Yesterday, I released a new episode of the Sighs and Whispers podcast talking with fashion designer, actress and model Edina Ronay. Born in Budapest to a family of successful restaurateurs, Edina Ronay fled to London with her parents after the war. There her father opened a restaurant and then founded what became a very successful and influential series of guidebooks, starting with Egon Ronay's Guide to British Eateries in 1957. As a teen Edina became an actress, appearing in a number of cult British films. She was a key member of the hip London scene and dated Michael Caine before she met her husband, Dutch film producer (later photographer) Dick Polak. Together they lived a hippie lifestyle in Morocco and Formentera, before returning to London to act, model and have children.

In the early 1970s Edina began selling vintage clothes. This led to her starting a knitwear label based on vintage knitting patterns, which eventually grew into her own fashion label. Edina Ronay showed at London Fashion Week and was sold all over the world. Throughout her career, she was at the center of swinging and creative London. We cover all of this and more, including her over 50-year marriage, motherhood and spirituality.

Listen and subscribe to the podcast in iTunes

Listen and subscribe to the podcast on Spotify

Listen and subscribe to the podcast on Stitcher

I’m working on some longer, research-heavy pieces for the coming weeks so here’s a little something different…

A two-part look at the homes of fashion designers published over the August and September 1969 issues of Town & Country. The first issue featured European designers, the second American. Today I’m sharing part one with you; part two will be in my paid subscribers email on Friday.

Interiors and dress as a form of self-expression are irrevocably linked. Not to say that all that are interested in one are equally interested in the other—the same goes for those with talent—but there is generally cooperation and agreement between them, as well as a similar pattern of trend dissemination. The process of fashion designers—who spend their time engaged with questions around covering and exposing the body—formulating their philosophies of the home is an intriguing one. Sometimes there is true alignment between their philosophies of dress and home, while for some there appears a total disconnect.

While each designer only garners one photograph each, the short accompanying paragraphs are loaded with information that will interest anyone interested in fashion, interiors and home trends. For the most part, the homes are traditional. Where there is modernism, it is of the slickly space-age rather than the minimalism of MCM. Dare I say it, but aren’t the interiors more appealing than the dullness of today’s watered-down mid-century “Scandi vibes”? These are homes for living, for entertaining friends, for a gracious existence.

These photos and captions are hopefully thought-provoking and inspiring. Which one would you live in?

Town & Country, August 1969. Story produced by Hermine Mariaux and Thelma Sweetinburgh. All photographs by Ronny Jaques except where noted. Spelling and punctuation all original to the text.

