Madame Halicka

An Overview

This newsletter was supposed to be sent out early this morning but a bug prevented that—while I believe none were delivered if you are getting this for a second time, I apologize!

Several months ago I came across the below collage in the January 1938 issue of Vogue. The caption states: “A new wide-woven wool for spring and summer, crisp, cool, and uncrushable, is Forstmann’s ‘Porosa,’ used for the model. Madame Halicka, who employs fabrics instead of paint as a medium, made this picture.” The carefully shaped fabric sleeves and skirt, the tiny knotted belt, the small artificial flowers set on embroidery floss hair—enamored by the whimsical sensibility of this piece, I wanted to find out everything about this “Madame Halicka.” In this newsletter is a biography of her and her work, focusing on painting and the complexities of her life as a female artist; Friday will be a follow-up on her work that falls within the so-called “feminine arts”—collage, costume and textile designs.

Alicja Rosenblatt was born in Kraków in 1889, the eldest daughter of a wealthy Jewish physician. Artistically minded from a young age, she studied at the School of Fine Arts for Women in Kraków run by Maria Niedzielska. She also took private lessons in drawing and painting from the best Polish painters: Wyczółkowski, Weiss, and Pankiewicz. From there she went to study painting with Simon Hollósy in Munich, before moving to Paris in 1912. At this time, she changed her surname to the fabricated Polish “Halicka” to rhyme with her given name and, according to historian Paula Birnbaum, possibly to hide her Jewish roots. In Paris, she studied under Maurice Denis and Paul Sérusier at the Académie Ranson. In 1913 she married fellow Polish émigré Louis Marcoussis, who had earlier changed his name from Ludwig Markus under the recommendation of Guillaume Apollinaire. Due to France’s history of hostility towards Jews, the pair converted to Catholicism, were married in the church, and later sent their daughter to Catholic school—she was not told of her Jewish heritage until the eve of World War II. Halicka did not even mention her ethnicity in her memoirs—published in French in 1946—though she recounted the atrocities of the war.

