Fitness, and the pursuit of the body beautiful, have become such a vital part of American culture—and such a constant presence in media, advertising and retail—that it is difficult for many to imagine that it wasn’t always this way. That in fact, exercise has a relatively short history in the US—one that historian Natalia Mehlman Petrzela clearly explicates in her new book, Fit Nation: The Gains and Pains of America's Exercise Obsession, which is available for pre-order now (releasing February 2nd).

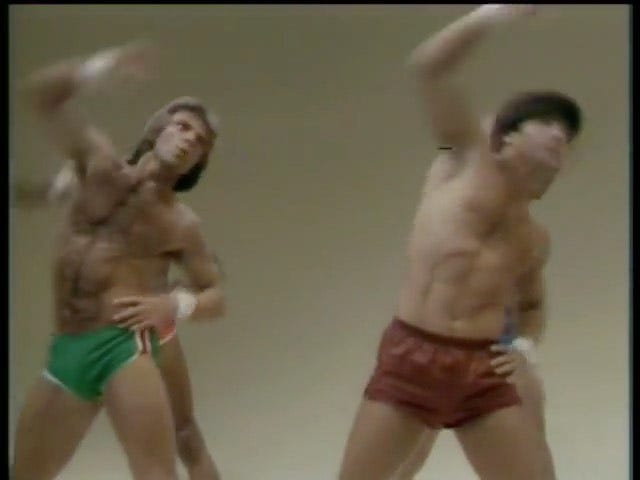

As someone personally obsessed with exercise and long fascinated by past trends in fitness (just check out my hashtag on Instagram, #laurakittyworkout), I’ve always been on the lookout for scholarship on the subject. I first came across Natalia’s writing in 2015 when she wrote a series of articles on fitness history for the wellness site Well + Good. Since then I’ve followed her career from afar—in addition to teaching at the New School, Natalia is the cohost of the Past Present podcast and was the host and co-producer of the truly wonderful podcast on the Chippendales, Welcome to Your Fantasy (check out their workout video below).

In Fit Nation, Natalia takes us from late 19th-century strongmen to reducing salons, Jack Lalanne, yoga and Esalen, Jane Fonda, Richard Simmons (more on him next week), Peloton, and everything in between. Scholarly, well-researched and easy to read, she takes into consideration how all of these trends and developments in fitness operate within or in opposition to American culture as a whole—complexly analyzing how race, gender, sexuality, size and ability come into play in “America’s exercise obsession.” Natalia is also a certified fitness instructor, providing an extra layer of intimacy and understanding to her analysis.

Natalia and I spoke last month—it’s a long interview but I think a valuable one. Our conversation snaked all over the wider subject of American fitness—covering the background of this project, previous scholarship on this subject, fitness in the public vs. private spheres, the exclusivity of fitness, gendered workout spaces, fat aerobics, her research and her hopes for the future.

You can learn more about Natalia at her website. She can be found at @nataliapetrzela on Instagram and Twitter.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Laura: I’d love to know how you decided to do this book, as you wrote that you've been working on it for 10 years.