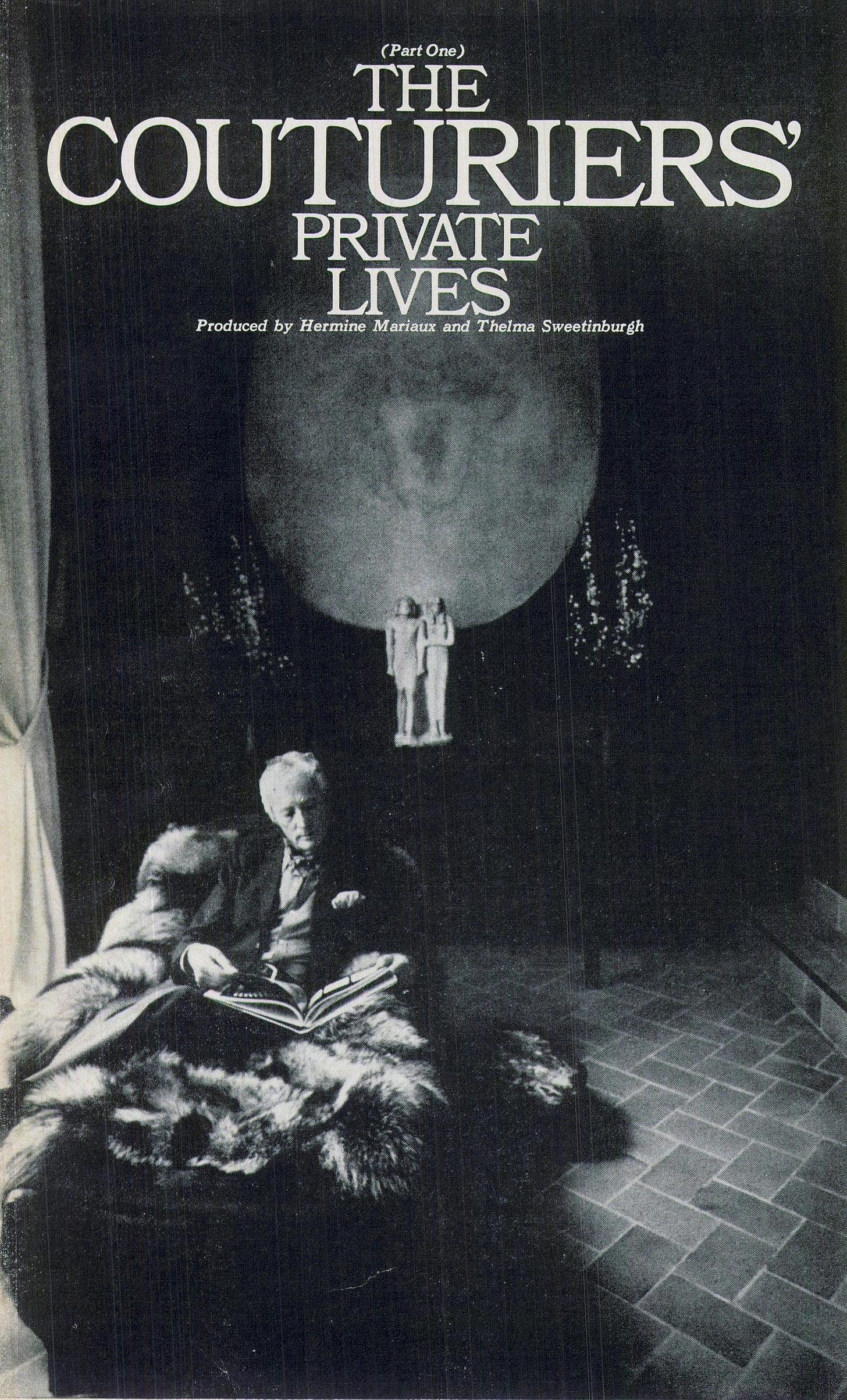

Roger Vivier

A Man of Property. He takes pleasure in possessions. He loves to collect and does it well. With the same unerring eye that makes him one of the world's most creative shoe designers, he places an explosive pink Cesar "expansion" above a Louis XV caned settee, ancient Egyptian statues under an abstract canvas by Dimitrienko, and an Art Nouveau figure alongside a 16th-century coral bibelot on the bluest lapis lazuli of an 18th-century table. When he cannot find what he wants in furniture, he designs it—such as the oversized black leather sofa in the living room and the triple-length glass table. Roger Vivier's basic principles in decoration are the same, he says, as in shoe designing: soberness of line and the choice of either the classical or the extravagant. Both are richly represented in his collection, ranging in scope from the ancient and primitive to the most modern art. Favorite colors are neutrals, except for red. The very first piece Roger Vivier ever bought was a Venetian vase. He recalls: "I was fourteen and found it in the Flea Market. Though genuine, I must admit it was a horror." His first paintings were those of Poliakoff and Atlan, but the most prized is the Francis Bacon. Something he will never buy: kinetic art. "It will not last and is only a nest for dust."

Pierre Cardin

The Pacesetter. He says "I must completely redo my apartment." From the glassed-in gallery filled with trees, which holds 160 seated guests for dinner, one looks out onto the Seine and a moored houseboat which Cardin owns and lends to young artists. "Also, it completes the view," he adds. The décor of his duplex, spacious and sumptuous, with a fin de siècle flavor, echoes the atmosphere of his couture house on Faubourg-St.-Honoré: moss-green walls, wide-striped velvet in deep colors for club sofas and chairs, and somber black Louis XV Boulle furniture. But now Pierre longs for an all-modern atmosphere in keeping with his fashions and latest boutiques, which were done in shiny lacquer and steel by the three Bini brothers.

Manuel Pertegaz

A Man of Contrasts, he creates an environment in which 12th-century art coexists happily with 20th-century plexiglass; ancient Roman and Greek artifacts with modern Scandinavian sculpture; 14th- and 15th-century furniture with abstract paintings. He says that you can judge a man mainly by two things: one is his work, the other is his house. Pertegaz likes his house to be a combination of many things and many feelings. Therefore it represents different things to different people—a refuge to one, a showplace to another. To Pertegaz himself, a sanctuary enveloped by his vineyards. He successfully resisted the temptation to turn his rustic Roman structure into a castle. Instead, he applied utmost simplicity. And yet, admittedly, he worships luxury as long as it is well concealed. He cites tactile textures such as fur, candles, big fires, simple peasant foods, a potpourri of scents as essential elements of luxurious living along with the most important: comfort.