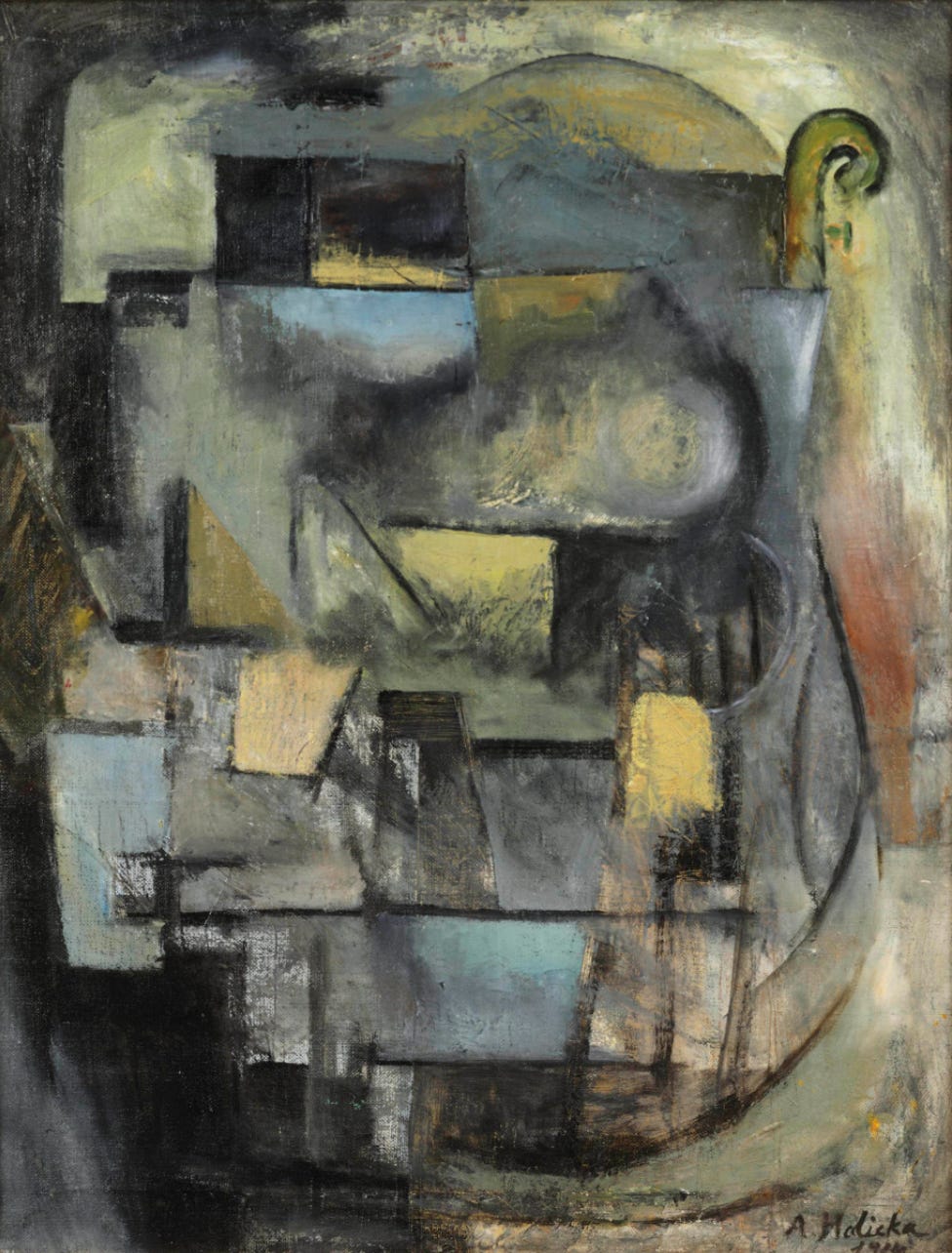

Both Marcoussis and Halicka’s careers were marked by this need to hide part of their identity—Marcoussis took on a French name and Halicka a more self-consciously Polish one (establishing her difference in nationality, not ethnicity) in an effort to pass within French society. As Birnbaum writes, “Halicka’s attempt to stake a place for herself at the center of Parisian avant-garde culture was made doubly difficult by her diaspora identity and her position as a woman within a traditional heterosexual couple. Whereas Marcoussis engaged consistently in a cubist aesthetic (which was itself associated with ‘Frenchness’) and often featured the Parisian landscape in his work, Halicka’s work shows much less confidence in her position within the Parisian art world.” When they married Marcoussis’ work was firmly cubist, a style she began to experiment with. Through Marcoussis she met Picasso, Braque, Apollinaire, and Max Jacob, but she was always aware that she was allowed to sit in on their gatherings only as a wife and muse—not as a painter in her own right. Though she showed a highly lauded cubist still-life in the 1914 Salon des indépendants, Marcoussis acted as a gatekeeper and prevented her from associating with his friends and fellow cubists. When he left to fight in the war and they were separated for five years, Halicka entered a period of intense cubist exploration in isolation. In a 1974 interview, she spoke of how he returned from the battlefield in 1919 and saw her new works only to exclaim, “one cubist painter sufficed per family.” Distraught, Halicka destroyed many of her cubist works and hid the rest in a friend’s attic in Normandy. The interviewer (a life-long friend of Halicka’s) stated that Alice was both “compliant” and “too independent” to continue to paint in the same style as her husband, and so she “changed her style and forgot her cubism.” After the war, her parents could no longer help her financially—Alice was forced to sell her jewelry, furniture, and even rugs to support herself and her husband.

