When I came across this image in a 1952 issue of Town & Country (which I posted to my Instagram earlier this month), I knew I needed to do a deeper dive into its location: the Coty Salon in Rockefeller Center, designed by Dorothy Draper. As I’ve written here before, Draper was one of the most important American interior designers from the 1930s to 1950s—her trademark strong color, exciting contrast, and oversize scale led to the genesis of Hollywood Regency style.

Raised in the high-class milieu of Tuxedo Park, New York, Dorothy Tuckerman was instilled with “an innate sense of entitlement and authority” that, along with her deep understanding of historical interior styles from the family’s annual trips to Europe, laid the groundwork for her to become a design authority. After her marriage, she became known for having a flair for decorating—as her influence grew within high society circles, Draper founded an interior design business in 1925. Draper is said to have considered her lack of formal education an asset; “You don’t have to know anything about a subject as long as you use common sense and imagination, plus enthusiasm! I use all periods of design in my work, for, after all, decorative styles are simply indications of a manner of living. There are only three things to remember in decoration: comfort, color and a grand enough scale.” From coast to coast, Draper was called on to redecorate legendary hotels, using her decidedly anti-maximalist aesthetic to remake them into larger-than-life spaces that were as awe-inspiring in photos as they were in person. In 1941, when Coty (a French perfumier and cosmetics company) took over a space in Rockefeller Center’s La Maison Française (610 Fifth Avenue), they called Dorothy to help them.

One of the original buildings of the Rockefeller Center complex, La Maison Française was designed by the Center’s lead architect, Raymond Hood, and completed in 1933; it is the twin of the British Empire Building directly to the north. Together they form the International Complex, along with the International Building skyscraper. The six-story Art Deco building housed the French consulate (until 1942) and a number of French businesses. Coty took over a two-floor space at the corner of Fifth Avenue and Rockefeller Center Promenade.