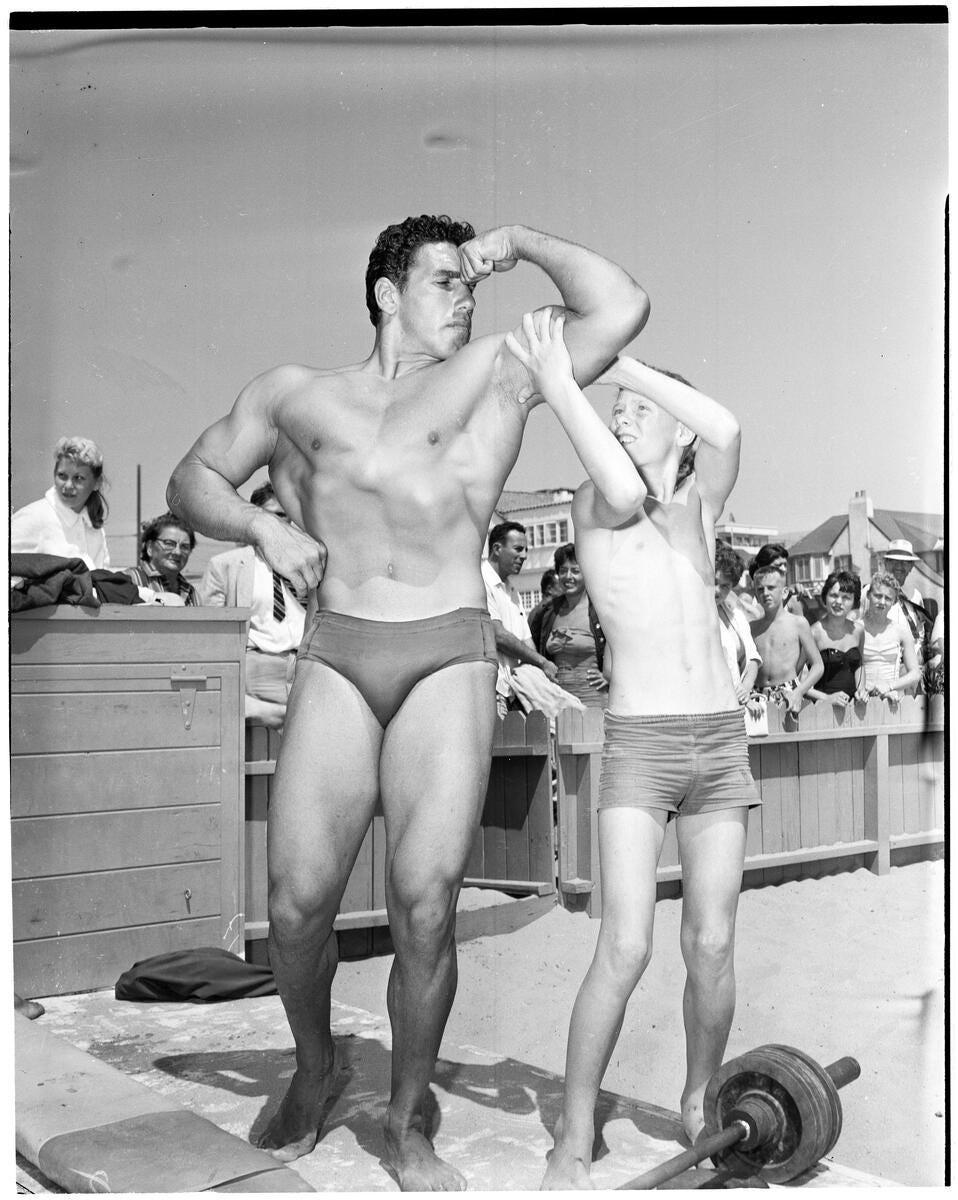

Natalia: In some ways, I have rather conventional intellectual training. I have a PhD in history. I'm really focusing on politics and culture of the US. And my first book was about cultural conflict over education. It's called Classroom Wars. I was a middle school teacher before I went back to graduate school—what is the bulk of our experience when we're very young? It's having been in school. So, it was really invested in all of that. Now, I was in graduate school in California, and the bulk of that research had me looking at California in the 60s and 70s. So, one of the first things that I just sort of got interested in was looking at kind of like the broader world of California in the 60s and 70s. And of course, that's not just what I was looking at for Classroom Wars, which is kind of the collision of left-wing politics, right-wing politics, but it's also the New Age. It's also Muscle Beach. It's also Jazzercise. And so, I was studying the milieu that all of this came from, and already kind of intellectually interested in and somewhat conversant in that context. Now, that was all sort of in the background.

But I also always had this kind of double life as a gym rat and as an intellectual, and to be quite honest, especially as a feminist, I was really conflicted about that, because it seems to me that this world that I love so much of the gym, I kind of knew it was kind of an engine of the patriarchy, yet why did I love it so much. It was also kind of seen as intellectually unserious. That being said, once I got Classroom Wars off my plate, and I was also at that point teaching fitness, I was so compelled to kind of study this world of fitness that I love, but also saw as deeply problematic, and also didn't see a lot of scholars taking seriously.