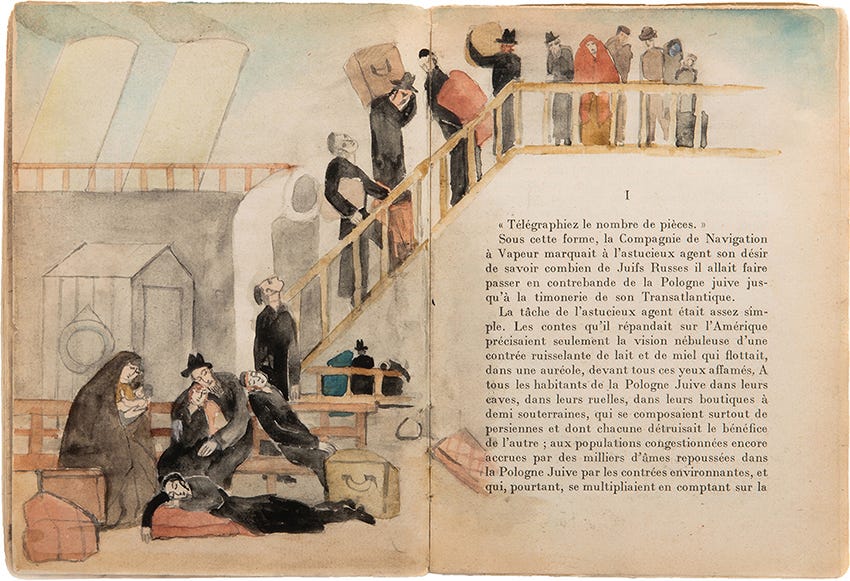

In 1922 she gave birth to their daughter. Since Halicka believed that Marcoussis should devote himself solely to his art, she abandoned her own painting for a period and pursued textile and wallpaper design to support the family. Abnegating her own desires for his, when she did return to painting her work was more overtly figural. In the early twenties, she returned to Poland on two trips. Against her parents’ wishes, she visited Kazimierz, the Jewish ghetto in Kraków—there she “produced a series of figurative works confronting the subject of the Jewish ghetto in Cracow.” Exhibited in several solo shows in Paris, these works served to further distance Halicka from her Jewish roots—she, like the bourgeois Parisian gallery-goers, was peering as an outsider into this world. Due to the success of this work, she received a commission to illustrate the French edition of Israel Zangwill’s Children of the Ghetto: A Study of a Peculiar People, the “story of Jewish immigrants recently arrived in London's East End trying to scratch a living in extreme poverty in the 1890’s.” Caricatures, the stereotypical Semitic features of the drawings reveal Halicka’s inner conflict between the Anti-Semitic world she wanted to belong to and “her own irrevocable Jewishness.”

“Always dissatisfied, I often changed styles.”

By the 1930s, Halicka had begun to paint sparsely inhabited Parisian landscapes. Among them was a series of monuments—Place de la Concorde, the Tuileries, the various bridges over the Seine. Interestingly, these were painted during several lengthy visits to New York between 1935 to 1938. One of her best friends was the fellow Polish-Jew Helena Rubinstein, the New York-based makeup mogul. Rubinstein hired Halicka to produce some of these Parisian scenes for an advertising campaign. With Paris the known center for fashion and culture, these romantic images lent Rubinstein’s cosmetics the proper gravitas and elite image. In late 1936 Halicka also painted murals in the health bar and treatment rooms of Rubinstein’s newest New York establishment—really much more than just a salon, one historian wrote of them as blurring “the conceptual boundaries among fashion, art galleries, and the domestic interior.” While there, Halicka had two exhibitions—in 1936 at the Marie Harriman Galleries (all Place de la Concorde watercolors and drawings), and another in 1938 at the Julien Levy Galleries. At Levy, she showed New York scenes as well as some collages, described by her as “quilted romances” (more on those Friday). A review of the cityscapes marks how, “Not for this lady are the stark machine-age outlines beloved by most contemporary artists; to her, the city has an opalescent loveliness and delicacy of structure.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, the first line of the review introduces her as Marcoussis’ wife.

Birnbaum is the sole historian who has interrogated Halicka’s life, career, and art history’s lack of remembrance of her. For Birnbaum, Halicka is one of a larger group of female artists working in Paris in the 1910s-40s that have been forgotten or glossed over in the hagiographies of their male counterparts. Her book, Women Artists in Interwar France: Framing Femininities “illuminates the importance of the Société des Femmes Artistes Modernes, more commonly known as FAM, and returns this group to its proper place in the history of modern art.” The Société des Femmes Artistes Modernes (FAM) was founded in July 1930 by the artist Marie-Anne Camaz-Zoegger; in her words, “with the goal of displaying, in harmony, the most beautiful works by the artists who are the most characteristic of the School of Paris… In forming the FAM I am attempting to present a group of artists truly committed to our great modern art from our modest, feminine cadre.” From 1931 to 1938, the group held an annual exhibition that prominently exposed Parisian society to female artists. Halicka’s painting and studies of Place de Ła Concorde (from 1933) were included in both the 1935 and 1937 FAM exhibitions in Paris, in addition to the group’s joint exhibition with the Women Artists’ Circle of Prague in 1937. With this painting, Halicka officially represented Poland in the 1937 Women Artists of Europe exhibition—held first at the Jeu de Plume Museum in Paris and then at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

