Finding Ella Briggs: On Modernism, Women Architects, and New Approaches to History

Despina Stratigakos and Elana Shapira on Their New Book

How do you research an architect who worked across countries and continents, through wars and societal upheavals, whose work was undervalued and often unseen? Especially if that architect was a woman—someone whose sex delayed their education and brought them less work—and a Jew—whose race led to their fleeing their home, archive, and the career they had spent decades building? That’s the puzzle historians Despina Stratigakos and Elana Shapira set out to solve when they decided to reconstruct the life and career of Ella Briggs.

Ella Briggs (1880–1977) was a talented architect, designer, and writer whose influence was felt on both sides of the Atlantic. She trained with the Viennese Secessionists and brought their radical ideas to Gilded Age New York. She designed modernist housing for the masses in Austria, was jailed as a suspected spy in Mussolini’s Italy, and thrived in Weimar Germany before suffering persecution under the Nazis. Fleeing to London, she contributed to England’s postwar reconstruction. Yet despite a long and prolific career, her name is largely forgotten today.

Both Stratigakos and Shapira had separately spent time researching Briggs, and knew of others, but due to the peripatetic nature of Briggs’ life, their individual findings were patchy and incomplete. Several years ago, Shapira organized a symposium of everyone who had studied some aspect of Ella Briggs’ career, and from that grew the idea for a new kind of biography—a collaborative one, where a large group of historians and researchers worked together, in different countries and languages, pooling their knowledge and discoveries. Working over Zoom, a team of sixteen wrote Finding Ella Briggs, which was published a few months ago by Princeton University Press.

The Ella Briggs that emerges is fascinating. A woman ahead of her time (yet very much bound by the gender rules of the societies and cultures she lived in), perpetually looking forward, continually reappraising how modern architecture can better serve its inhabitants (not something that can be said of most male modern architects).

Equally fascinating for me was the collaborative approach Shapira and Stratigakos took in the creation of this book; I found it inspiring talking to them about the nitty-gritty of working with so many other historians and the joy they found in it. I spoke to them over Zoom two weeks ago. Our conversation swirls around ideas of women in architecture (something Stratigakos dissects in an earlier book, Where Are the Women Architects?), modernism, social housing, the difficulties in researching and writing such a complex story, and much more.

Elana Shapira is a cultural and design historian and lecturer at the Cultural Studies department at the University of Applied Arts Vienna. She has organized and co-organized international symposiums and workshops on the topics of Austrian émigrés in the United States and in Britain, the cultural legacy of Viennese modernism, Jews and cultural identity in Central European modernism, and women artists, designers, architects, and patrons. She is the author and editor of many books and edited anthologies, including Style and Seduction: Jewish Patrons, Architecture, and Design in Fin de Siècle Vienna (Brandeis University Press, 2016), Gestalterinnen: Women, Design and Society in Interwar Vienna (De Gruyter, 2023), and Designing Transformation: Jews and Cultural Identity in Central European Modernism (Bloomsbury, 2021).

Despina Stratigakos, SUNY Distinguished Professor in the Architecture department of the University of Buffalo, explores how power and ideology function in architecture, whether in the creation of domestic spaces or of world empires. She is the author of four books. Hitler’s Northern Utopia: Building the New Order in Occupied Norway (2020), Where Are the Women Architects? (2016), and A Women’s Berlin: Building the Modern City (2008).

Laura: Thank you for taking the time to talk with me, and congratulations on the book. I found your process really fascinating as a historian who’s worked on lots of projects. To start, I would love for you both to give brief introductions to yourselves and your backgrounds.

Despina Stratigakos: I began my interest in our artistic material world through anthropology, being interested in cultural expressions, and that has carried through into my world as an artist or an architectural historian, but I’m also interested in the cultures of things. The cultures of professions like architecture, for example, or the cultures of academia. I’m always taking this dual lens of looking at things, taking a step back to look at how people make meaning through words or art or in other ways.

Elana Shapira: I am a design and cultural historian and I work in Vienna for many years. I am interested more in Viennese modernism and its development in Vienna and beyond Vienna as part of Central European networks, and especially how it evolved in different countries after the Nazis came into power in this area in Europe. This is my somehow departure point also for the research on Ella Briggs. Then, also it came that we had a series of symposia on women designers, Gestalterinnen, [where] we had women crossing borders, and many aspects to the story that Ella Briggs actually somehow mastered. She’s a role model of many others who followed her.

Laura: How did you first learn about her?

Despina: This goes back to my curiosity about how we make meaning and the histories that are written or not written. I’m very drawn to the histories that are not on bookshelves. Ella Briggs has been this figure once at the center, but in the last 50 years, on the margins of modernist history. No significant writings or really no books about her. Very few articles, some important student theses. She was someone who modernist historians interested in Vienna had heard about and were curious about for a long time, but people had really struggled to write her history. It was incredibly difficult to write about her. I encountered her as a graduate student and started to research her. Like other historians before me, I ended up being defeated by the challenges of writing about a person like her, who was involved in so many different realms. Who was always moving, always absorbing new cultures. This book is coming back to a question that I couldn’t solve 30 years ago.

