dancers. The details and drama are far too complex to get into here, but the Harkness Ballet was beset with problems—finally closing in 1974 after a decade of losing money.

The school continued—bolstered by the highly respected dance teacher David Howard, who was its director. After he quit in 1977, the school limped on—by that time Rebekah had lost interest, the school just a symbol of her dashed hopes. In an effort to make some money, her administrators often rented out the building for private parties, but there were often no staff left to clean up afterward. One dance teacher later recalled, “The contrast was unbelievable. It had been a spotless, elegant townhouse, very open sexually, with gorgeous men and women hanging around in tights and leotards, the finest dancers, doormen, great paintings on the wall. Now there were no standards. The worst bunch of untalented people. Magnificent pianos left untuned. The lights were literally dimmed—the used twenty-five-watt bulbs.” Hence the new nickname, Darkness House.

In 1979, American former ballet dancer Nikita Talin took over as director of the school with the assistance of his friend (and Rebekah’s longtime lover) Bobby Scevers. When later asked about the disintegration of Harkness House, Bobby replied, “There was just nothing left of the school. The draperies were ruined. The building smelled to high heaven. It looked like some horror movie place fallen apart.” Though they proclaimed that they wanted to return it to its glory days, its descent continued: dancers complained of slippery floors following private events, bathtubs were filled with cigarette butts and dirty linens.

At the time of Rebekah’s death in 1982 from stomach cancer, Harkness House was seemingly beyond repair. Unger writes, “In its current state of decay, it was an ironic reflection of Rebekah’s shattered dreams. It reeked of overripe opulence. Its marble floors smelled from spilled hors d’oeuvres left to spoil. One visitor likened it to an aging, once beautiful woman whose wrinkles were painted over with too much makeup.” The Harkness House for Ballet Arts closed in 1985.

Harkness House was sold in 1987 for $7 million to TV and film producer Jean Doumanian, with all proceeds going to Rebekah’s foundation. Doumanian lived there until 2006 when it was sold for $53 million to private equity broker J. Christopher Flowers. He apparently gutted it, then lost many millions in the financial crisis of 2008 and was unable to complete the renovation. Following the housing market crash, Flowers sold the mansion to Larry Gagosian for $36 million in 2011. Gagosian and his architect Anabelle Selldorf completely rebuilt the inside—the limestone façade is all that remains of Harkness House today.

More on Rebekah Harkness this weekend, looking at another interior renovation-cum-money pit.

Thoroughly engrossing! Thank you.