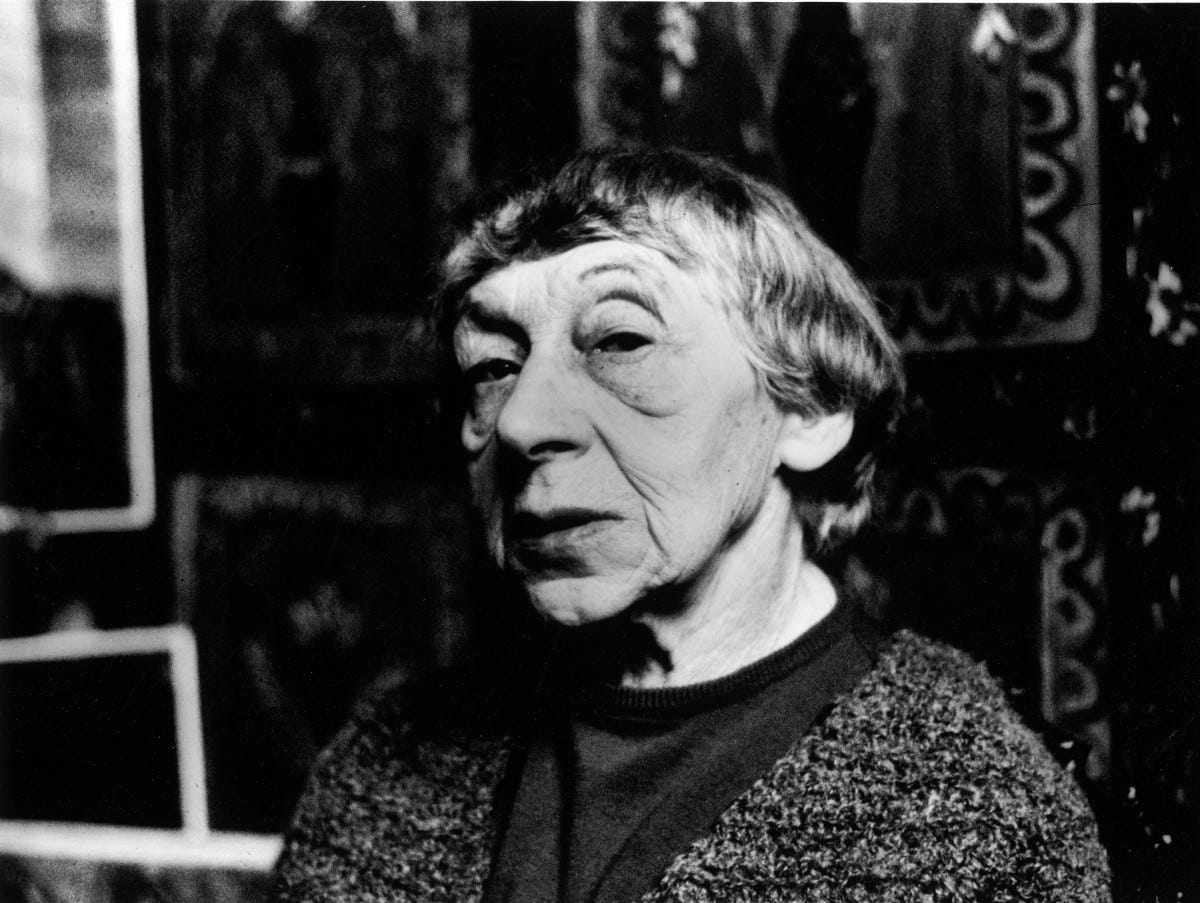

Against the advice of friends, Halicka returned to Paris in 1938 just as the war was arriving there. Soon after the final FAM exhibition in March, Halicka and Marcoussis traveled with their daughter to a village in the south of France, where he died of natural causes. Halicka and her daughter then fled France through the Alps, hiding out the war in Switzerland. After returning to Paris in 1946, she wrote her memoir Hier (Souvenirs), documenting her early childhood in Poland until the Liberation. Instead of featuring her own works in the text, she included her husband’s—further reinforcing the marginalization of her career to his. Fifty years after she destroyed many of her cubist works, in 1969 the ones she had hidden were returned to her. Sixty of these paintings were shown at a solo exhibition in Paris in 1973, the year before she died at age 85—finally, Halicka was given her due as a cubist painter in her own right.

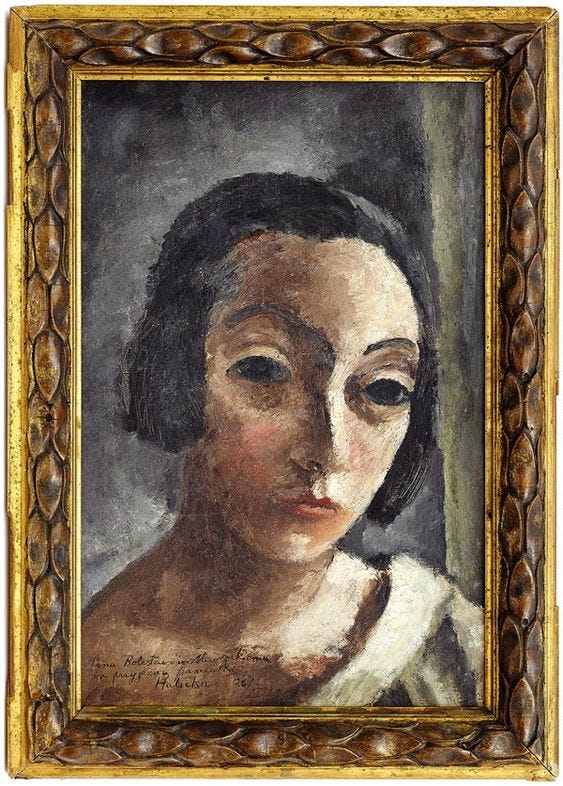

This analysis by Birnbaum is a concise and moving perspective on Halicka: “She tried to evade her essentialization as a wife and mother by Marcoussis by making cubist paintings; yet they are always within the parameters of her more conventional bourgeois marital relationship. Halicka’s husband discouraged her cubist practice, and this led her, tragically, to ‘efface’—the artist’s own word—much of her early artistic practice. Consequently, in searching for a viable artistic identity, she frequently shifted styles and aesthetic interests, Whereas Laurencin’s figurative version of cubist painting, consisted throughout