Edward Durell Stone's Hallmark Gallery

Retail and Exhibition Elegance from the Famed Architect

In the early 1960s, the firm of architect Edward Durell Stone was among the largest architectural practices in America; across its offices in NYC and Los Angeles, there were over 200 employees, including 50 licensed architects, tasked with working on the vast number of commissions that continuously flooded the successful company. The acclaim heaped on his 1954 design for the United States Embassy in New Delhi, India, led to an ever-increasing series of prominent commissions through the 1950s and into the 1960s, both for the US government and for major companies—all seeking the signature blend of monumental formalism and romantic historicism that had caused Architectural Forum to speculate that in 1958, “after Frank Lloyd Wright, Stone was probably the best-known architect in America” (he also appeared on the cover of Time that year). While his designs for projects like the Kennedy Center and the General Motors Building were front-page news, Stone and his firm worked on so many projects annually that it is unsurprising that many of the smaller ones are now long forgotten and long gone. Among these was the Hallmark Gallery in New York City. I first became aware of the Hallmark Gallery by chance—while researching Hallmark’s books divisions I came across an ad that proclaimed, “Edward Durell Stone, the famous architect, has designed the elegant and unusual setting for the exciting collections of unsophisticated art shown in the new Hallmark Gallery.”

Joyce Hall, the founder of Hallmark, had dreamt for decades about opening a New York store (the company has been headquartered in Kansas City since his first store opened there in 1913); he got his wish when, in September 1963, it was announced that Hallmark Cards, Inc. had leased three floors at 720 Fifth Avenue, as part of a new idea for an exhibition-cum-retail environment. On the northwest corner of 5th Avenue and 56th Street, the Hallmark Gallery was to be located on the ground, 2nd floor, and basement levels of a modern building constructed in 1952 by Emery Roth & Sons (for more on the site’s earlier edifices, read this blog post). Previously occupied by menswear retailer John David, Edward Durell Stone was retained to completely remodel the space.

To welcome Hall to the neighborhood, a party was held for him at the St. Regis Library Suite in June 1964 that was a who’s who of important mid-century New Yorkers, all with businesses located close by in Midtown. Hosted by the realtor Peter Grimm and William Ichabod Nichols, the publisher of This Week Magazine, Hall, Stone, and Gallery director Henry Dreyfus were joined by local guests including Cardinal Spellman (Archbishop of New York), The Power of Positive Thinking’s Norman Vincent Peale, Rabbi Seligson of Central Synagogue, Elizabeth Arden, the jeweler Harry Winston, Walter Hoving of Tiffany’s, Lehman Brother’s Robert Lehman, Father Gannon, former postmaster general James Farley, Ambassador Bob Murphy (at the time a director of Corning Glass Works, which had a store nearby), publisher Alfred Knopf, Doubleday’s John Sargent, Richard Rodgers (of Rodgers and Hammerstein), Prince Serge Obolensky, Congressman John Lind, and Henry Luce, among many others.

After eight months of construction, the Hallmark Gallery opened on June 12th, 1964. Edward Durell Stone reworked the façade, all marble and bronze, the Fifth Avenue front now consisting of three glazed arches, 23 feet high. From the street, passersby could look into the windows and down into the lower-level gallery itself. As he told one newspaper, "I've noticed that people are fascinated by looking down. Here in New York pedestrians stare down into sidewalk excavations and Rockefeller Plaza is always jammed with a crowd watching the ice skaters below." He sought to draw people in by exposing not just the elegant store but also the areas below.