Elana: I was working on many women designers as part of an Austrian Science Fund project until 2022. I came across Ella Briggs as part of this project. Then I came across Despina’s research. I started asking, “Where is Ella Briggs? Who did research on her?” I knew all the people in Vienna, but Despina also worked in the United States. She had access to relatives of Ella Briggs. That was great as part of the research.

For me, it was a question: “How come she disappeared? In what way did she come back to the discourse in Red Vienna?” Especially for her social housing, [like the] Pestalozzi‑Hof (a large housing complex in Vienna). The issue was that she is the second woman out of—there are different numbers given here—but 150 men architects. It was Ella Briggs and Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky. Then I started speaking with other colleagues in Vienna, and each one of them had his curious anecdote about Ella Briggs. One said, “Oh, she was a spy in Italy.” The other said that she was also a spy in Eastern Europe. They came up with all these myths. I said, “Well, we have to break this, going around retelling anecdotes.”

Then we collaborated on a workshop at the Architekturzentrum in Vienna, which is the Austrian Architectural Museum. We had to ask several critical questions. Despina really wanted the woman histories here, woman-to-woman architects. She had a broader perspective on the subject. We wanted to actually change the narratives of the chronicles of Viennese modernism and Central European modernism through Ella Briggs’s personal story. So, we came together and we invited several people from Vienna who worked on her in different phases in her career. We asked also methodological questions: how are we going to approach a biography when we know that there are so many gaps in telling the story, still gaps?

Despina: Elana was responsible for getting us all together. When she reached out to me in 2019, we had this conversation where we slipped into this mutual reverie about, “Wouldn’t it be great to get all the people who would ever worked on Ella Briggs together in one room and see if we can finally piece together her life?” That symposium was exciting because it did get everybody into one room, which is rare for women in design. There are so many symposia about various important male figures all the time, right? It’s so rare to have a symposium about a woman in design. We had a day-long workshop at the Architekturzentrum.

By the end of the day, we realized, as Elana said, there were so many gaps in our knowledge, that this wasn’t going to assemble itself. We needed to come up with some kind of strategy, some kind of new way of writing a biography. That’s how we came up with the audacious, slightly crazy idea of 16 of us writing biography together. Sixteen people in four different countries researching and writing together to eventually be able to do what others hadn’t been able to do—I include myself—in 50 years. We managed to do it in two years, which was a long time, but at least we did it.

Laura: This is so impressive to me. It sounds overwhelming and scary trying to wrangle 16 people to work together, but also, in the last chapter where you talk about researching on Zoom together, it sounded very fun. I would love to hear a little bit more about the process of how you actually split up the work, manage to work together, and make it into a cohesive volume versus the normal edited volume.

Despina: Having an institutional partner was key. The Architekturzentrum Wien hosted the symposium but then also became a key institutional partner to develop the book. They created a virtual archive for us to deposit our discoveries as we were finding things to share with each other.

This is a different way from how most historians work. You usually are working as a lone scholar. That clearly didn’t work for someone like Ella Briggs. We had to share our materials because what she did in New York in 1910 directly affected what she did in Vienna in 1911, and so forth. We really needed to be working out this timeline and influences together. They dedicated staff to that. Then, once we actually started to find things, this virtual archive became a real archive that has now grown into a substantial collection.

Our research focused on our localities. That’s why we needed people in four different countries. Then in addition, we had a writing coach, which I think was really key to help us to figure out how to assemble this incredibly complex biography in a way that felt like a genuine life that wasn’t segmented, but where ideas flowed across geography and time. You can see Ella developing. That required a lot of conversations and figuring. It’s like a life—a life doesn’t happen in these compartmentalized chapters.

Elana: We decided to divide it between Vienna, which is a substantial part of the book, and the networks that were formed in Vienna. New York and United States with Despina. Then we asked for a colleague I worked with in the past, Celina Kress, to research Berlin because she had done plenty of work there in the past. Despina asked Barbara Penner to work in London. Then what happened was we had a certain amount of archival work, especially for Despina’s research as a graduate student. We did have a lot of colleagues here, like Katrin Stingl from the Architekturzentrum and Sabine Plakolm-Forsthuber, who worked a lot on Ella Briggs in the past.

But we needed something more, a really hardcore archaeological work. We found some in the Berlin archives, especially an amazing source was the restitution claims she made. Everybody said, “She didn’t build an archive. Schütte-Lihotzky had an archive. Ella Briggs did not have an archive. What’s going on? We will know nothing about her.” Then we located this restitution of hers. We see that she documented everything she did in Berlin.

Despina: Yes, these were the post-war claim that she made.

Elana: This was an amazing source of information. Then, also, for me, the biography, suddenly, I find a small note about a Parisian visit. Then Despina says, “We must include it. We must go after this source.” Then we entered the Parisian archives. Then I found a colleague in Breslau, now Wrocław, in Poland, originally in Germany. She was part of the detective group. She became suddenly obsessed with it. Then we figured out some amazing stories of Briggs in Breslau and her work for the Pringsheim there. It was fascinating.