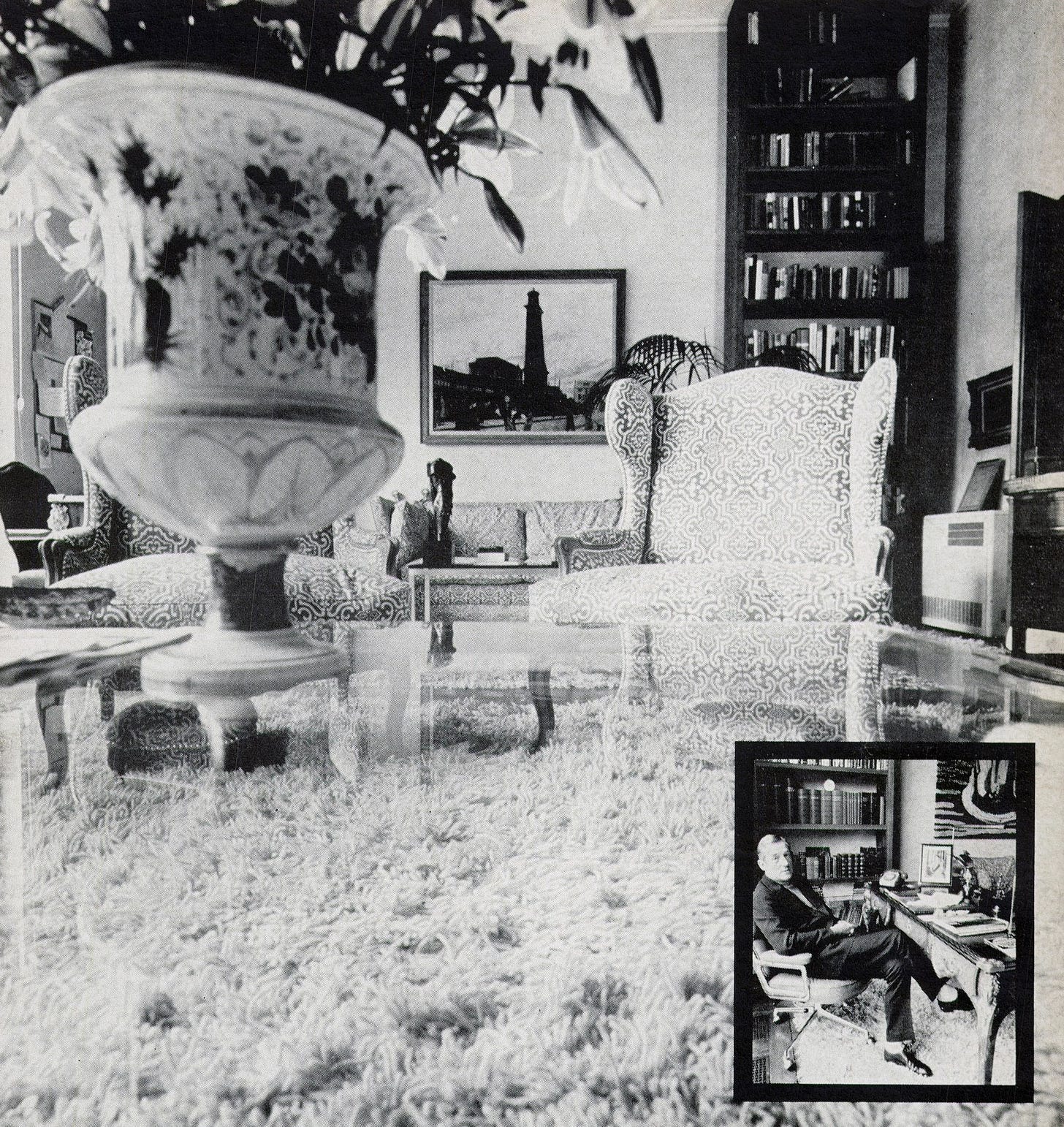

Hardy Amies

A Man of Many Worlds—is loyal to friends, classic concepts, and personal collectibles he couldn't bear to part with. His basic conservatism is matched by quiet surroundings. Design interest is mainly in the variety of tone-on-tone textures. "Texture is the main reason why I enjoy working with men's clothing," states the designer, adding "I like the matness of suit against the silkiness of tie, next to the coolness of shirt." A man of 20th-century contradictions, he collects old master drawings on the one hand, yet is fascinated by the space age on the other. He loves history and opera, yet he designed clothes for the movie "2001—A Space Odyssey." He wouldn't travel anywhere without a book, yet he shuns best sellers. He appreciates the gleam of Knoll's steel-and-glass table and the shaggy texture of his V'Soske rug, yet combines both with late 18th-century Rockingham porcelain, a 12th-century Buddha, and a Louis XIV desk resplendent with ormolu.