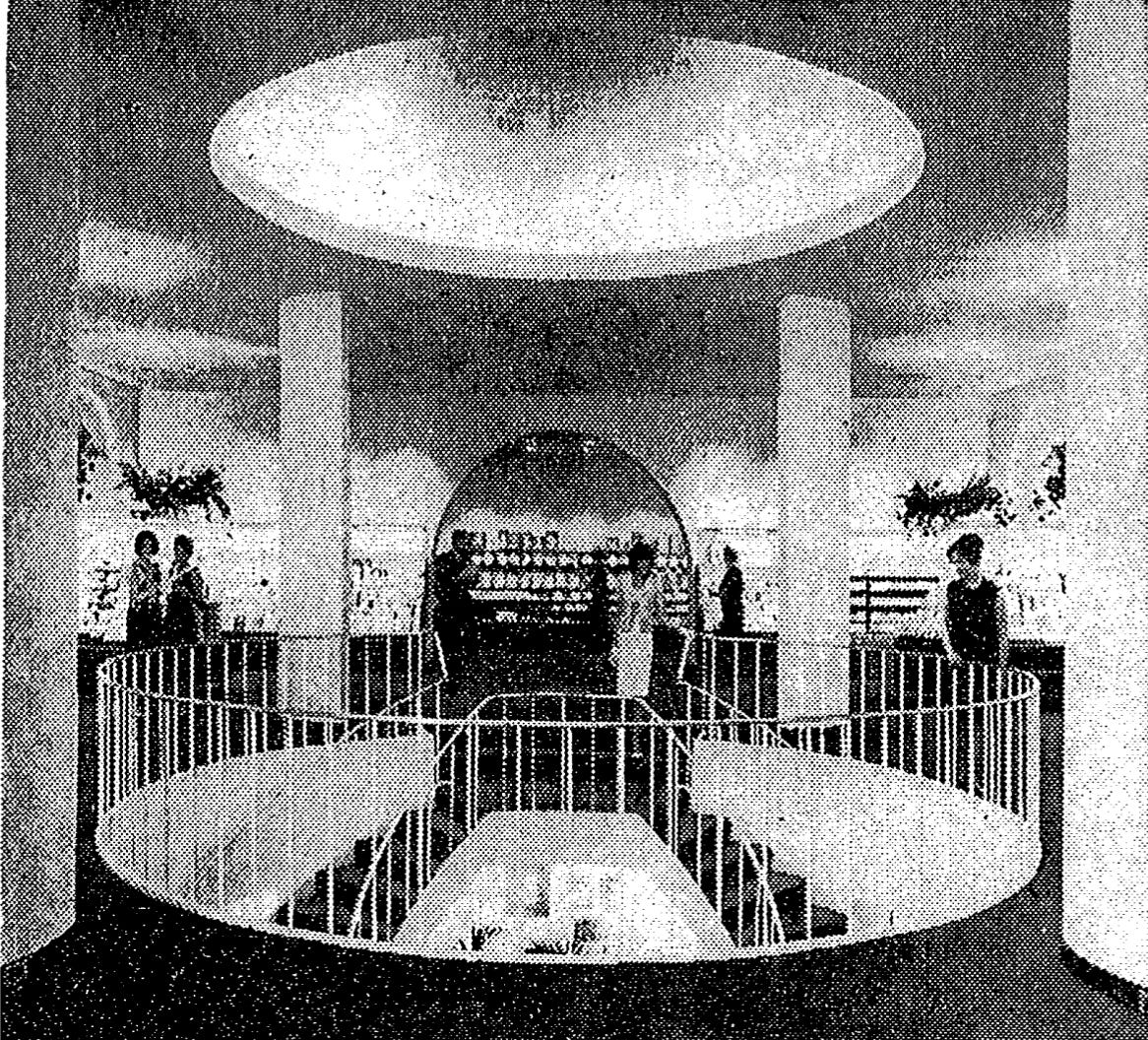

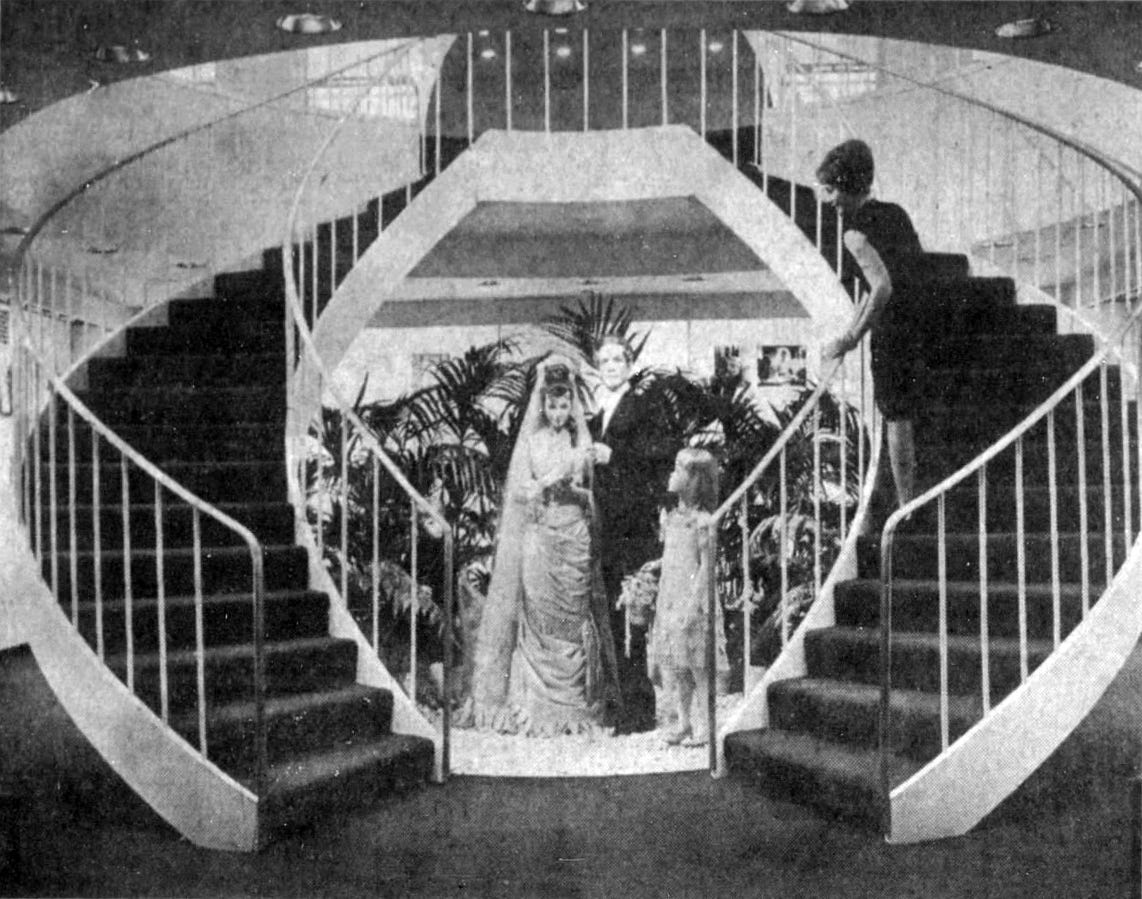

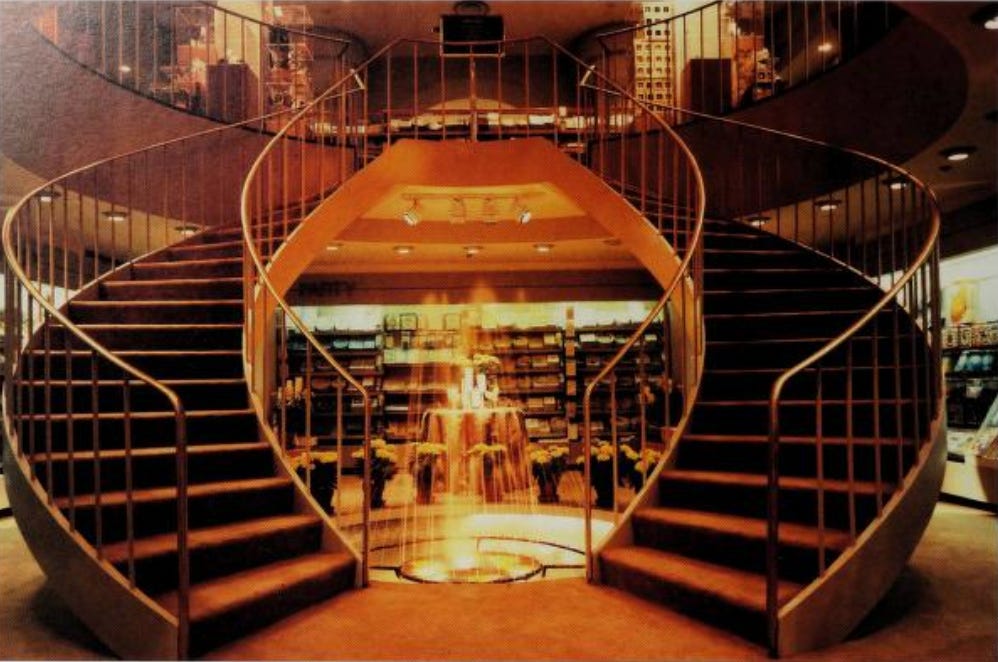

After entering through the center arch, customers crossed a red-carpeted bridge that spanned the 3-story vaulted area. Overhead were three 8-foot hanging “fountain-chandeliers in gilded basins,” which could be “set at varying heights or converted into displays or planters.” Passing across the bridge and under a series of twin arches, visitors entered the retail display area, topped with a gold dome and surrounded by four large elliptical columns. In the middle, a double circular stairwell led down to the exhibition gallery. The red carpet, white walls, and accents of walnut and gold created “an elegant interior color scheme” where walnut-and-bronze “newly fashioned fixtures are arranged in alcoves to display the firm's full line of products, from greeting cards and gift wrap and ribbon, to party goods, playing cards, notes and stationery.” At the ends of each alcove were large bronze bowls, bearing plantings and additional lighting, while a “series of arched niches” were “repeated in the side walls above the card cases, where decorative objects related to greeting cards are displayed.” A screened area at the back of the room, “separated from the main floor by sliding