Esther Williams: Swimming Superheroine

I wrote this piece on Esther Williams for Chandelier Creative five years ago—since the pandemic, they’ve redone their website and the essay section no longer exists online. As it is summer here in the northern hemisphere—and my social media feeds are full of everyone I know swimming in lakes, pools and oceans—it seemed the ideal time to re-share this piece on everyone’s favourite cinematic swimmer. Focused specifically on her water work, this piece doesn't delve into her non-aquatic movie roles.

Other than a few minor grammatical edits and new photos/videos/gifs, there have been no larger changes to this essay.

Esther Williams: Swimming Superheroine

Esther Williams has become so enshrined in pop culture that the mere mention of her name draws up visions of Hollywood aquatic fantasies. The first pro swimmer to dive from the pool into the movies, she created her own genre of films in which she was the sole star.

Swimming competitively from age 14 in Los Angeles, by 17 she had qualified for three berths on the 1940 U.S. Olympic team heading to Japan. Much to her dismay, the Olympics were canceled in 1939 due to WWII, ruining her dreams and leaving her stuck in a job as a stock girl at I. Magnin’s department store. Her photograph in a local paper caught the eye of theater impresario Billy Rose, who was keen to try her out to be Olympian Eleanor Holm’s replacement in his all-swimming, all-dancing, all-singing Aquacade at the Golden Gate International Exposition. Winning the lead of Aquabelle #1, Esther played opposite Johnny Weissmuller, an Olympian-turned-Hollywood star. With her all-American looks and perfect swim-toned body, it’s unsurprising that she quickly caught the attention of MGM, which put her under contract in 1941. MGM required her to have nine months of acting, singing, dancing, and diction lessons, on top of her daily swim training.“If it took nine months for a baby to be born,” she said of her preparation, “I figured my 'birth' from Esther Williams the swimmer to Esther Williams the movie actress would not be much different.” Starting in 1942 with smaller, love interest roles in non-swimming movies, by 1944 she took the lead in the first aquatic musical, Bathing Beauty. The water was Esther Williams’ mode of seduction, transforming her from a sunny, pretty yet wooden actress on land to a magnetic movie star when wet. With her first dive, Williams took control of the story arc and of the audience’s attention; her performance was so compelling that the studio renamed the film (originally titled Mr. Coed) following reactions at advance screenings.