Emanuel Ungaro

The Space Seeker. "No more walls, no more doors," declares Emanuel Ungaro, wiping out the past. In his ideal world, his thoughts must be allowed to wander. "No boundaries, no off-limits sign such as tradition provides, but a freeway for my mind. In a house furniture is an obstacle, and in my new apartment there will be none," he promises. Instead, he insists on the importance of total environment. "It puts emphasis on space and on materials—carpeting climbing walls, white stratified panels, earth-brown mirrors are enough to define space." He sees seating, sleeping, and eating practically at floor level in the Japanese style.

Marc Bohan

The Diplomat. To live and let live is Marc Bohan's way of life. Surveying his living room, he says: "Now I would like everything much more modern." His solution is to add fun and motion—an iron contrivance by Tinguely and a giant bird by Niki de Saint Phalle. Shortly, one of Niki's Nanas is to take its place. Cigar-brown leather for deep sofas, sand-beige jersey for Mourgue ottomans, a zebra skin, a white Fontana painting, ebony for the large low Italian lacquer tables form the neutral background. "The problem is properly to accent antiques such as my Boulle furniture," comments Bohan, adding "they are difficult to fit into modern décor."

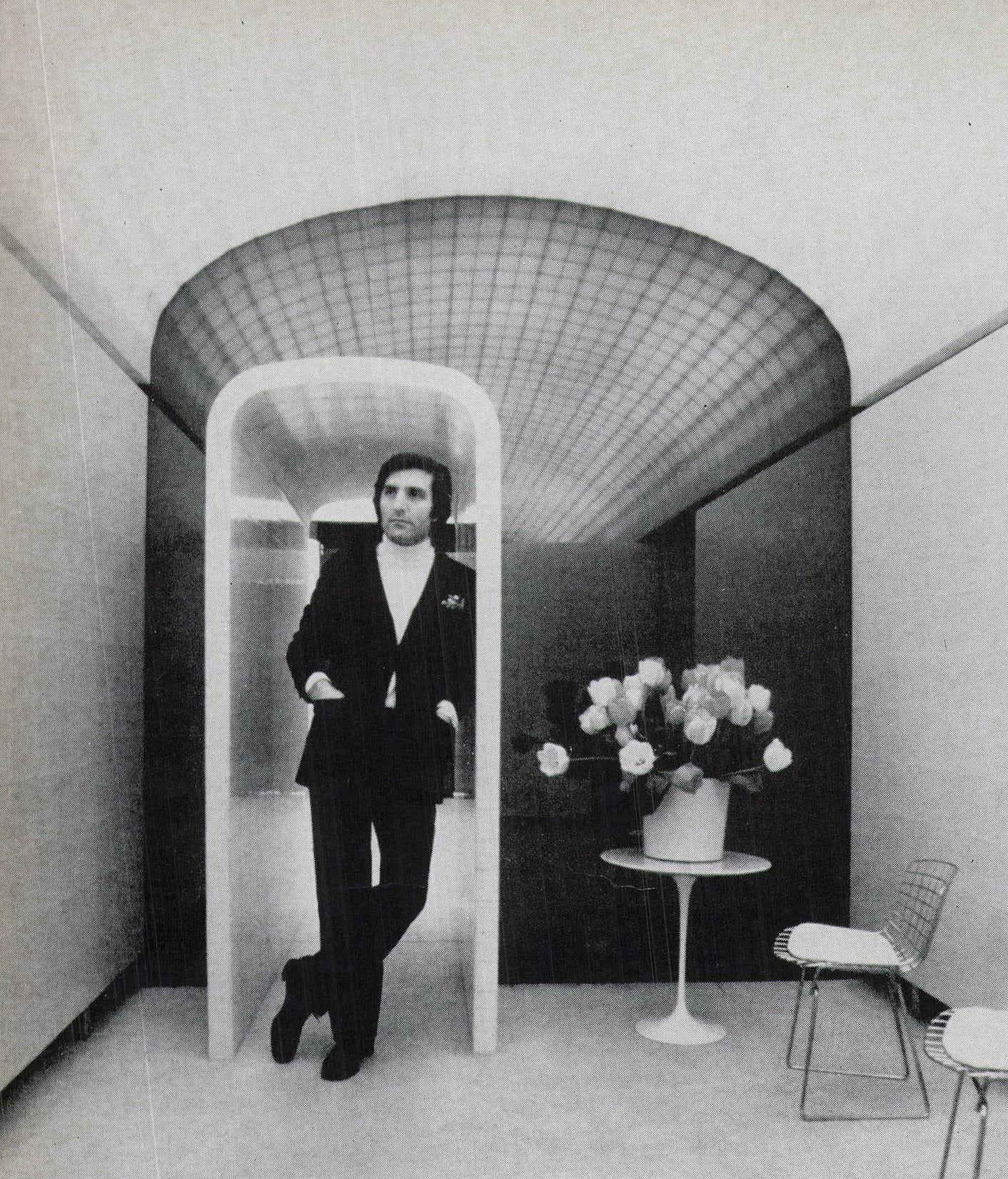

André Courrèges

The Total Man. He does not design anything without thinking first of the way we live: of the impact of jet travel, audio and visual communications—which, he says, shape his thoughts as automatically on fashion as on architecture and interiors. "The present is so dynamic; there is no room for the past in our lives. This is why we need radically different clothes and radically different surroundings. In interiors we need completely to rethink spaces. There is no reason why there should be separations for the merely temporary activities of