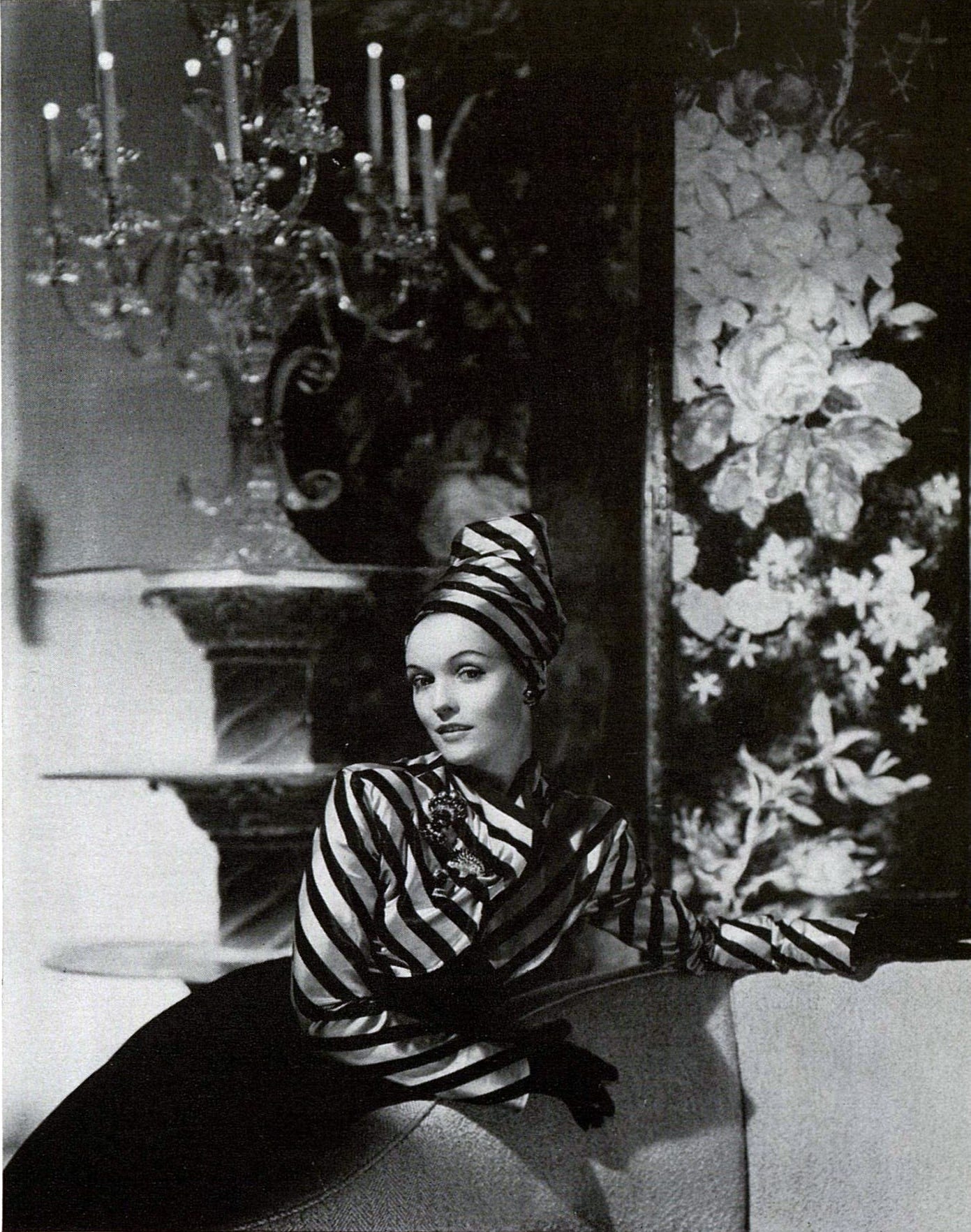

Taking as her inspiration the colors of both France and the United States—red, white and blue—Draper redesigned the space in her trademark neo-Baroque style. Called a “jewel box” by the New York Times, walls painted a soft porcelain blue intermingled with wide expanses of mirror framed with deep chintz borders. Draper hung the windows with nubby gray silk and snowy white mousseline. “Deep grayed blue carpets completely cover all the floors, and woodwork, winding staircases and showcases are painted to match.” Atop the carpet sat carved wooden chairs, painted white and with soft red leather seats, and tall black screens “lacquered with exotic red roses and mother-of-pearl leaves.” Along a make-up bar were individual mirrors in pale blue carved frames. The whole space was lit by white tapers in Venetian glass candelabras, placed atop white carved columns segmented with glass rounds.

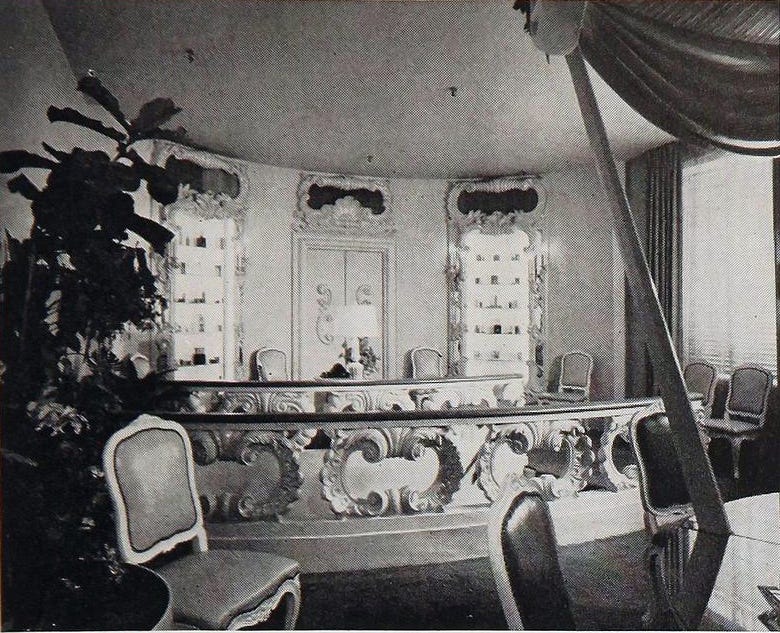

At the bottom of the grand, ornately carved white staircase, a bed of red geraniums and other plants—the curving, pale blue carpeted stairs leading upstairs to the mezzanine, “the background is of frosted blue, accented with dashes of black lacquer, white, and cherry red.” To one side was a perfume bar; described as “The Tent—perhaps the gayest and most unexpected bit of décor in the whole brilliant scheme. Its spirit is pure carnival, carried out in white satin with great bouquets of red roses and looped ribbons, around a center pole of plaster with shelves on which Coty products are displayed.” Beneath the tent was a circular mirror-covered bar (also painted pale blue), around which customers could sit (on white chairs with pale blue cushions) while trying different scents. Throughout the space, surrounding doors and as balustrades, were the overscale scroll-and-shell plasterwork so associated with Draper’s neo-baroque, often surreal style—all of this plasterwork was made for Draper in Brooklyn by a family firm named Cinquinni.