wood grilles,” was set aside for the selection and ordering of custom work, such as personalized Christmas cards and imprinted stationery. Overall, the effect must have been quite stunning; as his wife told an interviewer around this time, "Edward feels that to be architectural, the first thing buildings must be is beautiful. You should be inspired when you walk into them."

Following the double circular stairs down, visitors first took in a fountained pool set between them. The whole lower-level exhibition hall was 2,100 square feet comprising three areas that could be partially screened off or opened to form one large space. Around the fountained pool was a square room that contained the continuation of the four elliptical columns from the main floor. Next was a “long rectangular gallery with a coffered ceiling developed to provide an unusually flexible degree of lighting.” Along Fifth Avenue was “the three-story, vaulted area visible from the street and the entrance bridge.” A system of movable wall panels had been designed for the mounting of display material to “provide an exceptionally versatile arrangement few museums can boast.”

Not everyone loved it. Writing in the New York Times, architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable had nothing good to say about it:

This is one of those jobs that one wishes the able Mr. Stone had never done at all. The ground floor of a conventionally ordinary ribbon-windowed office building has been transformed into an arcaded shop with cookie-cut arches, hanging planters, a bridged-over exhibition pit, curving horseshoe stair, gold-leafed domes and crimson carpet. The foliage is real and the music is canned. It takes all of the traditional trappings of elegance and turns them into, not elegance, but a caricature of it. This is pretentious, and pretention is vulgarity in any language.

Hallmark avowed that the store was experimental, not meant to be a competitor to the local drugstores, variety shops, and other venues that sold their cards. Instead, it was to serve as a kind of incubator on retailing cards; as gallery director David L. Strout told the New York Times, “We think there are many new and important lessons to be learned, of benefit to the entire industry, from merchandising greeting cards under the most favorable circumstances we can devise” (hence the luxurious surroundings and custom-made display fixtures). With more than 2,000 cards always on display, the gallery was designed as a "total merchandising concept" coordinating “such factors as architecture, decor, traffic control, display and stock control.”