I will say, there was one moment I was walking in LA, and I looked up and there was this gym. And there was a row of treadmills, as gyms all over the world have, and all these joyless people were booking it on the treadmill, quietly looking straight ahead. And I just was like, “What a strange thing in our culture, people pay so much money and spend so much energy like working really hard to go nowhere, like, what is that kind of all about?” So, there's both through my own experiences in the gym as an exerciser. But also, you know, seeing it a little bit from the outside.

How do you think that being a fitness instructor influenced the way you approach this project?

I think that there obviously have been scholars that have studied this stuff, and some of their work is phenomenal. I stand on their shoulders in many ways. On the other hand, some of it, I think, has a kind of clinical detachment of like, "Oh, I am like this expert and this intellectual who's studying this very nonintellectual world," which is totally a part of the gym. Now, the gym is a place where, as an instructor, and I was a front desk girl—I really like have been in that world for a long time. And so, of course, that raises some questions of bias and positionality. But on the other hand, this is a world that I know from the inside, and that I really respect. And so, one very concrete way is that it allowed me to have a lot of contacts where people trusted me and so I could say, "Oh, do you know anyone who was around when Tae Bo launched?" and someone’s like, "I know the producer of those videos," and I could get in touch with them. And I did think really hard about any kind of bias and correcting for the fact that in some ways, I am an insider, but for the most part, I hope I did a decent job with that. And I am eternally grateful for the kinds of contacts and inside track that I got because of that connection.

I think it does come across as unbiased. Having read some of the other books that you're probably talking about, like Shelly McKenzie’s Getting Physical: The Rise of Fitness Culture in America (2013), your book definitely felt less detached and less impersonal. One of the other things that I noticed in comparison to McKenzie or Jonathan Black (Making the American Body, 2013) was that it felt like you were really talking about how fitness had become an individualist endeavor that takes place primarily in the private sphere, and you were really concentrating on that—which was an interesting analysis for me.

Thank you. Both McKenzie and Black's books were definitely important to me. They are different in a range of ways. But yes, one of the things that I think that I contribute, and sometimes it comes from the fact that I'm writing several years after both of them, is we have so much more attention to inequality in the country right now, and the role of market dynamics and privatization in perpetuating inequality—and the gym to me is such an example of that. I can look at some of the same phenomena that some of these other historians have looked at, and to me, one of the most remarkable things is that we've had this huge expansion of the fitness industry. And that is a kind of a chicken and egg situation. It comes with a sensibility change where we think exercise is so important, and it's so good for you—and therefore people will spend money on it and there's a huge industry.

At the same time, we are disinvesting in physical education and in public recreation spaces. And yeah, there are a million green spaces in the West Village, near where I am right now. But that's already an affluent area—what about all the parks that are unsafe or not well lit, or where people don't even have the jobs to be able to have that flexibility to exercise? And so that was really important to me as a contribution to not just historiographically distinguish myself from what's come before—you can always fill a hole, find a hole to fill—but really, because I think it's so important in fitness too because there is such powerful language of bootstrapping individualism that permeates all of the fitness industry. I understand why that's appealing. And it can be kind of true, because you need personal motivation to get out there and exercise. But that discourse totally papers over and I think obscures these real structural obstacles that don't permit everybody to have equal access to exercise. So, I wanted to tell that story too.

Do you feel like there was a point in time when it was more of a part of the public sphere? And more money was actually being funded to it?

That's a great question. To be honest, I think there was no golden age—a lot of people, especially these Phys Ed boosters look back to the Kennedy years. And they're like, "Oh, that was like the best time." And it's true that JFK, and Eisenhower before him, invested a lot of energy in celebrating exercise, and they had these showpiece PE programs that really were super impressive. There was real cultural impact of those changes, for sure. But you know, those were mostly PR campaigns, like when you really dig down into the sources, the way that I did—there were all these conferences where they bring local officials, and sometimes sort of celebrity figures, to come and promote the fact that locality should invest in building these programs. So, it's not like there was ever this golden age.