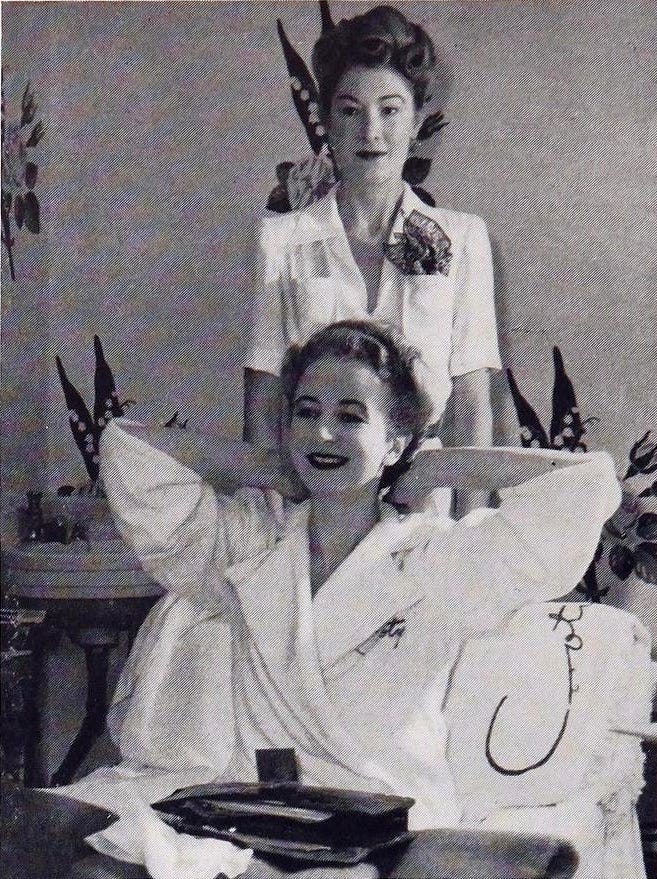

Also upstairs were a series of small treatment rooms, each named after the flower enlarged across its walls—the Lilac Room, the Rose Room, the Tulip Room, the Fuchsia Room, and the Lily of the Valley Room. Inside were “giant white fringed chairs for relaxation and tall white plaster trees holding the complete Coty beauty program of creams, oils, lipsticks and powder puffs,” with white fringed rugs scattered on the floor.

Coty knew Draper had created something special. Their ads proclaimed, “COTY makes its contribution to New York’s soaring reputation as THE WORLD’S FASHION CAPITAL!” They called it a “new kind of salon, more a source of inspiration than a shop…the fountain-head of style and beauty news.” While the US had yet to enter WWII, patriotism was the advertising push of the moment, with Coty declaring that customers would leave “with a sense of its warm hospitality…with a new conception of beauty…with a firm resolve of your own to contribute to the chic of American Womanhood!”