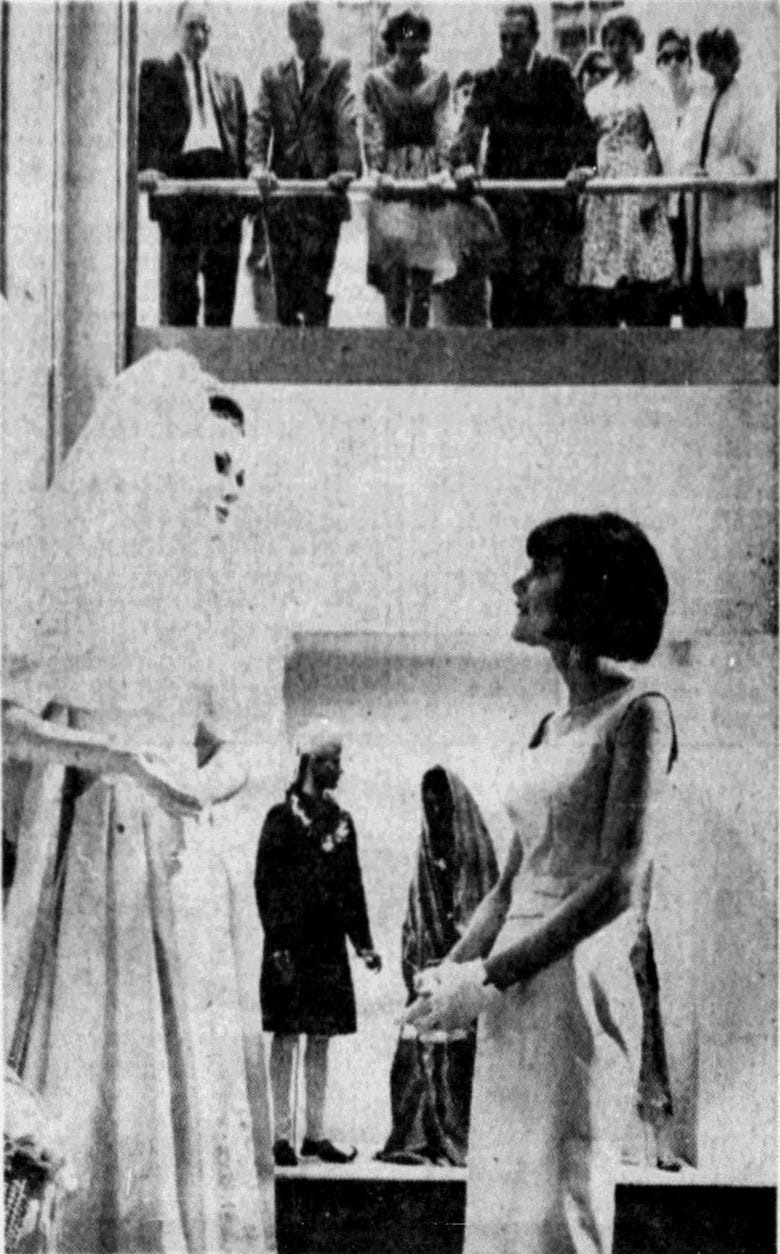

Early ads boasted “The red carpet is out on Fifth Avenue,” inviting New Yorkers to take in Stone’s “new kind of art gallery.” It was to be a showcase for “the unusual collection of fine art, folk art, and graphic art from around the world. A collection that reflects the Hallmark interest in many areas of good taste, design and communication.” The opening exhibition was “The Art of the Wedding,” which was advertised as “not a ‘Brides Only’ show, but a collection of fascinating things. You will see the kind of ring brides wore in ancient Rome—and the kind of wedding gown they will wear next year. You will find strange and wonderful things from around the world—from primitive and civilized traditions. And each item is filled with special meaning.” As the ad continued, “What has this to do with Hallmark Cards? Everything. They are all part of this new world of art. That is why Hallmark is giving New York this different kind of gallery.” Gallerygoers were greeted at the base of the stairs by mannequins dressed as a Victorian bride, groom, and flower girl, standing in front of a jungle of palms, and posing for a photograph taken by another mannequin complete with a huge antique camera lent by the Eastman Kodak Museum. Visible from the avenue was a modern bride surrounded by wedding tableaux from other countries, and flanked by tables displaying traditional wedding cakes and breaks specially baked for the exhibition. “The paneled walls of the exhibition area contain a fascinating collection of wedding photographs, old rings, goblets, scrolls, marriage contracts and other objects associated with the wedding ritual.” This mix of types of objects and displays was to be found in most future exhibitions throughout the Hallmark Gallery’s lifetime, reflecting the gallery's mission statement of showing “unsophisticated art.”

“If you think Art is something that must hang on a wall or sit on a pedestal, come let us show you a whole world of Art you may have missed. The Art in the new Hallmark Gallery is a reflection of people—all kinds of people—and the lives they lead. It springs from the pleasures, customs, beliefs, and hopes of people in many times and places.” - Hallmark Gallery ad

Not every show was “unsophisticated”—among the exhibitions in the first year were 141 photographs by Harry Callahan, which Hallmark acquired as the first pieces in what would become the Hallmark Photographic Collection, one of the earliest corporate photography collections (it was donated to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, in December 2005). Other photography shows followed in the coming years, among them Henri Cartier-Bresson, Andre Kertesz, Toni Frissell, and one of Magnum photographers (tying in with the book, Peace on Earth).

