Recently I was flicking through one of the 1970s Mademoiselle magazines from my archive when I came across an editorial I somehow hadn’t noticed before. Photographed in the Richard Feigen Gallery on the Upper East Side in Manhattan—known then for radical, more cutting-edge works, it later came to focus on Old Masters—this editorial uses a show by pop artist Allen Jones as its backdrop.

Art galleries as the setting for fashion shoots was a common trope in fashion magazines—since at least the 1930s, fashion photographers had been placing models within museums and galleries. There the art acts not just as a form of background wallpaper but also cultivates the image of the model as a cultured society woman. As historian Änne Söll wrote in an essay on Cecil Beaton’s use of Jackson Pollock paintings as a backdrop for a series of fashion photos in Vogue in 1951, “The function of these “cultured” spaces is to convey the impression of an activity in keeping with the station of a worldly woman. Museums and galleries serve as semi-public spaces well suited for ladies of high society, spaces that are safe, cultivated, and cultivating. It is not about making fashion more noble through its association with art but primarily about an appropriate setting for the fashionable woman of the world.”

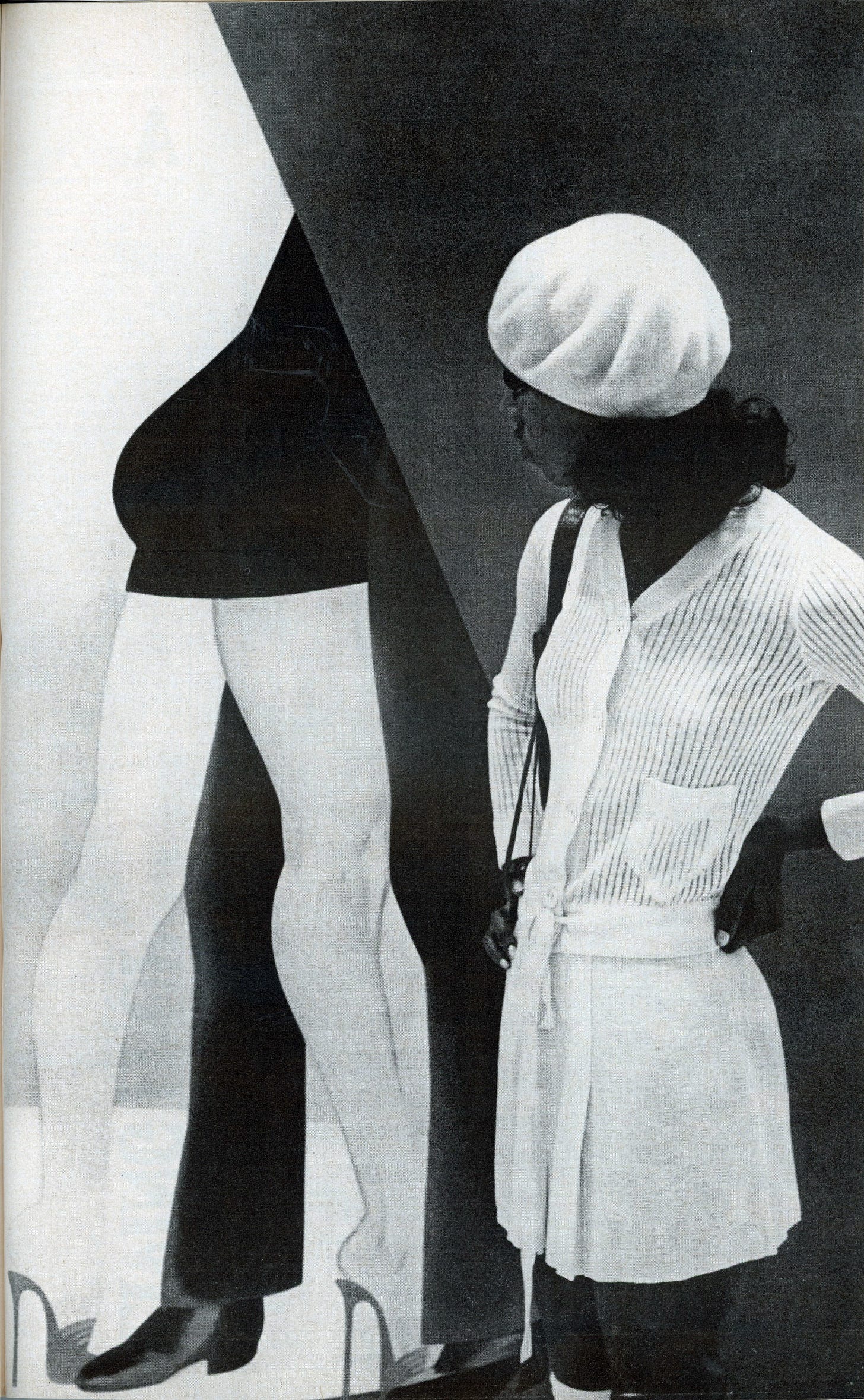

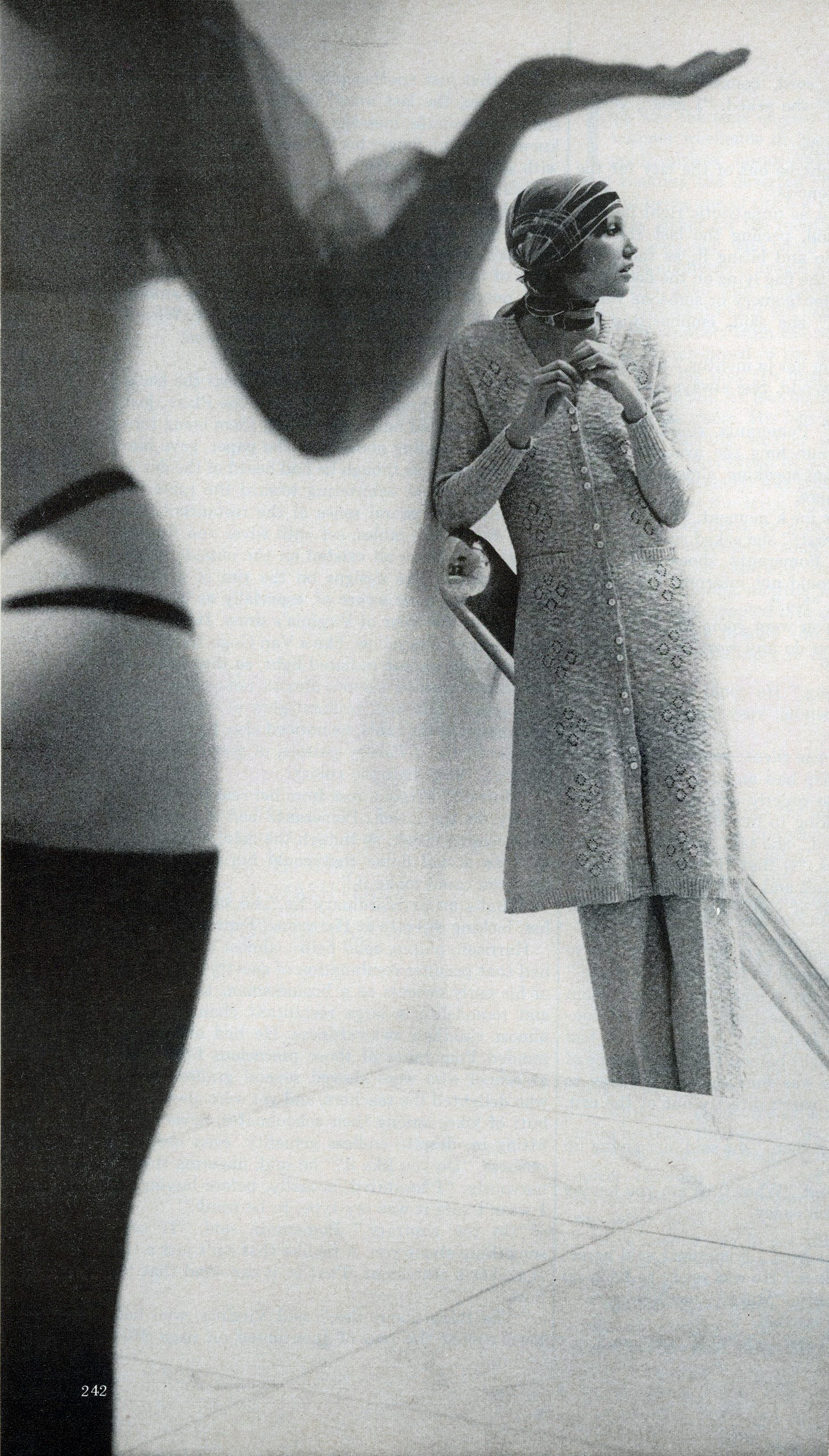

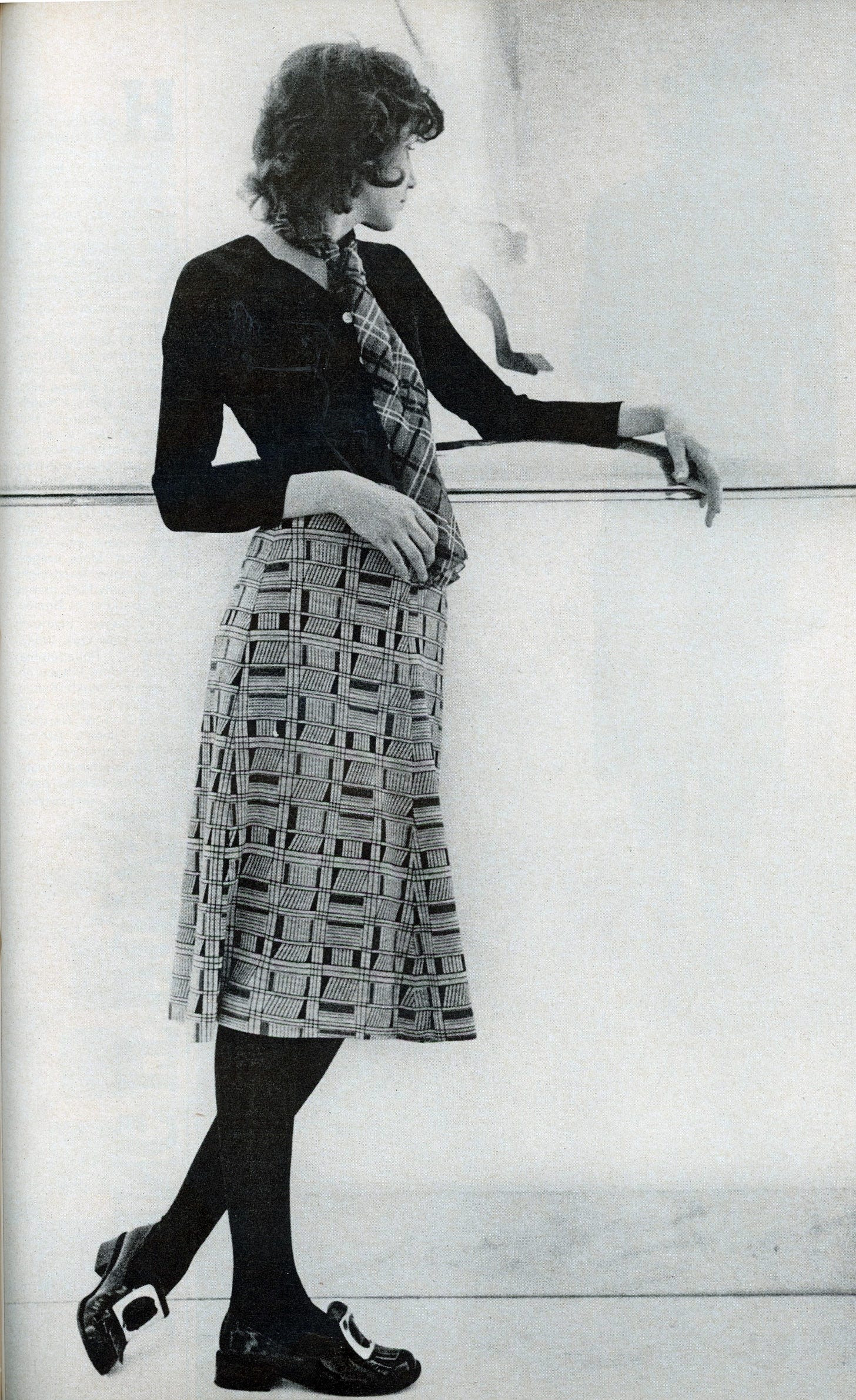

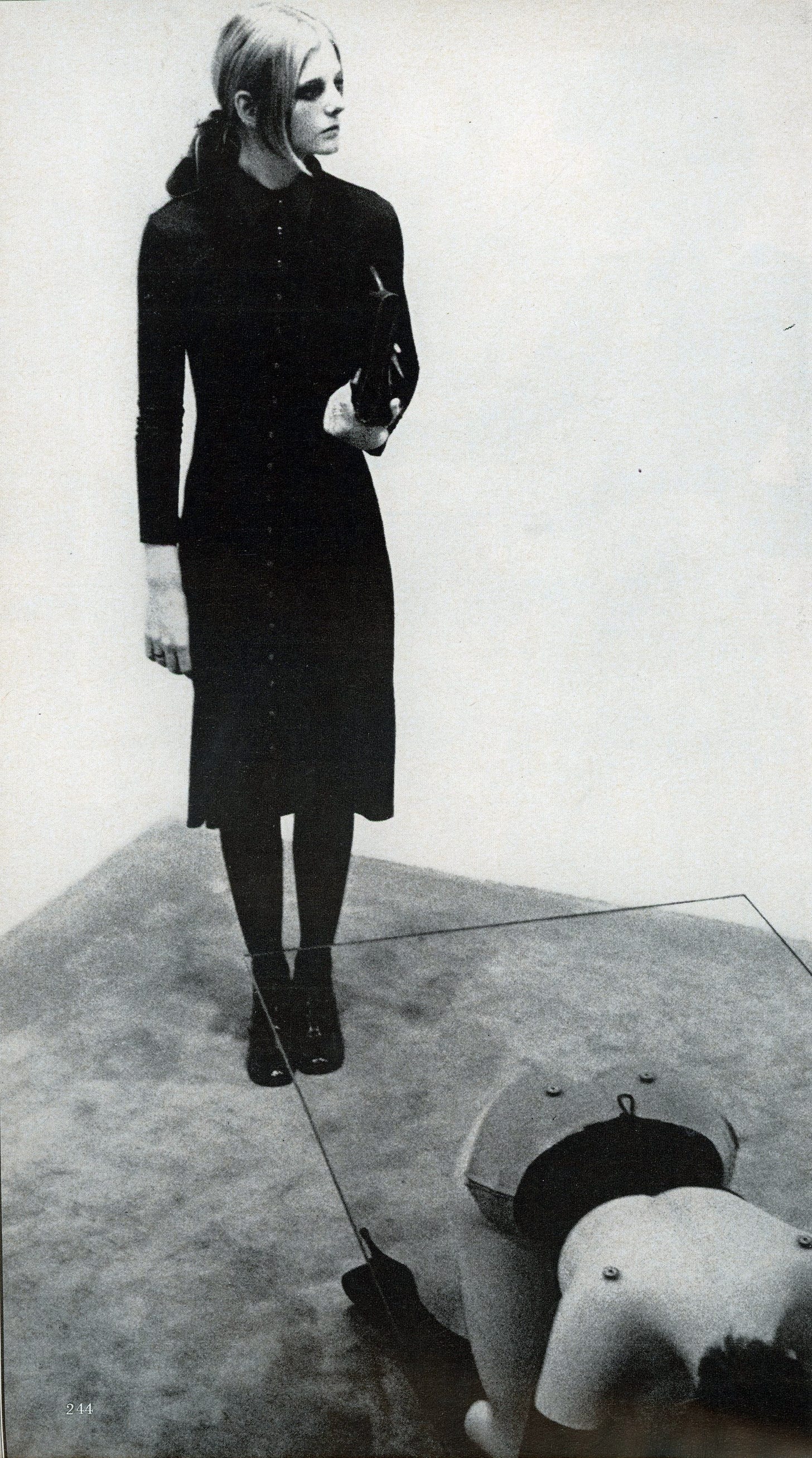

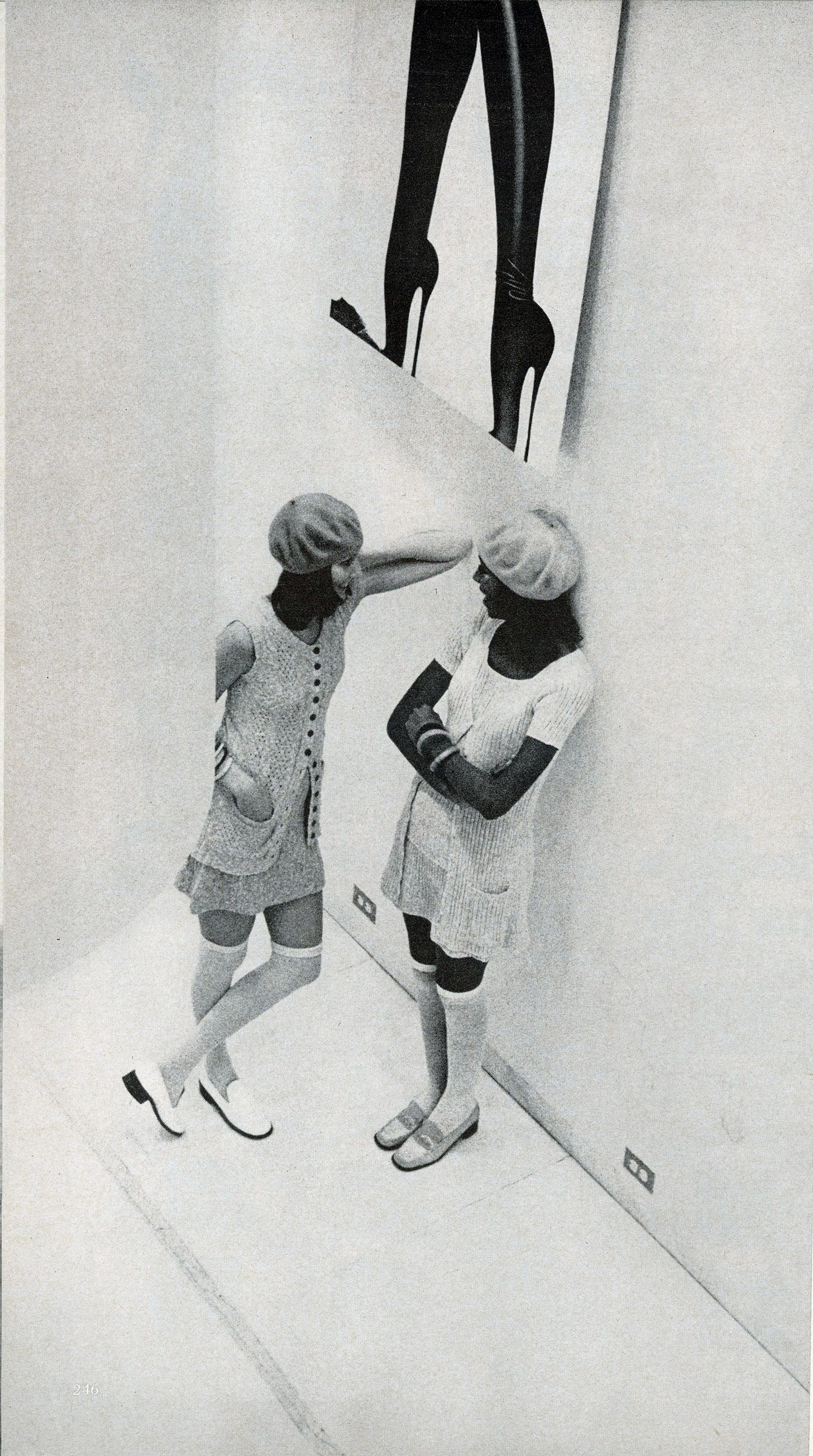

Unlike earlier editorials by photographers like Beaton or John Rawlings (such as the Mondrian’s and Brancusi’s seen in a January 1945 Vogue shoot), this photo story by André Carrara (for the most part) poses the models in a looser, more casual way. Instead of being statically positioned almost like sculptures in front of the art, Carrara’s