Then I speak with a colleague at the MAK, who says, “Well, we have nothing about Ella Briggs.” I said, “Look, look, look again, look again at the archives.” Then the archivist said, “Well, I did find several letters.” I said, “Okay, let’s look at the letters.” It was really a building up, talking with each other, exchanging information. It was fantastic detective work we had.

Despina: The model that we used, we refer to it half-jokingly in the book, we refer to ourselves as the Ella Briggs Detective Brigade. The model that we worked with was this idea of a detective collaborative spanning international borders and trying to figure out, “Well, how?” We would have our virtual study rooms where we would meet. In some cases, we were discovering things together in those rooms. Having that capacity [to meet on Zoom] was also incredibly important post-pandemic to use this tool in a way that allowed for this international detective work to go along. As we were doing it, I was thinking this would be such a fantastic model to encourage others out there to become these detective collaboratives to see what’s happening in their neighborhoods or their cities.

I do think that the model of the lone historian is a straitjacket for complex histories. For Ella Briggs, Ella Briggs wasn’t just traveling like a tourist with a sketchbook. She was the architect of migration. Many women architects did have to migrate to find work, but there was more going on there with her. She was so curious. She was a traveler. She loved to encounter different ideas and different people and then blend them into something new. To understand those different contexts would have been extremely hard for a single historian, which is why this history didn’t get written for 50 years. It took someone who is an expert in all of these different locations, knowing what the politics were, what were the cultural discourses, who are these people that she’s meeting, to piece it together to understand what she was picking up in all of these different areas. That’s just not how traditionally historians have worked.

Laura: At the point of the time of the symposium, how much were you aware of, of her life? It sounds like you discovered so much, but at that point, did you just have a few different notes at different points in time?

Despina: Yes, we were really at the very beginning. The people who were at the symposium had all done research on her but had generally stayed within their national boundaries. We had pieces of the puzzle. We didn’t have the complete picture. By the day’s end, we had a sense that we could get there. We didn’t know how. In writing the book, we were also figuring it out in real time. It’s not like we sat down beforehand and figured out this is how we’re going to proceed.

It was really trial and error. We all shared in this obsession about finding out about her. I think that really helped because there were constantly little clues that you had to follow to get to the big discoveries and be able to piece things together. People did spend an inordinate amount of time in archives, in libraries, on ancestry.com, on all of these different sources to collect the pieces and then work together to bring them into a narrative.

Elana: In the first workshop that we organized, we had several women who did work on Ella Briggs. Katrin Stingl wrote a master’s. Sabine Plakolm was working also on women who attended courses at the Technical University in Vienna.

What was helpful for me in this process, in developing it, is actually to pursue the networks of Ella Briggs. In the chapter on her work as a designer, as she started launching her career as a designer, she actually united with feminists in Vienna. Yella Hertzka was the head of the New Women’s Club in Vienna. She had this powerful ability to move from informal institutionalization to an institutionalization. Through this, [Hertzka] also had the framework to allow Briggs to develop once she couldn’t find any clients as an independent designer. She gave her the background.

The networks also somehow, in this development of collecting information and how important they were, you could see how Ella Briggs grew up or matured or became Ella Briggs. She started as just one more bourgeoisie, Jewish background in the school, in the art school for women and girls. She was one of many. She became the woman who designed a major social housing in Vienna. This moved from 1898 as a 17-year-old young woman to 1925, 40-plus. She’s now 45, designing a major building in Red Vienna and a huge investment of money, which meant that they trusted her for it. She developed. The networks and her contacts and her social contacts, and how she maneuvered with these people, you could see how she developed to being Ella Briggs. A lot of it is also a media function, what happened in the Viennese media. She’s the first interior designer. This is already one major credit. Then suddenly, there were also women journalists who wanted to promote her. Then suddenly, one of them identified her not anymore as a designer, but rather as an architect. You have the architect woman coming even before she studied architecture. Parallel to it, these were at First World War I, and men are outside, not in the city, they’re fighting. She gets the jobs as an assistant in an architecture office. She’s just an assistant, but she wants much more. By the end of the First World War I, when women recognize that they have the ability and the power and intellect, et cetera, et cetera, they go for their dreams. This is where she went. She went to study architecture and became an architect. Then Despina knows about this relationship, New York, where she built her first houses before she came back to Vienna and participated in this project of the Red Vienna. In this way, you said, “Okay, there are the networks, but she knows how to maneuver them and how to achieve what she wants.”

Despina: These networks, sometimes they look like traditional architects, we can even say old boys’ networks, but many times they do not. What Elana is referring to is that Ella Briggs manages to build a very successful career on the basis of harnessing new networks, of being very creative in finding support and publicity through using not just traditional architects’ networks, but also women’s networks and friendships. Some of those friendships, we were able to trace them. They last for decades. They’re clearly very important in her life and in her work. In terms of the methodological challenges of the book, this was part of it too, that women architects’ careers don’t often look like those of men. You have to understand how they build their careers differently.