I should say that even in the programs where there was good investment in infrastructure, and great buy-in to this stuff, those programs themselves were actually very exclusive of a lot of people. And I think that's something important to realize, too—that the golden age of Phys Ed under JFK, that's the Phys Ed that a lot of people, if you talk to them today, older people were totally traumatized by: "Oh, my God, the Presidential Fitness Test, I had to climb that rope in front of people, they put me in the button/the shorts that showed I was a lower fitness level than other people." Even the apex of national attention to physical education in this country was never really that great. So, I think there were seeds, there have been seeds of some really great stuff, but we can continue to cultivate those. But I would really caution against thinking there was ever a golden age in terms of this issue.

It was something I contemplated when I was reading your book because you didn't actually mention a lot of investment in building anything. Now, we always talk about how everything has been closed; we say, “Oh, they're closing all these public parks and public pools,” but was there ever an era when more of those were being built? And more money was going towards that? Beyond the New Deal?

Well, the New Deal definitely had pretty robust investment in public infrastructure, no question. There were relatively impressive facilities being built in the 1950s and 60s. Swimming pools, for example, were totally segregated. So, it's important to realize there was public infrastructure to an extent and investment but other forms of exclusion still existed. The other thing that I think is relevant in terms of thinking of—if there was not a golden age, there at least was less inequality in this regard—is the fact that what you have today of these super elite spaces, boutique gyms, private trainers, places that are like luxury hotels for fitness basically, as opposed to a sort of poorly funded PE class—that disparity didn't exist.

When I interviewed the founder of Jazzercise, and then her daughter who is now the CEO of Jazzercise, one thing that was really interesting that they talked about was the fact that when they started out—and that was like a really trendy place to be—they were in church basements and school gyms and not these kind of luxurious spaces. They said nobody expected luxurious spaces to exercise at that point, particularly women who were not really included in the gym culture at that time. So, I do think that the presence right now of this super elite boutique space and these really fancy health clubs, like that almost exacerbates this sense of inequality today, and it's not just a sense, it's real.

Yeah, that’s definitely something I've been watching and I'm very aware of, as someone who's more of an at-home exerciser. Whenever I do sort of venture into those places, I'm like, “Wow, I don't even feel like I belong here.” And I'm probably closer to the person who should belong there, you know, but they are so elite feeling that it’s exclusionary.

I think that you're right. And I think that that functions in a variety of ways. One of the things that I really tried to do with this book was to be precise about what kinds of inclusivity and equality that I'm talking about, because the same old categories structure everything in our country—there's class, there's race, gender, etc. But depending where you're looking at it, fitness—certain categories of identity really loom much larger in terms of this issue. So, one thing that I've realized, just in my own experience, kind of like what you're talking about—I mean, I should feel good in basically any fitness environment, like I know that world, I sort of look the part, etc. But it's interesting being in this world for a long time, I'm 44. And I actually just came from a workout at a studio that shall remain unnamed, and I feel kind of old there. And it's fine, I can do the workout and I'm perfectly capable of doing it. But I definitely have been in this long enough that at those kinds of studios that sort of privilege the young hot, cool kid, I'm like, “I'm not that anymore.” And when I was that, I didn't even realize that that was being privileged because it was normative.

And that kind of realization, always encourages me to really open my eyes and think about what else is unexamined in fitness, particularly size, right? Especially in places like New York and LA, which have long been hotspots of the fitness industry. If you're a larger person that in itself is like, you can feel like a sore thumb, right? Race, of course... physical ability. I mean, that's a huge change that I chart—one of the things that's really fascinating is that for much of the history of the fitness industry, there was no presumption that disabled people would even want to exercise. There was this one case where some gyms were sued, because they were not accessible to people with disabilities. And the head of the trade association, basically, is like, “No, they weren't being explicit, they just did assume somebody who was in a wheelchair would even want to go into a gym.” And I think that's a really interesting shift over time that now people do. People of every sort of identity category want access and purchase and to feel sort of included in the world of fitness. And sometimes that means militating for accessibility to existing places or creating their own. And that's really interesting for something that was basically a niche subculture for a really long time.