mannequins appear more like normal gallerygoers candidly caught while moving through the stark white space. It’s as if two friends happened upon the gallery after brunch and ventured in without any knowledge of the work on display, happy to contemplate the art while continuing to gossip.

“…the photographer takes over the role of an artist: he “pictures” the model with his camera in a way that makes his photographic staging correspond with artworks, or, like Beaton, self-consciously compares his photographs with existing paintings. At the same time fashion is revaluated by art; the fashion photograph itself is raised to the level of an artwork.” - Antje Krause-Wahl

What’s interesting is how little focus is put on the provocative aspects of the art—Jones’ sculptures and paintings merely exist, taking up even less photo space than the aforementioned Pollock’s or Brancusi’s, yet this exhibition and these works were highly controversial. The centerpieces of this show were Jones’ now infamous “Table” and “Hatstand,” which for over fifty years have been the subject of many thousands of words debating their misogyny (as seen with this 2014 Guardian headline, “Is Allen Jones’s sculpture the most sexist art ever?”) The Artforum review of the Feigen Gallery show describes them as “monstrously dead effigies representing a highly specialized fantasy female—the svelte, cone-breasted, impersonal dominator of the male” that are “drearily banal.” While feminists and many critics attacked the fetish-inspired works, others responded positively to Allen Jones’ highly referential, playful expansion of pop art. Carrara and Mademoiselle waded into this drama by completely ignoring it; the text simply mentions “living it up at the shiny new Richard Feigen Gallery where post-Popist Allen Jones's ladies have been hanging out until recently.”