By 1969, the Hallmark Gallery received more than 250,000 visitors annually, with six to eight exhibitions per year, each running for around six to eight weeks. The gallery was always free so the shows generally leaned towards being crowd-pleasers—themes that could be explored in a multitude of ways, often featuring recreated spaces. Isabel Forgang of the Daily News explained how, “Once an exhibit idea is decided upon, a Gallery research team goes to work visiting libraries, museums and antique shops, learning the subject and gathering material. The exhibits are assembled in a barn-like workshop in a town called Vista, outside New York and then trucked to the Fifth Ave. Gallery.” For example, a tribute to the rose, “its history, genealogy and its influence over the ages upon literature, art, music, design, symbology, legend, medicine and food” included “a reproduction of an old-fashioned apothecary shop featuring medicines and fragrances extracted from roses, a copy of the famed rose window of the Cathedral of Rheims and a 26-foot turret fashioned after the famed kiosk of the Empress Eugenie at Bagatelle, in Paris,” as well as a 28 million-year-old fossilized rose.

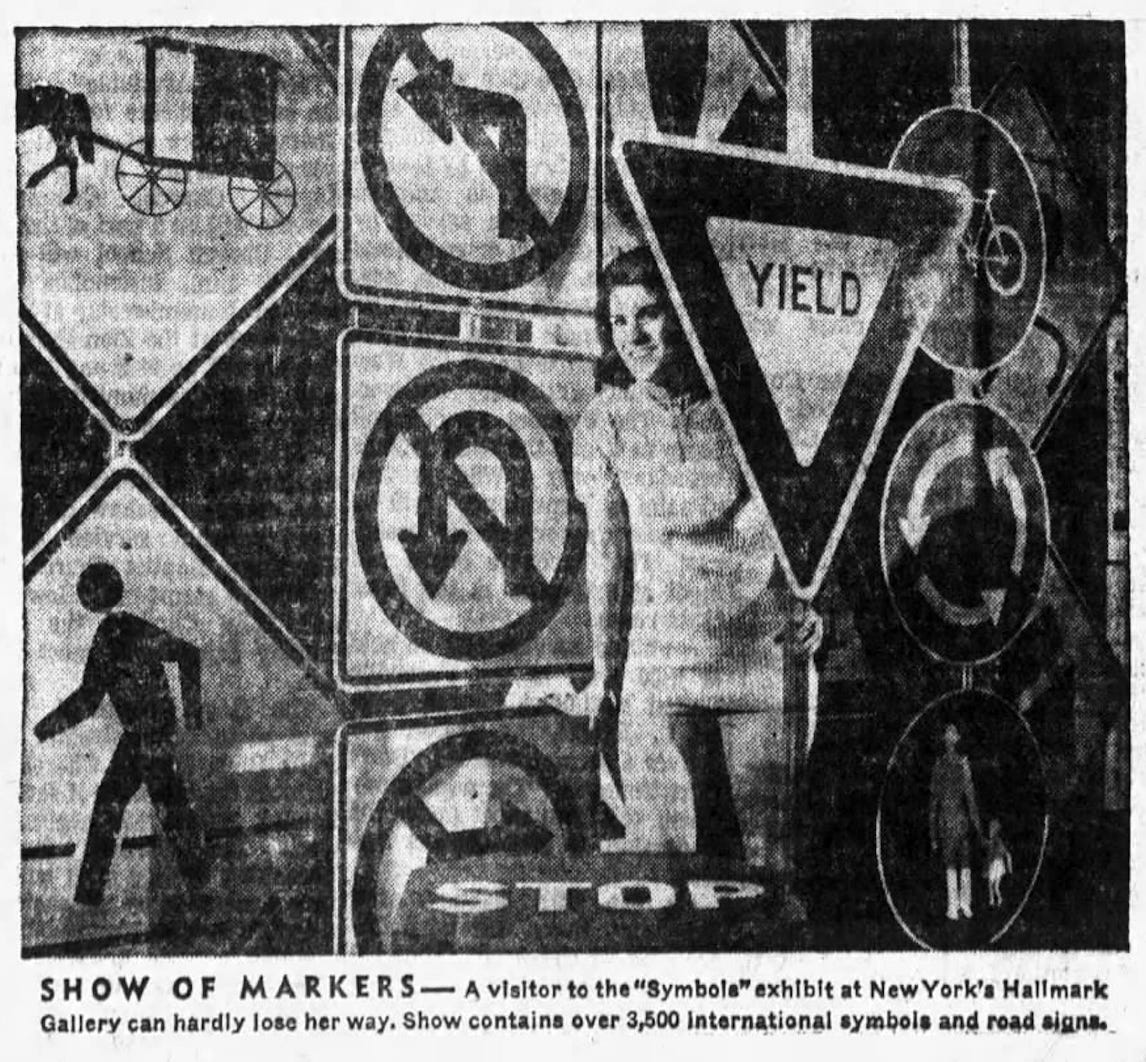

The emphasis was often on exhibitions that appealed to the whole family: antique toys, circuses, “Cityfair” (“Puppeteers, singers, musicians, craftsmen doing their thing”), “Signs of the Times” featuring 1880s to 1920s trade signs, symbols, and neon were just some of the many fun themes that drew in crowds. Photos show visitors touching, feeling, smelling, and exploring the objects on view—the Hallmark Gallery was an early innovator of interactive exhibitions. If the exhibition was about the history of bread, fresh loaves were brought in daily; for a show on Ireland, “the smell of the turf fire and the pot oven soda bread” were piped in. “Garbage,” in 1971, showed how trash could be “reused (or, as it's more chic to say in garbage circles, recycled) into everyday items such as home accessories, furniture, almost-jewelry and whimsical wall décor,” complete with a mock-up living room with furniture made from recycled paper and cardboard where visitors could lounge. An exhibition on the history of Easter eggs held daily lessons on the art of decorating them, with different artisans teaching techniques from all over the world, while a quilting exhibition had on-site quilters every day, ready to answer any questions.