Through the book, you chart the different sort of spaces where fitness takes place, and they're very gendered for most of the 20th century. Do you think that they're still really strongly gendered or has it become less so?

I think that these spaces have become much less gendered, like there's so many mixed-gender fitness spaces, absolutely. And even there's some that pride themselves as being sort of like meat markets, right? There are all these posts about CrossFit weddings and whatnot. I should say that that is because a lot of the social assumptions about the impropriety of men and women working out together have fallen away. So earlier on, like in the 1960s, they had these sex-segregated spaces, ladies’ days—there were ladies’ gyms, etc. And of course, that was because there was this presumption that it was gross for men and women to mix or improper—improper particularly for men to see women sweating and wearing these tight-fitting outfits. That changes a lot for kind of obvious reasons: feminism, changing attitudes about gender and propriety, and whatnot.

But I think one thing that's really important is that there are still, especially for women, a lot of predominantly female exercise spaces. And it's interesting why those exist. And I think that there's a lot of variation there. I think that some of them are very deliberate, and that is because some women seek a space where they don't want to be ogled, and they want to be just in the company of other women. And they just kind of want that experience, which is—if not quite feminist, it is a kind of like liberation from the male gaze, for lack of a better term. And there's some places that are very self-consciously that. There's a piece that I mentioned in there about some women in Los Angeles, Latina women who have a Zumba operation. For them, it's like being able to go to the club and dance without men they don't want grinding on them. I thought that was really powerful. And also, not to have their boyfriends and husbands be jealous of like what they're up to dancing. Like they're just at Zumba class, right? So, I think that there's a kind of self-consciously women's only space.

But then there's also… it's been caricatured a lot but the fact that some of these, especially these luxurious spaces, tend to be the arena for stay-at-home moms to spend time together and to tone their bodies while their husbands are at work and their kids are at school, and I would call those probably less deliberately feminist spaces, but still predominantly female ones. And then there's a lot in between. I wrote this piece in The Atlantic about Jazzercise and it continues to be a brand that just totally fascinates me, in part, because to me Jazzercise has always resided in between those two worlds, where it is very much this women's only space where women went and were told, “you can spend money on yourself and going to exercise and to dance and to just sort of be free—you don't have to sit on the sidelines while your daughter is dancing.” And I think that that's great. On the other hand, that brand came about in the 1970s. And certainly, at that time, it was not what we think of as your textbook 1970s kind of feminism, right? It’s not only a weight loss program but it was definitely billed as a sort of slimming program. Most of the women who were involved were married straight women, it kind of grew into this incredible franchise operation which is basically still all run and populated by female franchisees, but it's very much that kind of entrepreneurial female—I don't want to quite say Girlboss-ism, but like a little bit. And so, I think to me, that's such an interesting example of a fitness space that is deliberately female, but that doesn't quite fit into any of the categories that we tend to think about in terms of those spaces.

And it's also deliberately nonelite, right?

Yeah, deliberately nonelite. I mean, very different from the kind of glitzy big city gyms like the Vertical Club or, like in LA, the Sports Connection—all of these places which were glamorous. Jazzercise studios were mostly suburban and they were meant to be kind of approachable and welcoming to all different kinds of folks. And they all didn't have mirrors in them either, because the founder realized that they made women feel self-conscious. That's a huge deal because there are a lot of other studios where so much of it was seeing yourself and the kind of performance of it all. And I think that can be empowering, too. I write about Molly Fox's studio, which was all about the mirrors and feeling the sexiness of it.