sleeping, dining, food preparation, and so on when any and all of these can be done in one large beautiful open space, usable for 24 hours of living. I would like to be responsible for designing everything that fits into my concept of 'La Vie Courrèges.' First and always I would be concerned with architecture. My idea would be completely pure spaces, all white inside, furnishings invisible, as a built-in function of the total space. Currently such furniture does not exist. Bibelots? They are unnecessary, meaningless. If functional design had more intrinsic beauty, there would be no need to use decorative objects which are merely a cover-up for aesthetic shortcomings."

Philippe Venet

A Man of Nuances. "Too much effect kills the effect," considers Philippe Venet. In his apartment the couturier has created an ambiance that reflects his personality as well as his fashion principles: purity of line with occasional boldness. For the sake of proportion he lowered the ceilings, and for extra depth he used mirrors. White gives an impression of space. Walls, curtains, sofa, and day bed are white. White again for the Braque signed lithographs. "Glass is unsubstantial in space. It leaves space undisturbed." The steel-based table placed along the mirrored wall is glass. "Four of them grouped in a square or set in a file make a dining table for twelve," he explains. Naturals, which Venet likes so much in fashion, appear in the delicate sand color of the Indian carpet and in the patina of 18th-century terra-cotta Chinese statuettes. The desired out-burst is provided by a striking canvas by Michel Warren. To balance the horizontal lines, a pristine metal arc, the work of Alex Liberman. Other things he dreams of only "because they are unapproachable," he deplores, "such as a Nicholas de Stael, a Picasso of the Antibes period, a Magritte for its madness, and a flock of sheep by sculptor Lalanne."