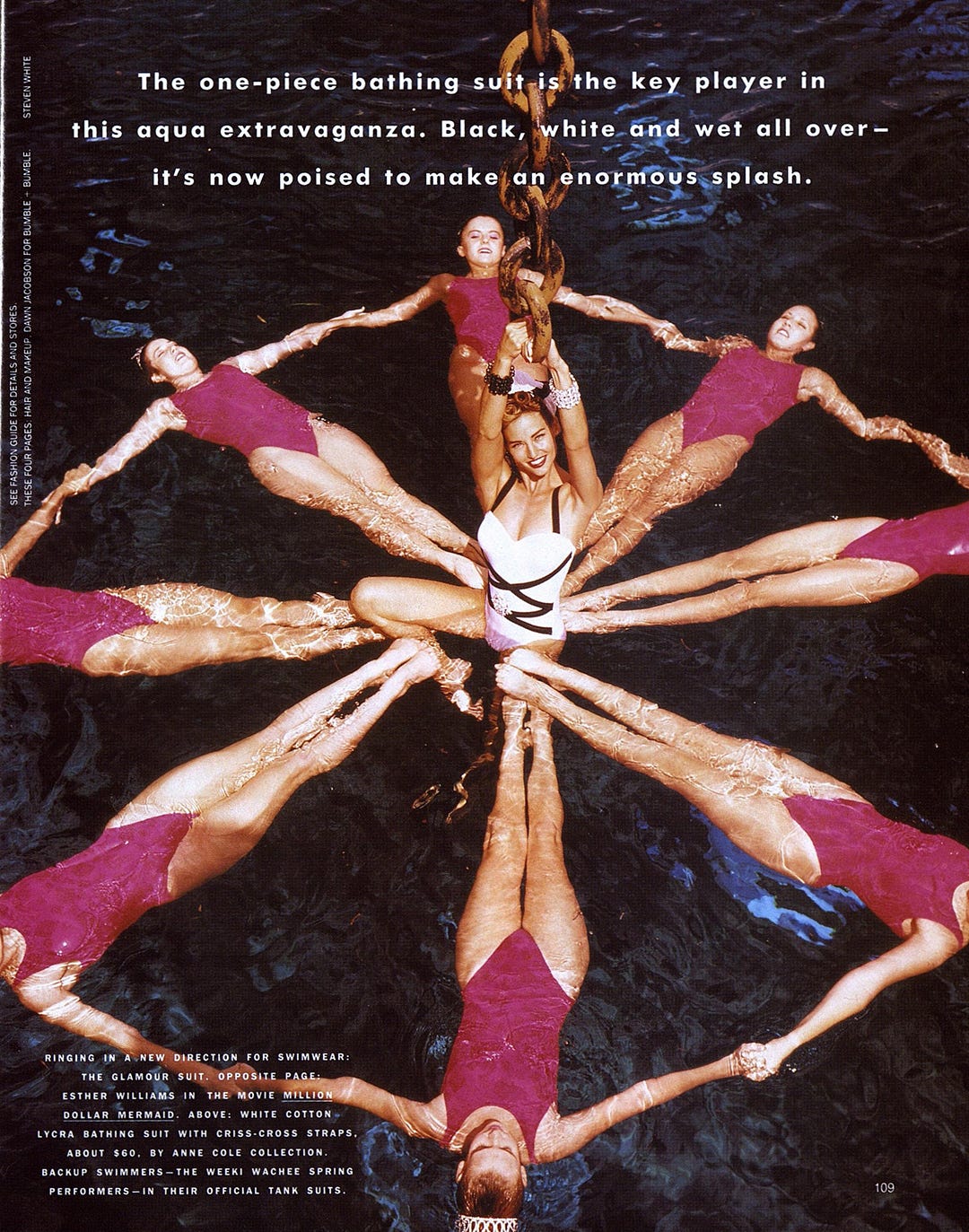

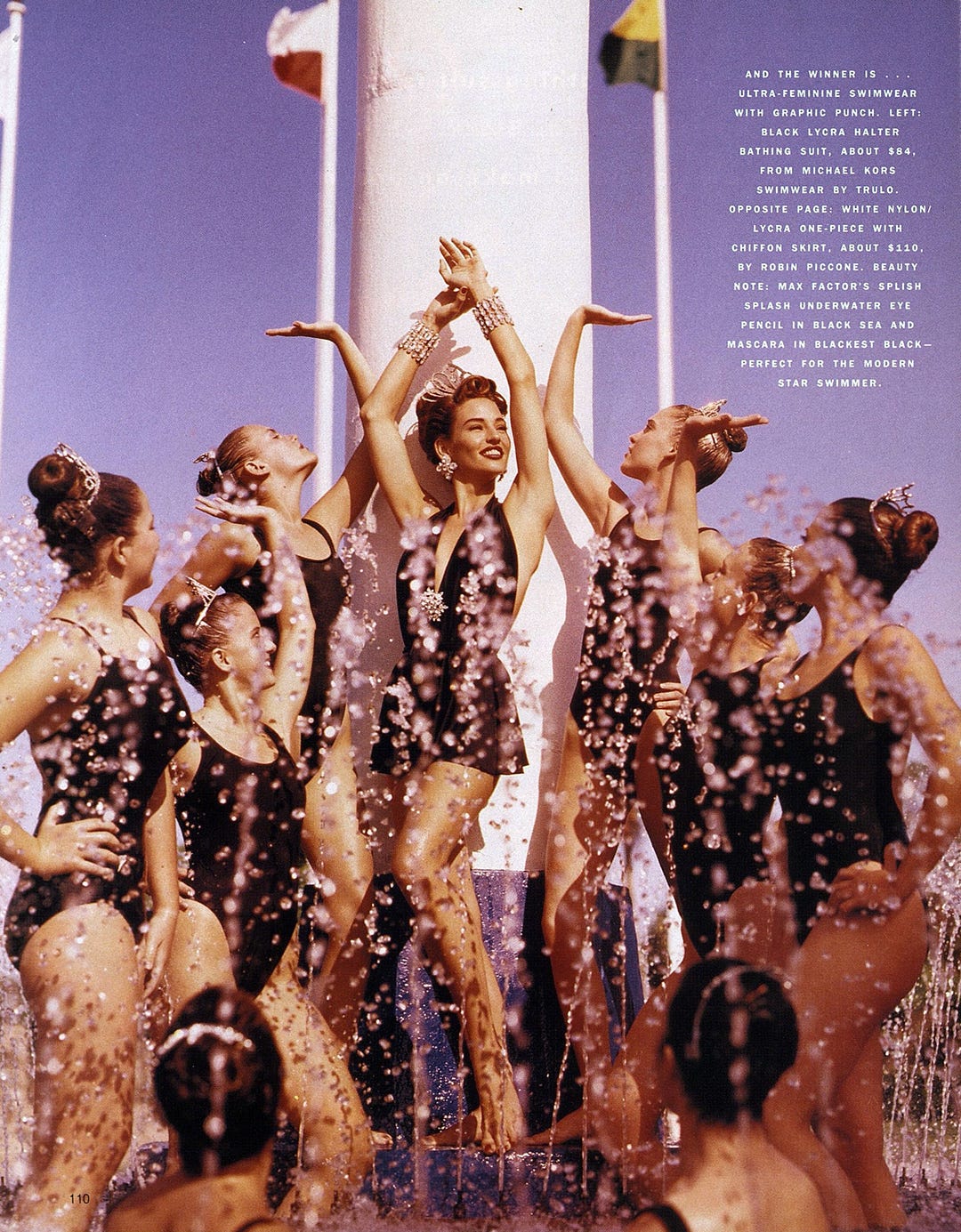

Drawing from both Billy Rose’s Aquacade and the Busby Berkeley movie musicals of the 1930s, the aqua-musicals Williams made in the next twelve years included elaborate water ballets with corps of swimmers creating synchronized, hypnotic patterns in the water on over-the-top sets. In these films, Esther Williams brought to the forefront of cinematic artistry the little-known sport of synchronized swimming. At Stage 30 on the MGM lot, a special 90-foot square, 20-foot deep glass-walled pool was built, complete with hydraulic lifts, hidden air hoses, and special camera cranes for overhead shots. Williams recalled of Bathing Beauty, “No one had ever done a swimming movie before, so we just made it up as we went along. I ad-libbed all my own underwater movements.” John Murray Anderson, an acclaimed Broadway director, choreographed Bathing Beauty’s water ballet. The 31 water nymphs practiced for 10 weeks. Over the years the productions became increasingly elaborate, with the plots often increasingly tenuous: film as a showplace for the prowess of athletic bodies in unity, all shown in gaudy Technicolor (“Technicolor brought to life the water, the spectacles and even my own movie persona in a way that simply didn’t work in black-and-white”). Busby Berkeley, the most-famous choreographer of musicals (both stage and screen), joined forces with Williams on two films, Million Dollar Mermaid (seen in the top gif) and Easy to Love, creating the apotheosis of the genre with her at the center as a Venus or Circe, enchanting the water through her movements. The “cinemermaid” was usually clad in swimsuits designed for both their ease of swimming and glamour, the sequins and lame fabric lending them a dramatic touch that was softened by the rather modest cuts of the suits. Unlike later bikini-clad movie babes, Esther’s body was revealed by silhouette and not by exposed skin.