The art gallery here still acts as a cultured space used “to convey the impression of an activity in keeping with the station of a worldly woman”—that “worldly woman” is now also one who is undisturbed by latex and nudity, a thoroughly modern 70s girl clad in the new midi-length fashions.

“Jones’s paintings are not clinical examinations of a fetish for rubber or leather; rather, these highly tactile materials fulfill a valuable function in stressing the surface of the picture and in encouraging an immediate and physical response from the viewer. Neither are the paintings indicative of a lecherous taste for female legs, cleavage or the rather more specialized attachment to shoes with stiletto heels. This concentration on a select range of forms arises from their value as standardized symbols, as a means of gaining access to a universal idea through the more directly comprehended example from the material world. Jones’s work is sexually-derived, but its erotic substance lies not so much in specific images as in the contemplation of the mystery of sex and creation.” — Marco Livingstone

Last February I visited Allen Jones in Oxfordshire, where I interviewed him for my podcast, Sighs and Whispers. You can listen to our conversation on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Soundcloud.

“Living It Down,” Mademoiselle, April 1970. Photos by André Carrara.

Hems have stopped hawing. They've just about leveled off now (for day) at the thigh-high and the calfway mark. Here, turnouts that live it down living it up at the shiny new Richard Feigen Gallery where post-Popist Allen Jones's ladies have been hanging out until recently.

ALLEN JONES, R.A.

1969

STANDING FIGURE (HATSTAND)

ALLEN JONES, R.A.

1969

TABLE

ALLEN JONES, R.A.

1968

TWO TIMER

ALLEN JONES, R.A.

1968

WHAT DO YOU MEAN WHAT DO I MEAN?