On the issue of the mirror, I read all, I think, of the scholarship on this issue, and one article, which is both scholarly and a primary source, is by this film critic, Margaret Morse, in the 1980s. She comments something very interesting—one: she wants to look at, analyze these fitness videos because she's so obsessed with aerobics videos herself, but is like, "I want to understand this a little more." And one of the things that she talks about is the not quite mirror image of watching the instructor and mimicking her. And it's like an image of yourself, but more perfect and just out of reach. So, there's the sense of like, "Oh, I'm doing what Jane Fonda is doing. But my arms aren't quite as nice as hers. Maybe if I keep going," and of course, with this new VHS technology, you can just rewind and do it again and do it again. I'm really interested in the use of mirrors and the way that they can both be a really important empowering part of the experience. But also, I think, for some, not so much.

How do you think that that sort of mirroring the instructor applies to all of the streaming platforms now?

That's a really good question. Probably not all that differently from the VHS days, although there's just such a variety now of people that you can choose from. And there are, I would say, just so many more body types and approaches, that's something that actually, I think, is really positive in terms of the direction that things are going; if you think about the production process of fitness videos, it used to be they were these big budget productions. And there were a few people who dominated the category, and that is what you saw. And then now the fact is that you have all these YouTube people and Instagram people, et cetera. I mean, on the one hand, it's a little bit more aggressive, because there's fitness content everywhere all the time. But you have people who would have never gotten a contract with Sony, or with Gaiam, or whoever, who end up being incredibly inspiring. And so, I think that's a really positive change. People are always like, so has it gotten better or worse? I would say that is one of the things that has probably gotten better.

What were some of the more surprising things you came across in your research?

I should say, first of all, I did a lot of primary research and relied on the scholarship of so many others. And so, I first want to shout out one scholar who really educated me a lot, Jenny Ellison, who writes about fat aerobics. I did not know that there was this whole movement of fat aerobics instructors during the 1980s, who were basically creating aerobics programs for fat women at the same time that Jane Fonda and Jazzercise were doing the same for not-so-fat women. And one of the things that I found so interesting in Ellison's work and also the primary work that inspired me to go do is the variety of approaches that women in these businesses took towards fat women. It was, on the one hand just straight-up radical for fat women to say, “we're going to start an exercise business and we're going to cater to fat people.” And some of it was very much in the idiom of fat acceptance and the fat liberation moment of that period. Some of it. All of it was radical, some of it was in that idiom.

I was really taken by the fact that these fat women—who were out there with their leotards and wanting to look like the people that they were catering to—they were so fat phobic, I guess in the terms that we would use today. They would tell their instructors, "you can't say the word fat," they would say, "Oh, we're fluffy ladies"; they would insist that instructors had a full face of makeup and have a pastel color palette of the very traditionally feminine leotards that they would wear. And they would give awards for weight loss and all the rest. I think that that's such an interesting and sort of surprising piece of fitness history because one, we don't tend to hear it at all—how many profiles have you read about Jane Fonda's Workout and you don't hear about that [fat aerobics] at all. And it both speaks to a kind of radical past we don't know about it, but also a very different definition of radicalism that was possible at that time, and so I think that it's those sorts of things that I find surprising and really compelling.

Where are archives for all these different things? Are they actually real archives? Or is it just someone's box in their closet? You never know with sort of untraditional, less studied subjects.

All of the above. One of the things that I did, especially with the Phys Ed piece, is that I both used the SHAPE AMERICA archives, which there are some in-person holdings, but I mostly use their virtual holdings. Every time I would be on a campus doing a talk or something, I carve out half a day to go to their special collections. And just be like, what do you have on recreation? What do you have on women's fitness? What do you have on your student intramurals? And I would try to dive into those archives. I spent a good deal of time at the NIRSA archives in Oregon, which is the National Intramural-Recreational Sports Association; that was super interesting in looking at the early 20th-century creation of these campus cultures around recreation, not sports. I got to go to Nike, which was such an amazing experience. They have a big digital archive, but I also got to see some of their archives. Because of the pandemic very sadly, I could not go to University of Texas, Austin, where there's an incredible physical culture archive—I used some of their online holdings.