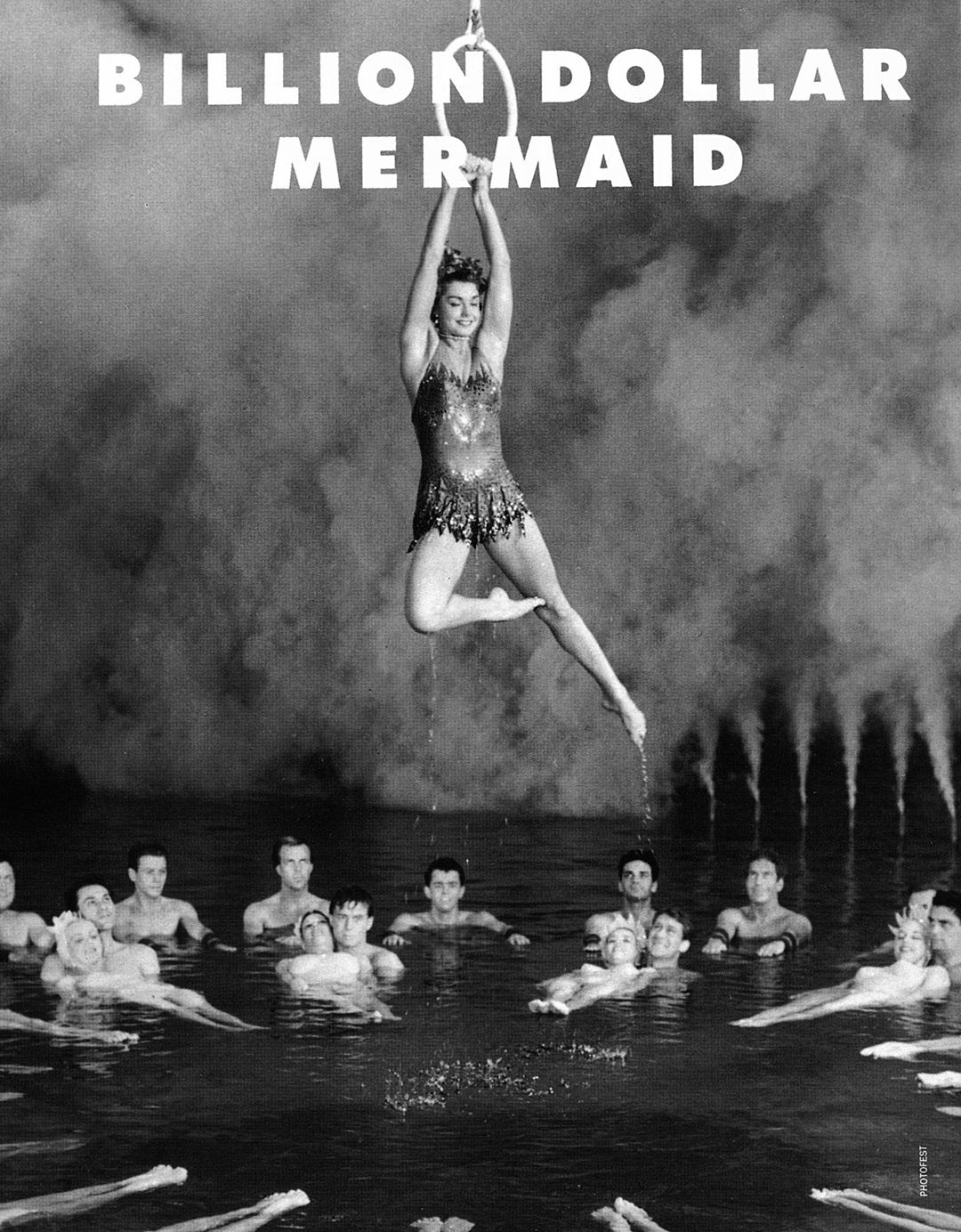

Synchronized swimming being a novel idea, the swimmers aiding Esther were often professional dancers with little-to-no water experience. Though they and Williams often suffered from water inhalation and other afflictions, what remains most memorable about these performances is their sunny smiles and grace while performing intricate and difficult routines: the all-American girl who retains a smile no matter how she suffers. A keen athlete, Esther performed all of her own stunts including a waterskiing spectacular while pregnant in 1953’s Easy to Love. She broke her neck while filming perhaps her most famous film, Million Dollar Mermaid (1952), a biopic of the famous Australian swimmer Annette Kellerman. In a routine designed by Berkeley, Williams did a swan dive off an 80-foot stage into the water while wearing a sequin swimsuit and heavy metal crown. This iconic water ballet—complete with colored smoke and fire—almost killed her. Rather understandably, Williams gradually retired from cinematic aquamusicals over the next few years.

Rather remarkably, the other swimmers who went to Hollywood did not star in water-centric films. Eleanor Holm usually played herself, while Williams’ Aquacade partner, Weissmuller, became best known for playing Tarzan in eleven films. His swimmer’s physique was exploited on screen, but he rarely swam on camera. Other athletes made the same transition from the field to the movies, yet none achieved the same long-lasting fame as Williams. Sonja Henie was a Norwegian figure skater and three-time Olympic champion who signed with Twentieth Century Fox in 1936. The skater’s box office success led Louis B. Mayer on a hunt for a sports star of MGM’s own. Intriguingly, while skating was incorporated into all of Sonja’s films, none of them had the same over-the-top productions that Williams became known for—instead they functioned as beautiful interludes and plot devices. In the realm of sports-on-film, Esther Williams’ movies stand apart for their sheer inventiveness and large-scale, multi-layered productions.