Laura: As you were doing the research, were there any discoveries that changed your whole opinion of her or her career, surprised you?

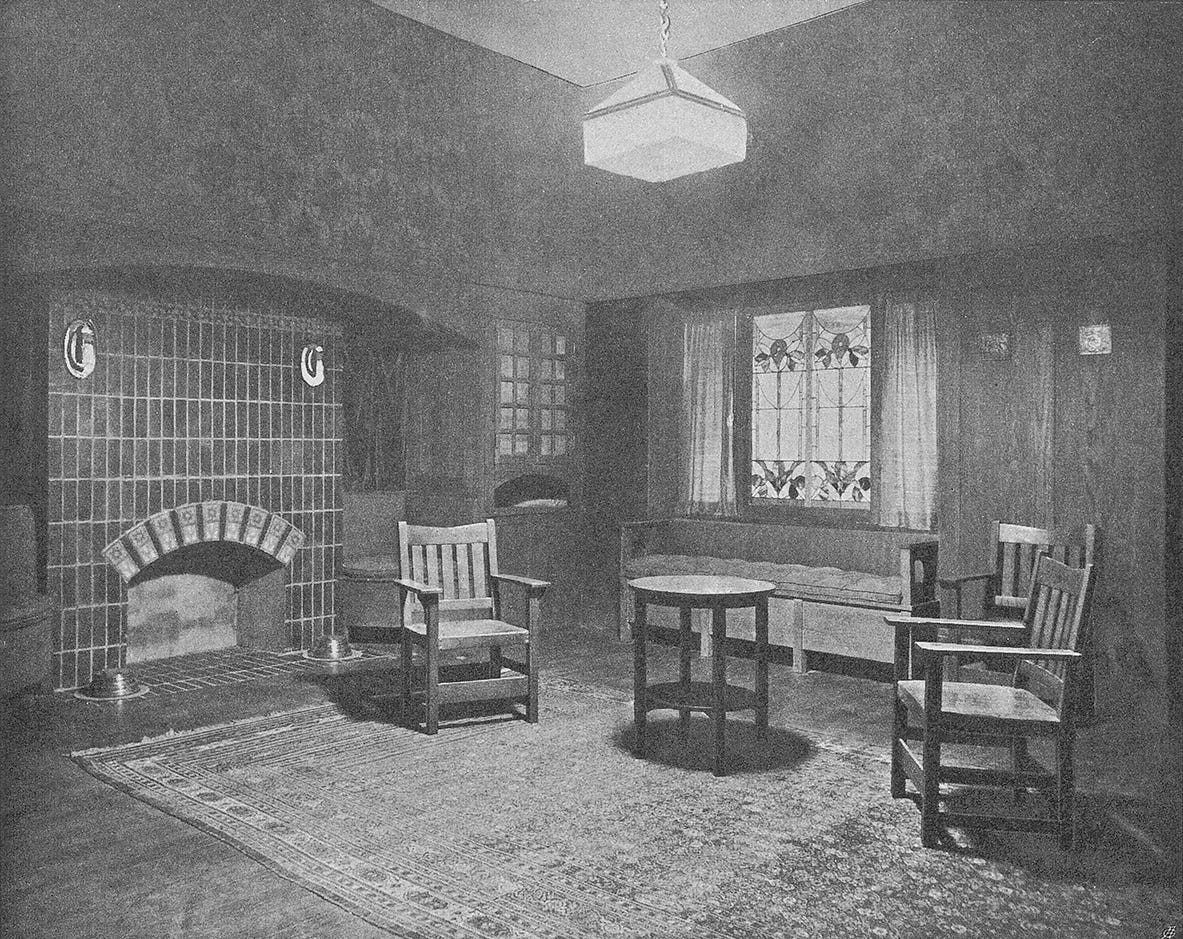

Despina: I think there were discoveries for each of our contributors. For me, the scale of her work early on in New York. We believe she was the first Secessionist-trained artist to work in New York. In 1908, she was central to the design of the New German Theatre, which was this massive German-language theater that attracted a lot of attention. It was a Secessionist space that has been forgotten. We discovered other large-scale projects that she did in New York at that time, including the New York Press Club. It was shocking how many projects we discovered that were new. The scale, the impact that she was having at the time. That New German Theatre was considered revolutionary. Critics were writing about it as, “This is an opportunity for New York and American designers to see a complete Austrian modern ensemble.” She had a very high profile. That was also, I think, shocking to discover, just how prominent she had been.