Shows with workshops directly aimed at kids were also popular. "Kaleidoscope" in 1971 was described as “a spacious room, asplash with vivid exhibits and a colorful, jumbled workshop where children can make things to play with and then take home… Many will stick to the workshop area where hip-high tables, laden with swatches of felt, yarn, burlap, plastic, bowls of melted colored crayons, piles of paper and cardboard forms await the neo-artists. Here young visitors can make jewelry, crazy fun glasses, puppets, posters, banners, pictures or satisfy any other creative ideas that might pop into their heads.” It was so popular that a limit of 45 minutes had to be put on every group of 50 children (adults had to watch from behind a fence).

The Hallmark Gallery closed after twenty-two years on Christmas Eve 1986. As a showplace, the Hallmark Gallery exemplified Joyce Hall’s oft-quoted belief that “Good taste is good business,” but it was barely a break-even proposition for most of its existence: expensive real estate, glamorous setting, and costly exhibitions, all for free. Thousands of people might have been lured in weekly to see the shows, but the percentage who also purchased cards was likely small (especially considering the fact that the Hallmark Gallery was always included on lists for tourists of how to visit NYC on a few dollars a day). I’m unsure when the facade was remodeled, but no sign of Stone’s work remains. For many years, 720 Fifth Avenue hosted an Abercrombie & Fitch store; Prada, whose NYC flagship is next door, purchased 720 in December 2023 for $410 million.

For a store/gallery that welcomed so many people and was widely described as “beautiful,” very few photographs survive. The Hallmark Gallery isn’t even listed as a project in the Edward Durell Stone Archive at the University of Arkansas. A gorgeous interior by a famous architect that likely entertained millions of people over two decades is now forgotten.

Thank you to Bonnie for alerting to me to these two photos of the Hallmark Gallery in colour, from the book, Hallmark: A Century of Caring, available to view on the Internet Archive.

Some other photos from exhibitions held there:

Beautifully written and researched article! The themed exhibition concept is so fun. Your note about wanting to find color photos led me to track down this book "Hallmark: A Century of Caring" on the Internet Archive that has color photos of the staircase and the exterior on p. 146: https://archive.org/details/hallmarkcenturyo0000rega/page/146/mode/2up?q=%22hallmark+gallery%22 It also mentions that Stone designed one of the Hall's department store locations in KC. So cool!

This article feels like a slippery slope of falling into any of these exhibitions. Thank you.