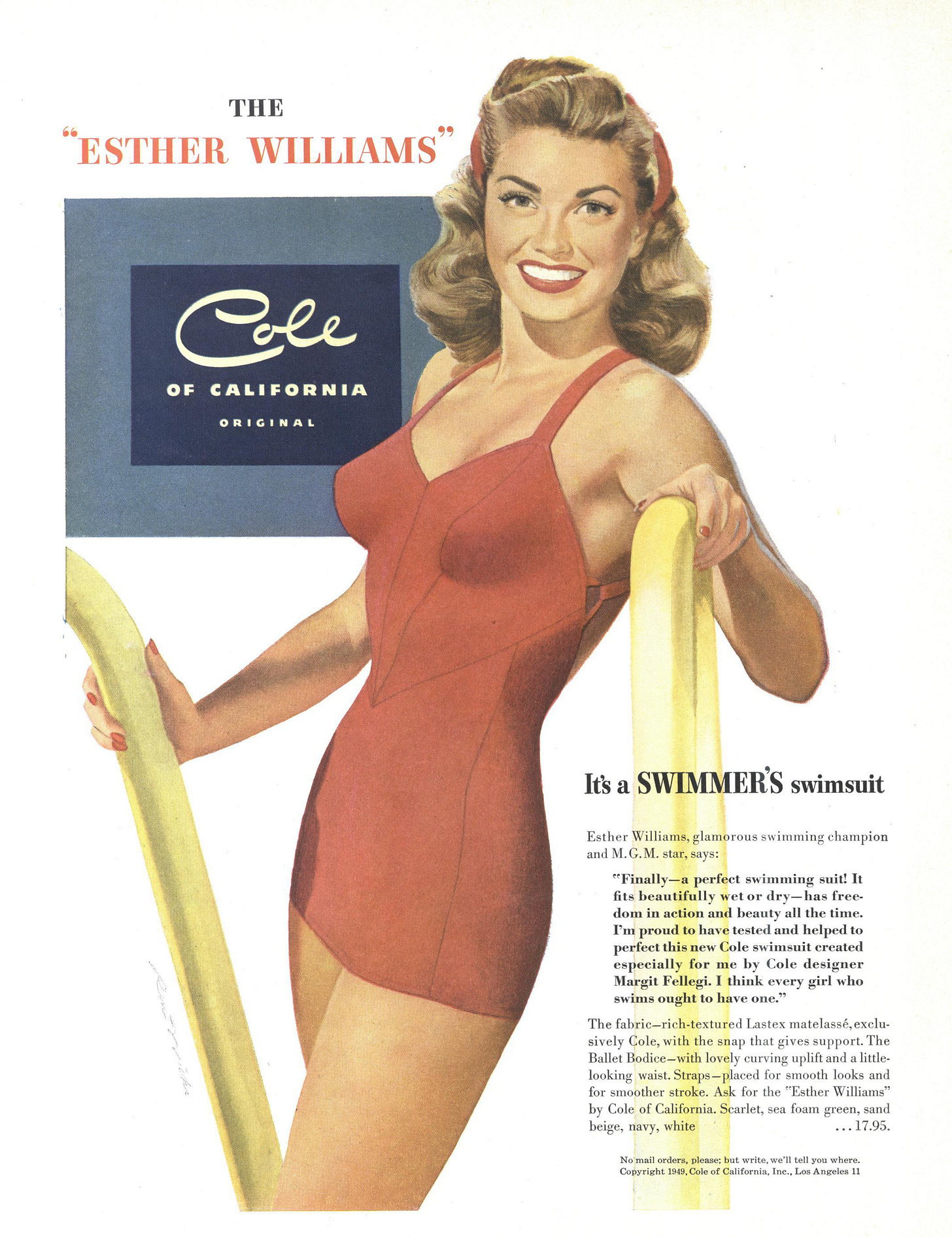

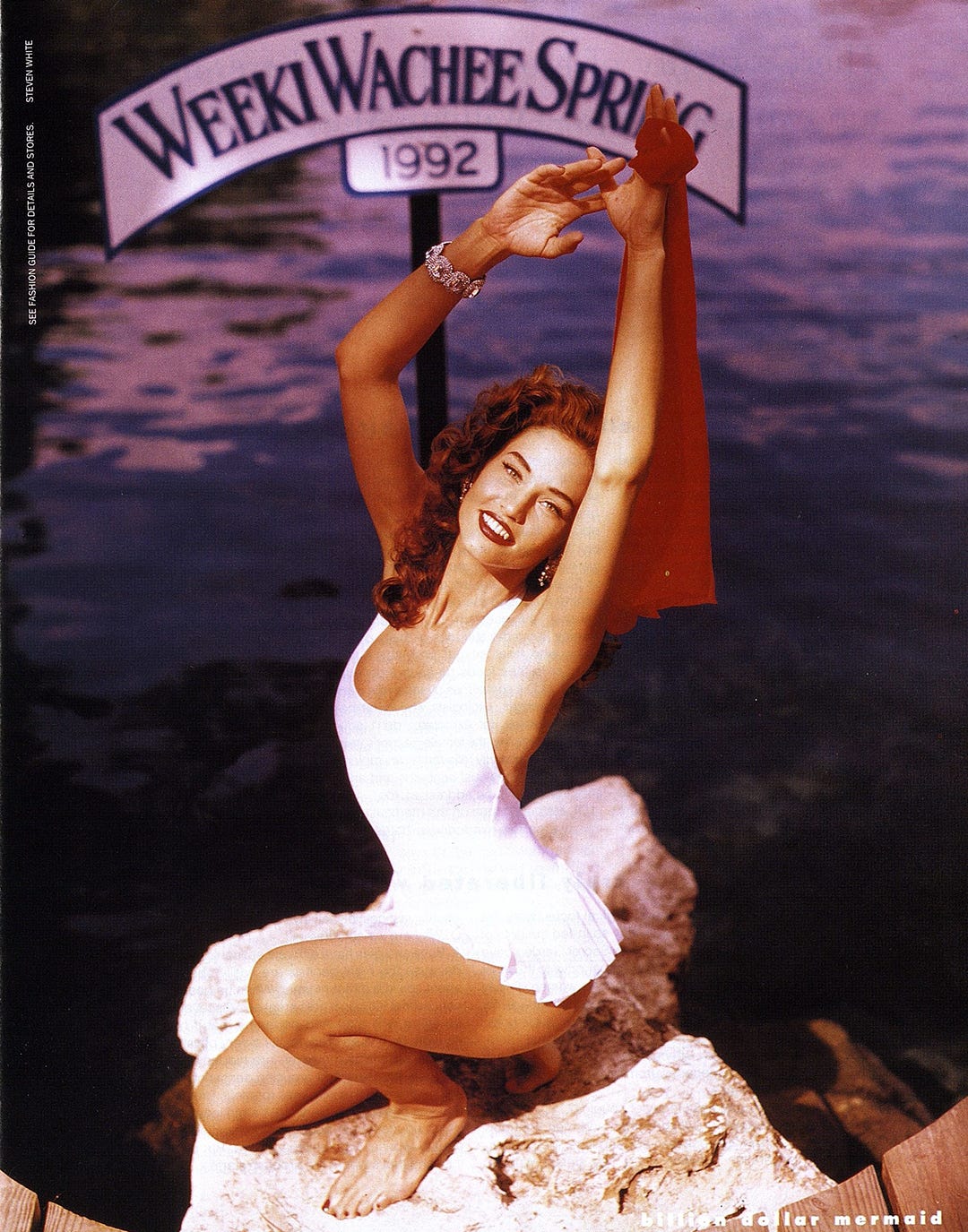

Embodying not just the stereotype of the all-American girl (healthy, vibrant, athletic, and always smiling), Williams also embodied the American ideals of innovation and entrepreneurialism. In 1948, she became a spokesperson for the swimwear company Cole of California, appearing in their ads and designing special collections for them. This led to her later starting her own swimwear line. In 1956, she launched a line of mass-produced swimming pools at prices the average homeowner could afford. She was a highly successful businesswoman, and both the swimsuits and pools are still in production today. The greatest influence of her work can be seen in the recognition of synchronized swimming as an Olympic event in 1984.

Taking a risk as a teenager in leaving her steady job for Hollywood and an untested idea, Williams became a star with far-reaching impact. It wasn’t as an actress that Williams made her mark, nor as a traditional sex symbol (though her perfect body was often on display). Her appeal came not from overt sexuality but rather from an easy, self-assured radiance and good health. In Easy to Love, she was described by her love interest as “all that’s beautiful, clean, decent, desirable, wholesome, and commercial.” Combined with her superb swimming skills and the spectacle of her water ballets, this ensured Esther Williams was like no movie star before or since. Though the aqua-musicals Williams starred in were the creation of MGM, she made them completely her own through dedication, verve, and charisma. No one has attempted to make an aquamusical since she retired from them in 1956, proving that the whole genre was created and existed solely for her, the “aquactress” of all-American dreams.

An Esther Williams-inspired editorial from Harper’s Bazaar, June 1992. The opening page is a photo of Williams; the others were photographed by Steven White at Weeki Wachee Springs.