Elana: For me, it was this correspondence at the Museum of Applied Arts Vienna, where she suggests to open a design store in New York. This was a fantastic idea. A decade earlier, much longer even, than the Wiener Werkstätte opened their design shop in 1922. This meant that she looked all the time outside the box. The box was, “I am a woman artist, going to get married, and somehow continue with my hobby.” She didn’t accept it. She went to New York to get married. She separated eventually, and she continued an independent career: “I’m happy to be a designer, but I’m also willing to try and write a book about Renaissance buildings in Sicilia. I’m willing to start a design shop and try to facilitate this cultural transfer beyond my own design, allow American architects to see what’s going on in Austria at this time.” It was a very detailed correspondence, what firms she would like to address and what they would recommend her to address. She was really able to conceive a plan that was later picked up by the Wiener Werkstätte and the Austrian Werkbund. In 1911, she’s 31 years old, and her relationship is breaking apart, but still she wants to make sure she is continuing her career in New York. She’s doing it.

Then later on, what was for me fantastic was her writing. I’m very much into social design, and social design was never considered modern, as part of the modern project. Now, more and more, it’s integral part of the modern project. She set a model as a woman designer saying, “I’m more interested in the needs of my clients. The clients come first.”

Despina: She’s self-consciously a conduit for modernist ideas across borders. She is ahead of her time, not only with this idea of the Viennese design shop she wants to open in Manhattan, but in many other ways. As Elana mentioned, the user-focused design, decades before others will focus on that. The idea of curating style as a curation of trends and personal influences going against the idea of modernism as a hegemonic style. She doesn’t care if a roof is flat or angled. She thinks about modernism much more about how you live your life. Because she centers the client, that translates into a very personal vision of modernism. Again, decades before that really becomes more popular.

In terms of really some of the shocking discoveries, Celina Kress is our Berlin colleague. Her discovery—and Elana was involved in this too—of the post-war restitution claims that Ella Briggs filed are an archive. In her insistence on justice after the war, she ended up documenting her career in a way that was astonishing. It was those claims allowed us to reconstruct a lot of her career. These things are out there, and we know that there will be more discoveries. We know there are many more houses, for example, in the United States, but we also know they’re elsewhere in Europe. Finding them does take this kind of innovative detective work.

Elana: One of the reasons that she disappeared from the chronicle of Vienna and modern architecture was that her career was interrupted several times. Sometimes she initiated moving from Vienna to Berlin, to New York, but at the end of the process, 1935, she’s forced to leave Berlin, and she moves to London. Then you have one chapter in Finding Ella Briggs about comparing Schütte-Lihotzky reception in Vienna and Ella Briggs, and the extent they were never considered as part of the Austrian scene for many years. It took a while—the whole scholarship from 1990s and 2000—to regard them as integral part of the modernist because they left and they had a better time somewhere else. This was, of course, a false assumption. They struggled tremendously in the new location. That’s why the restitution files that we found was so critical because we had her voice there.

Then there was another files we found that were even more interesting in Berlin. It was in the city archives, where she applies for a German citizenship. There she has to prove that she’s German. She comes from a Jewish background, she left the Jewish religion, she converted, although she relied mainly on Jewish networks in Vienna and Berlin. These were her colleagues, but she comes back, she stays with Jewish friends, all through the way. When she’s in London, she corresponds with Jewish exiles. She left it. Then 1932, she has to claim that she is a German, and she starts detailing what in her that’s German, what in her could apply. She refers to the fact that her brother was the director of the New German Theatre in New York, that another member of the family was a major da da da. This was her voice, and for me, it was fantastic because it showed that she’s a fighter, like Despina noted now. She’s a real fighter. She’s insisting on her way. It’s also in the correspondence, you could see how she loses the patience, “Didn’t you understand what I wrote to you in my letter?” She was not an easy woman. She was not that nice of a woman. She was rather an ambitious achiever, and that’s why it’s such a tragedy that nobody recognized for decades how much she achieved by herself.

Despina: Ella Briggs is this figure who keeps popping up at all of these central moments of history, like the Secession in Vienna, Gilded Age in New York, Fascist Italy, the rise of the Nazis in Germany, and socialist Red Vienna. All of these moments are incredibly complex to understand, for example, what it means in 1932 for a woman from a Jewish background to be arguing that she’s German. Again, it’d be hard for a lone historian to figure this all out.

Laura: She was obviously a great writer, a good writer. It was too bad that she never wrote some form of a memoir because she really did live through so many interesting points of time, and as mostly a single woman, Jewish woman alone, in difficult circumstances. She wasn’t easily moving through these points in history. Why do you feel that her story is so important to tell?

Elana: For me, it was important because of my research on other women designers and the emigre networks and how they function. There were two elements that I thought that would make a change. First was the fact that she made history in Vienna through the social housing. Second is that she managed to operate networks beyond borders in a time where you wouldn’t have expected it from women to do. To manage to jump over to New York and get some assignments for architecture. Her personality is critical. Her personality is critical for the story.

Also, in regards to questioning the canon, what are we expecting from the canon? You spoke about her memoirs. She has one letter to Phyllis Morrison from just before she died, where she reflects on her life. She says there are many losses, and she still wants to give Phyllis Morrison, her great niece, something to remember. It’s not the memoirs, but her voice that I think that was so important for me to see through her articles. She really wanted people to live better. She had this mission: What would make a couple feel better when they enter a new house? How would design improve their lives? This, you will not find with Gropius or with Mies van der Rohe, or with Hoffman. It’s more a kind of tradition of maybe of Adolf Loos in a way, but from a strong woman’s voice.