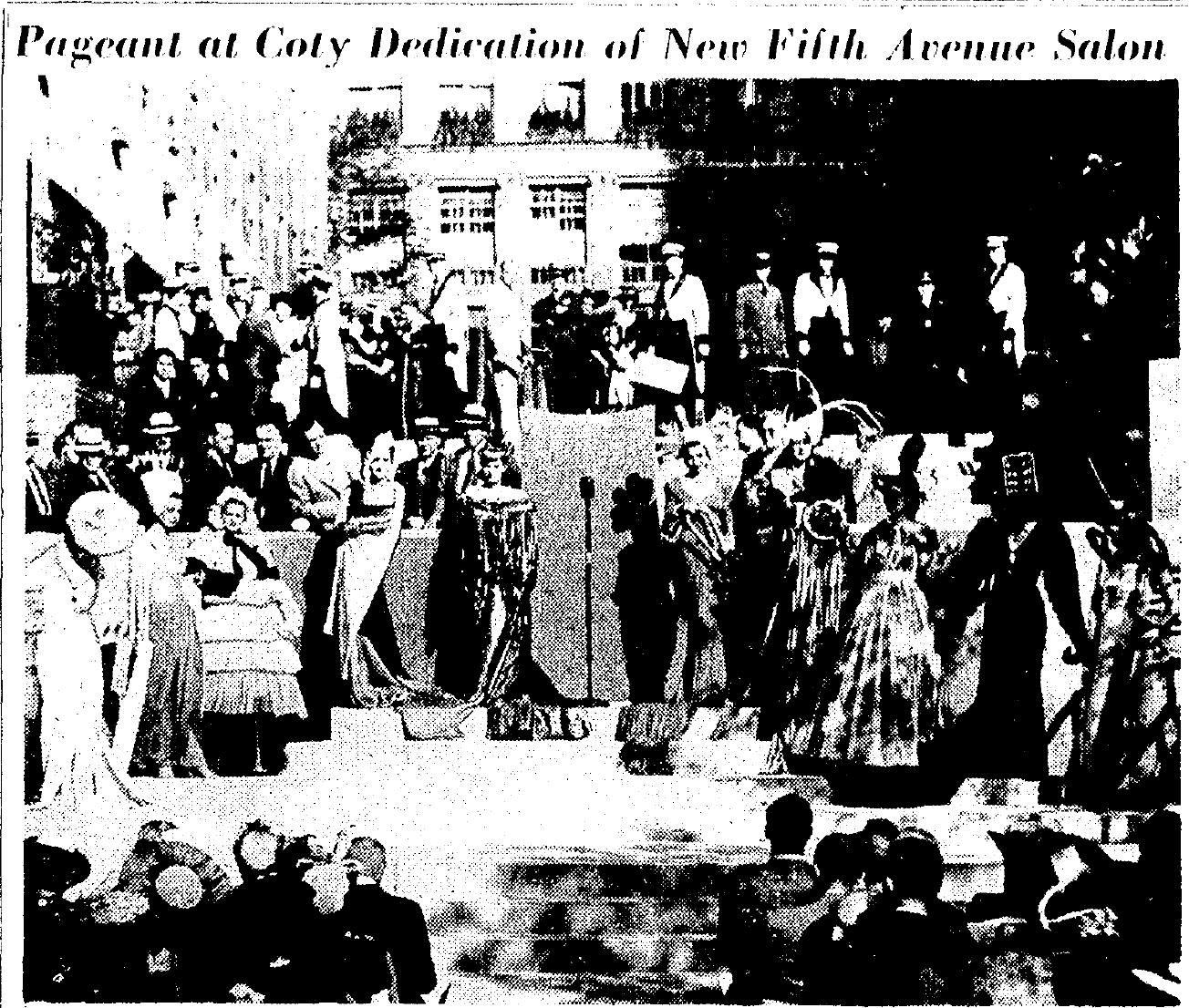

A pageant opening, “Beauty is a Joy Forever,” was held on July 9th, 1941. According to the Herald Tribune, thousands of onlookers filled Rockefeller Plaza to see models parade down a central open-air runway. Made up using Coty cosmetics and modeling New York-designed fashions, the fashion show sought to bring to life the fantasy of Coty’s products. The first interval showcased groups of daytime, evening and sports clothes sold by B. Altman, Mary Lewis, Stern Brothers, and John Wanamaker; the hats came from Lilly Daché (wife of Coty’s executive vice president), while the jewels, many of them historic pieces, were from Trabert and Hoeffer-Mauboussin. The models also appeared in uniforms reflecting the various branches of defense work that American women were widely active in.

The centerpiece of the pageant was a “dramatization of ten of Coty’s best-known perfume fragrances” designed by Lester Gaba. Gaba was a sculptor (best known for his incredibly life-like mannequin, Cynthia), retail display designer, and the author of Women’s Wear Daily’s column, “Lester Gaba Looks at Display,” which ran from 1941 to 1967. Among the costumes he designed for Coty were “Paris,” a “1910 waltz gown of cerise satin, with plumes nodding in her hair”; “Styx,” a “fantasy of black and satin, sequins and coq feathers”; and “Muguet” was “demure in layers of tulle and lilies-of-the-valley.” The model Suzanne Sommers “trailed a pink silk jersey train and an aroma of Jacqueminot, her figure-molding gown and her scarf and hat of airy pink tulle suggesting the rose for which it was named,” while Gay Harden wore “flame-colored silk jersey, with long gold kid gloves and a headdress of the flame color and gold, flourished a huge gold magnet from which dangled tiny figures of men—symbolic of the lure of ‘L’Aiment.’”

Following the fashion show, two special ballets were performed featuring a dozen Rockettes and a few of the Corps de Ballet of Radio City Music Hall. The pageant ended with the coronation of two ideal American beauties—one blonde, one brunette—selected in a national contest. Metropolitan Opera star Rose Bampton sang “The Star-Spangled Banner” before crowning the beauties with twin ruby studded crowns, Napoleonic originals from Trabert and Hoeffer-Mauboussin’s collection. After the pageant, City Council President Newbold Morris cut the ribbon at the entrance to the salon, and, following a Coty tradition, a bottle of perfume was smashed on the front steps.

Draper’s original interiors survived with few changes into the 1960s—that 1952 Town & Country image revealing a change of upholstery to black silk brocaded with multi-colored flowers and leaves. After twenty-five years, the Coty Salon was redecorated—and renamed, the Coty Showcase—in 1966. Jeanne Hunt Miller, a package designer for Coty, was behind the gut renovation. By that time, Draper was retired; she passed away three years later, at the age of 79.

Can’t help but feel we have pulled so far away from this kind of beauty standard. The attention to detail, opulence and class seems like a distant memory. Thank you for sharing, I truly enjoyed reading this.