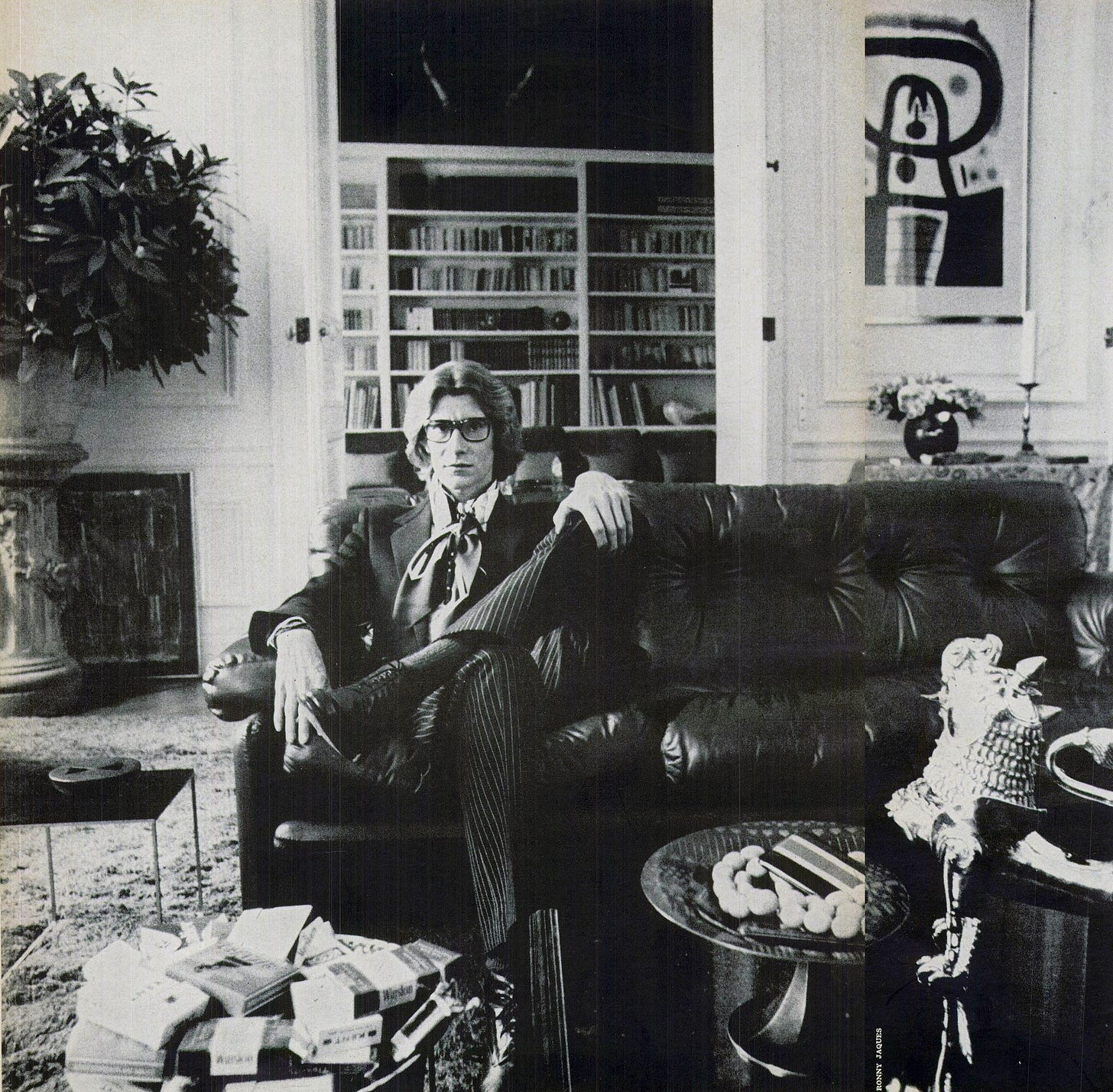

Yves Saint Laurent

His Own Man. The last thing Yves Saint Laurent intends to do with his apartment is to make it fashionable. To his mind, one's house should first of all be personal and last of all reflect the latest trends in decoration. "My house used to be pompous," he explains, "conceived for large cocktail parties. Now, I intend only that it be comfortable for my friends. I put in leather sofas and kept the fireplace as it was, ugly but functional." Walls are navy, chocolate, red, and white. If they are lacquered it is because he likes them that way, not because it is à la mode. Yves and his friends love to sit and eat on the floor. "My friends? They are mostly unknown artists." When he is not in Marrakesh, the Rive Gauche is his happiest derivative. "The Left Bank allows me to tune in with life. Here there is no show—the new life style of the young is a matter of attitude, not of age or money."

Coco Chanel

A Woman of Genius. The most extraordinary octogenarian in the world has found an escape hatch: a house near Lausanne where she rests, reads, walks, and thinks when she gets bored with Paris. It is comfortable, unpretentious, and completely "undecorated." Coco does not like set patterns for anything, least of all living. The outside is deceivingly conventional. Coco Chanel rather likes it that way. She thinks of it as camouflage—all the better for hiding. And to hide, when she wants to, gives her delicious pleasure. What helps her hide out in style—Coco's style—is a mixture of things she loves and brought here: deep-black and red lacquered antiques, Coromandel screens, Boulle furniture with more than a glint of bronze doré, French Renaissance sofa and chairs—all accented with elements of bamboo, trellis, and chinoiserie—decorative fantasy she uses like jewelry.