You have her changing the chronicles of Viennese Modernism, and you have her also achieving across borders many projects that usually women did not at the time. Then you have her ultimate voice showing you a way how to live better or how to improve your standards of living.

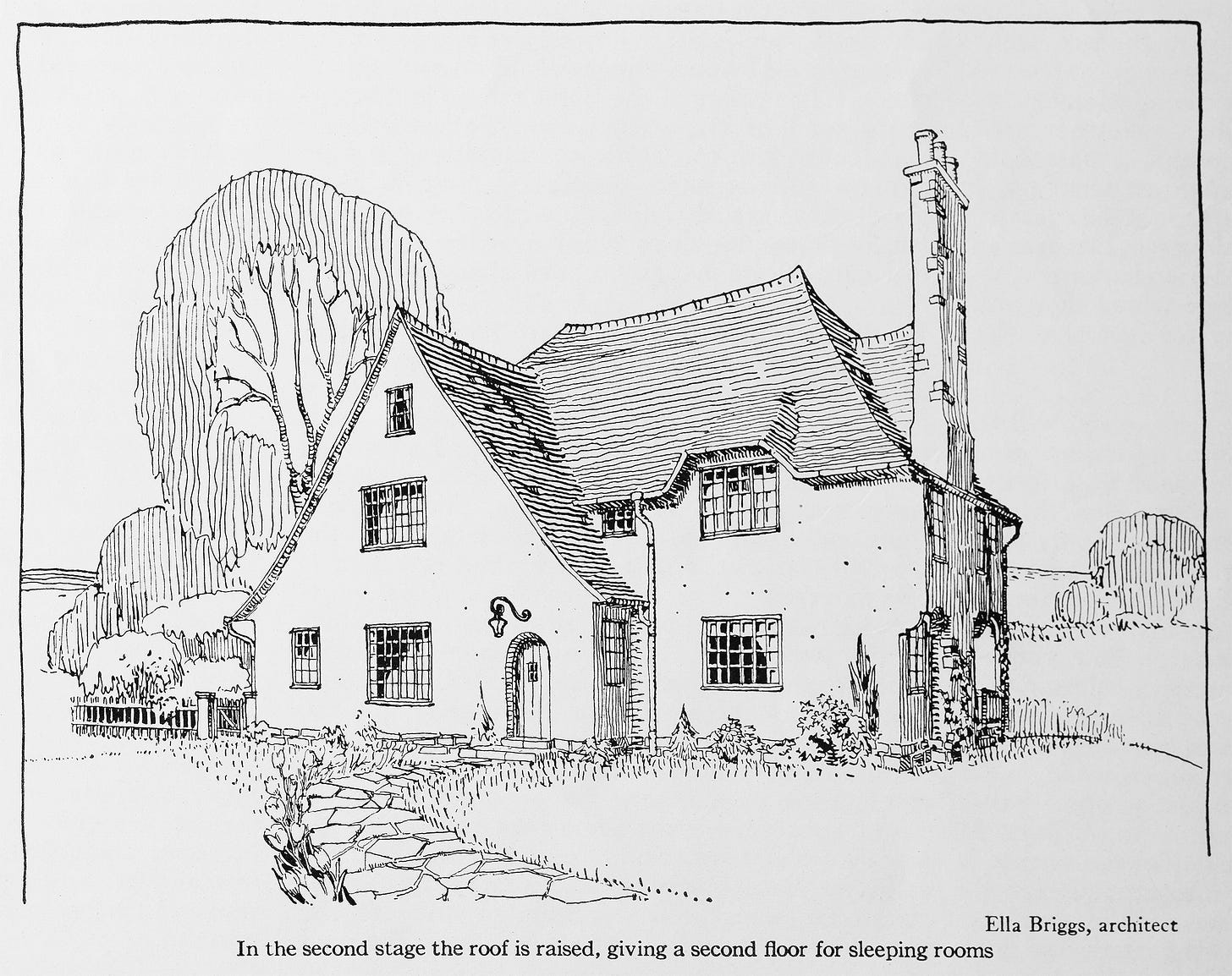

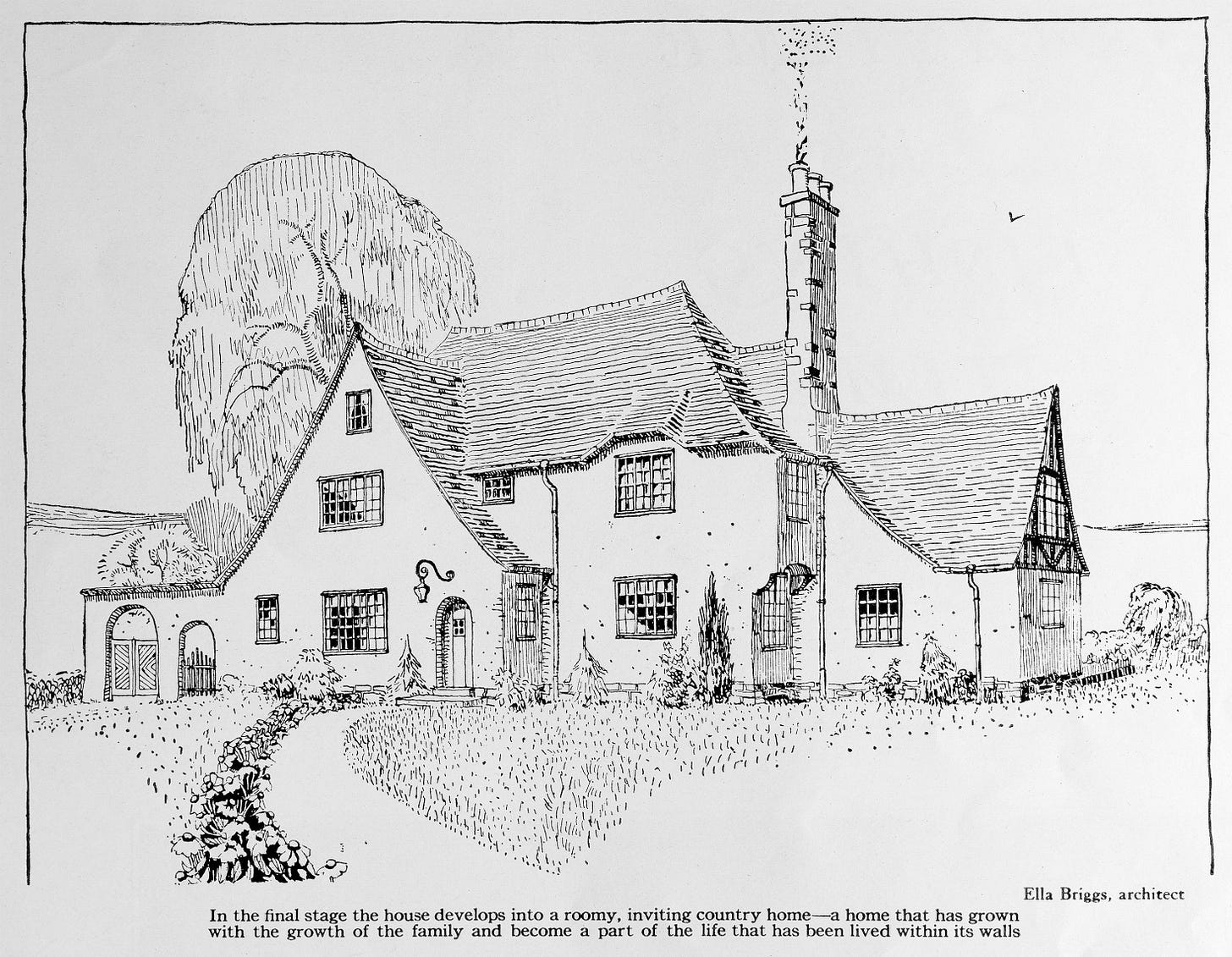

Despina: For example, her idea of the house that grows is, again, something that was radically progressive, but still incredibly relevant and pressing in terms of life cycles of architecture and how we can stay in place if we want to. From being a young person to developing your life, perhaps marrying, perhaps having children, and then aging in place. She was already anticipating that in the early 1920s.

I agree with Elana that, looking at Briggs, why her story matters is that it changes our ideas of how modernism developed, the flow of ideas, the complexities of the story of modernism that ultimately challenges the canon. Also makes the story of modernism so much more interesting. She is an inspiring figure. I think we were all absolutely obsessed and fascinated by her, but also very much inspired by someone who faced so many hurdles and sometimes life-threatening dangers and persevered. This is a story of incredible perseverance.

For me, too, the importance of this is also in how we wrote this story and the idea that we refused to accept the idea that this history was lost to us. I think by shifting how we work, there are so many other histories out there that can be recovered and that matter to people. This is also a story about methodology.

Laura: Are there other women that you are interested in trying this collaborative approach with?

Despina: A topic right now of women architects’ immigration is very timely in that, as I mentioned, women in design often did have to move for job opportunities. Finding a method that captures these lives and careers across boundaries is incredibly important. That’s been done also for men. With women, again, because the way that they construct their careers are not necessarily the way that the canonical figures in modernism did, we need different approaches to capture their stories across migration.

Now that we’ve built this archive at the Architecture Center, I do hope that there will also be more work done. The obsession with her is not over. I do hope that people continue to look into her life. Elana mentioned her husband, Walter Briggs, who I’m obsessed with him too. I’d love someone to dig into his life. I think there are a lot of things that we’ve left very happily incomplete, hoping that people will take up the challenge of bringing Briggs’s story further.

I don’t know that I really want to go back to a traditional way of working because this was really finding things together, figuring out things, working together. It’s just a much more robust, and I think creative, and enjoyable process.