I was just so lucky to do a lot of oral history interviews, and also to have access to some of the holdings of a lot of the folks who I spoke to, and that was really just invaluable. Leslie Kaminoff, who's been in the kind of yoga space for decades—he's also, thank God, just an archival rat. He had like every promotional poster that he made, every letter that he wrote, and he was just so generous in sharing that all with me. So, you're right, it's a nonstandard kind of archival journey. And there's no accident in the fact that when I'm doing the PE part of it, there are documents because there were PE departments. And that happened on campuses, and there was national and federal policy around that. And so that stuff is like a lot more documented in the conventional sense of what a historian looks for. But the other stuff particularly because it was individuals and private companies, it was a lot of catch-as-catch-can in terms of just doing the best I can. I tried to both be declarative in my statements—and I'm covering a lot of time and like a lot of space—but also to be appropriately humble about the limits of what any book that's covering over 100 years and a national story can do, because obviously, I couldn't look at everything, because that would take a lifetime. But, as you know, it's hard to do that as a historian, right?

When you were doing especially the PE part and the intramural part, how much did that connect with the work you did for your first book?

Significantly. I really started in the history of education world, so I had a really robust network of folks who I could draw on to kind of ask questions about Phys Ed and about this curriculum. And of course, one of my elective fields for orals when I was doing my Ph.D. was history of education. There's actually not that much written about PE so I think I like read every major book already about that at the time.

I also would say one of the things that was interesting to me is when you asked, was there a golden age? I don't think there was ever a golden age. But it was kind of remarkable that in the 1960s and 70s, and really even kind of into the 80s, a lot of the people who were a big deal in the private fitness industry world, were also doing all of these public events, like they were working with the University of California system, they were doing all these youth events, they were doing workouts on the White House lawn, and now, I feel those worlds are much more separate. Yes, there are these kind of splashy charity events that some big brand does. But it seems almost like the big fitness celebrities, like some of the big Peloton instructors, as much as some of them are quite social justice minded, they're not designing PE curriculum in schools, right? And I think that that is different from what we saw in the 60s and 70s, and even into some of the 80s.

That makes a lot of sense. I collect fitness books by just anyone I come across. And I do you feel that, in these books by people who are lesser known today, there's sort of a broader look at what children or the elderly should be doing—much more gendered than it would be today—but they're sort of looking at all of life in a way that I don't always feel that people are talking about it today.

I think that's right. And I think that some of that comes from the fact that in this earlier era, particularly for women, but somewhat for men too, all the types of people who were interested in this kind of work, they would have been PE teachers, if the fitness industry hadn't blown up when it did in the late 70s and early 80s. I cannot tell you how many people told me that. I cite one who said it best, Tamilee Webb, Miss Buns of Steel, who's like, "I would have been a PE teacher," and I think that that is just so remarkable to think about how the accident of one's birth really changes the course of one's life. There are a lot of other women who I spoke about exactly of that age, a lot of them who were able to play sports in college because of Title IX, which was obviously unheard of before the early 70s, and then—who by the time that they were going out into the world, when they would have been PE teachers, which you know, no shade to PE teachers, but it's a very different kind of track—there was this industry where they could go and make money and become celebrities, and make videos and all of this stuff. That is just really something that was a bit happenstance of that period, but it really speaks to the uniqueness of that era. But to get back to your original question, I think that that is part of why a lot of those people are talking about youth fitness and thinking about children. And also, there was always a conversation, certainly since the 1950s, about the crisis of youth fitness. So, that was kind of a way almost to sell the import of your work.

Based on your last answer, do you think there are people that would have gone into PE now trying to be influencers? And is that causing there to be less teachers going into PE?

There are definitely less teachers going into PE. It's a profession that's a little bit in crisis. I can't tell you, "Oh, this one would have gone to do this, and she wants to do something else." My sense is, though, that if you are someone today who feels like your career lies in fitness, sadly, because of the poor compensation and the poor cultural esteem of a Phys Ed teacher, that's not the path that you're going to go on. There are incredible PE teachers out there, but I think more of them are really motivated by a desire to work with children and to be educators more than to be fitness celebrities because that is not the way to come up as a fitness celebrity today. And it never really was. You know, it was just the way to make a living. Now there's just a way to make a living and more than a living—not as a PE teacher.