the 1910s and early 1920s, was classified as avant-garde by some critics, Halicka’s more deliberately abstract cubist enterprise was not always taken seriously by the press. When she added vibrant colors or evidence of figuration to her cubist still-life paintings, some critics read femininity and lack of academic rigor. In the end, Halicka publicly blamed herself for her lack of critical recognition… One thinks back to her early self-portraits and can only imagine all the ambition and desire that the young, newly-married artist suppressed over the years in order to support her husband’s career.”

Halicka hid her heritage and went against her best interests to uphold the beliefs of the Parisian art world and her husband. In doing so, she allowed herself to become a footnote in other’s stories—the stories of more famous men. Due to her desire to be respected by the avant-garde, she emphasized her paintings and minimized her other, more feminine work—which, as I believe you’ll understand after Friday’s paid subscriber email, was the more important and innovative.

Further reading:

Marie J. Clifford, “Helena Rubinstein's Beauty Salons, Fashion, and Modernist Display,” Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 38, No. 2/3 (Summer/Autumn 2003).

Paula J. Birnbaum, “Alice Halicka’s Self-Effacement: Constructing an Artistic Identity in Interwar France,” in Diaspora and Visual Culture: Representing Africans and Jews, ed. Nicholas Mirzoeff (New York: Routledge, 2000).

Paula J. Birnbaum, Women Artists in Interwar France: Framing Femininities (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2011).