Elana: The collective work that we worked on Ella Briggs, we would like now to collaborate with the Architecture Museum in Wrocław in Poland. They would be interested in a cooperation and also working there on Ella Briggs because she did design there, and she designed for a very prominent Jewish family, the Peringsheim.

We figured out that what we tell you now is different when you tell it to American audience. It’s different when you tell it to Viennese audience, or you tell it to Polish audience, or in Poland, or in England, or in other countries. Each one of them referred to Ella Briggs in a different way, not only because of what she achieved in different countries, but regarding her travelings as a woman. In this regard, we do want to tell her story. I would be curious how people would react to her. What we hope is when we present it in London, or we present it in Vienna, that women will come up. It happened to me in Brno in Czech Republic a year ago, “Oh, I’m working on this woman. How can we work together, or how should I reconstruct the story?” Then we have this model, this Ella Briggs book. We say, “Look at the Ella Briggs and see how we trace her career.” The model is Ella Briggs. Despina and I, I think, we managed to somehow conceive a whole story and the skeleton that anyone who follows the book could try to not imitate, but try to follow in a way, or to rework in relation to their own chosen subject.

Despina: Very much like Ella Briggs did with her architecture. I think this point that Elana is raising is really important, the translation into new, different cultural contexts. We encountered this with our own project, but the institutions, the funding, the opportunities available in each place are going to be different. Working with this model, but adapting it to new contexts, I think, is really important to mention.

Another thing that Elana mentioned that’s very important is that we looked back to the collective efforts of feminist scholars, architects, and artists in the 1970s when women first came together to try to discover their own histories. There was this moment in the ‘70s and the ‘80s, up until the early ‘90s, of incredible collaborations, sometimes with museums, sometimes independently, but working together that produced these very important breakthroughs in our understanding of women’s design histories. Right now, we are in this moment. It’s not just our project. There are many projects out there that are collaborative efforts, collective efforts. What I want to do is work to encourage that new wave of collective feminist work because it does require different kinds of institutional support from the model of the lone scholar.

That was one of our challenges, too. We were very lucky to find our institutional partners and to find a publisher, but working in this way is expensive. The grant-making institutions, in the humanities, typically don’t look for projects that are being written by teams. To keep going with this very important moment that we’re in of collective history writing around women or other marginalized histories, it is going to require pushing our institutions to support that work.

Laura: You have this online archive that you’ve created that anyone can view, which is amazing.

Despina: This project has been a challenge in a good way, not just for us as writers of a biography, but it has also provoked lots of great questions for the Architekturzentrum Wien in terms of, how do you create an archive in the absence of one? Many women architects, their material has either been dispersed or disappeared, especially if they were women who were working in migration, so this is also a migration story question.

Now, as that archive has started to grow, but how would you put this on display? How do you visualize her work in interesting ways when you don’t have the traditional collection that you might have for someone else, or, as Elana is also saying, the story might be told differently. This is another really interesting institutional question. This is where, too, because of this moment we’re in of collaboration to recover the histories of women in architecture, there have been a number of exhibitions on women in architecture in the last just a few years. They’ve been grappling with this idea, too, of what does a museum show look like when you’re talking about figures that have been marginalized but are not in the canon? I think that can lead to really important discoveries as well.

There is a real hunger for these stories. Especially from when I encountered younger colleagues who’ve heard about this book. They want to know, “How did you do it?” Elana mentioned this too. “How did you manage to do this?” I would say that this is now a question for also curators and archivists. It’s like, “Now, how do you take up these stories and make them come alive?”

Laura: It definitely had me thinking, “Oh, who could I collaborate with and who do I want to study?” Reading this book made me want to do a similar project because I’ve never worked on anything in that manner. Research and the detective work is really fun, and to do it collaboratively across countries would allow you to find things that you’d never find by yourself. It was very inspiring to me in that way.

Elana: What happens with the woman that traveled a lot and migrated by her own wish and was forced to? Someone asked me, so how would you define her? I personally would define her as an Austrian-British, but I think why can’t she stand on her own? You find her in New York, you find her in Austria, you find her in Berlin, you find her in London, then in Boston. People are afraid from her. Maybe the physicality of an exhibition would give a way that people could interact with her physically that would not be so scary. She was bigger than life itself, in a way, through her geographical state and stations and embryography.

I think, for me, it’s first that Austria would recognize her beyond the men who wanted her to be part of the Red Vienna Club. I think it would be good to have her name being somehow rooted better in Austria, and then we would move on to other places.

Despina: This is a fascinating point. There are so many things to unpack, but the way that histories are cultural, but they’re also national. Who does Briggs belong to? Like Elana is saying, it’s really important that she be recognized within the history of Austrian modernism and in Austria. There’re a different set of politics going on there from trying to also present her as an international figure. Ultimately, this all goes down to who is recognized, who does show up in the histories, who does show up in the museums, and in the books. A lot to unpack, to continue unpacking.

Laura: Really fascinating. Congratulations on everything that you uncovered.