But that said, for all the glitz and glamour of being a fitness instructor today, most fitness instructors do not make a lot of money. And I think that's something that is often kind of obscured when we look at these profiles, "the SoulCycle instructor makes three-quarters of a million dollars." It's totally a superstar economy, right? They're definitely these individual people who make a lot of money. And then there are a lot more than that who have really formidable online presences and have a kind of mystique about them, and then there are many more people who really are total gig workers and have a really rough time making ends meet and are compensated by the number of people in their class and can't afford to live in the neighborhoods where they teach, don't have sick leave, and have to project that they're living their best life on social media 24/7 because that's what a lot of people are buying. And I think that that sort of labor of the Fit Pro is so unexamined, and is really, really important to understanding the full picture of what's going on here. Often we focus on consumer emphasis or the CEO, but not so much the people that are doing the work.

I thought it was interesting when you were touching on in the book the various attempts to unionize as fitness instructors. And basically, it seems very difficult.

I think it seems difficult because it's difficult to unionize, period. But there are, of course, aspects of this work that make it even more so, like I mentioned in the book, people tend to be diffuse and working in lots of different places. Less so now, but I think it's still the case that a lot of people think of teaching fitness as a side gig or something they're doing on the way to something else, even if maybe they end up staying with it. So that can forestall unionization. And then I think this other piece, which in some ways is the most culturally interesting is if you are a house cleaner, or a chambermaid, you know, you're working in the street, a construction worker, there's no mystique to that work—you can say, "this is really hard work, and I'm getting sick" or "it's really tough, and I need to be compensated because my joints hurt and I have these problems." If you're a fitness instructor, you're supposed to be the picture of health and wellness and abundance and affluence. So, to even articulate those complaints about your life presents, I think, a professional and kind of reputational risk that I understand why a lot of people don't want to take.

One of the reasons that fitness culture has become so powerful is because it has become about so much more than the physical, and it has become so interconnected with self-help culture. I think that that ideology of, “if you're not wealthy, then you must not be working hard enough,” or “you don't have an abundance mindset” —it's the kind of thing you hear in fitness classes, and for an instructor to say, "I'm not making enough money or I'm injured, etc." It's like, "oh, are you not practicing the law of attraction?" I say this with a laugh, but I think that all of that is pretty insidious in perpetuating a lot of the inequalities around the labor that happens in fitness spaces.

There was a quote in your conclusion: "With each public Physical Education Program cut due to austerity, every basketball hoop removed in the name of public safety, every unexamined juxtaposition of unlit street and shattered community center with expensive commercial gyms and connected fitness devices, we squandered an opportunity to address the widening fitness gap that divides and defines a policy that largely agrees on the value of exercise." How do you think we can work to redress this gap?

I think that the good news in that long quote is that pretty much everybody agrees exercise is good for you, and that people should do more of it and have the opportunity to do more of it. And so, let's just pause there, it's rare to find something that pretty much everybody agrees on. So already, I'm optimistic about that. From there, I think we have to keep reminding ourselves and each other across the aisle, that we all agree with this, so what are the policies that need to be in place for people to be able to participate in this Fit Nation? To me, that probably looks like some things that are probably thought of as characteristically left, like more funding for PE and public schools and for public works projects. But on the other hand, there are other things that are not so partisan. I mean, that's probably also going to be funding youth rec leagues. I mean, that's as American as apple pie, right? That's also creating more green spaces in cities and better-lit streets—that's not exactly a far-left proposition. Also, from a policy perspective, it would mean building incentives into health plans so that if people join a gym, they get a break on their insurance premiums. Some of those things are really not partisan at all, and hopefully we should all be able to agree on. So, I think the answer to that very much begins with policy.