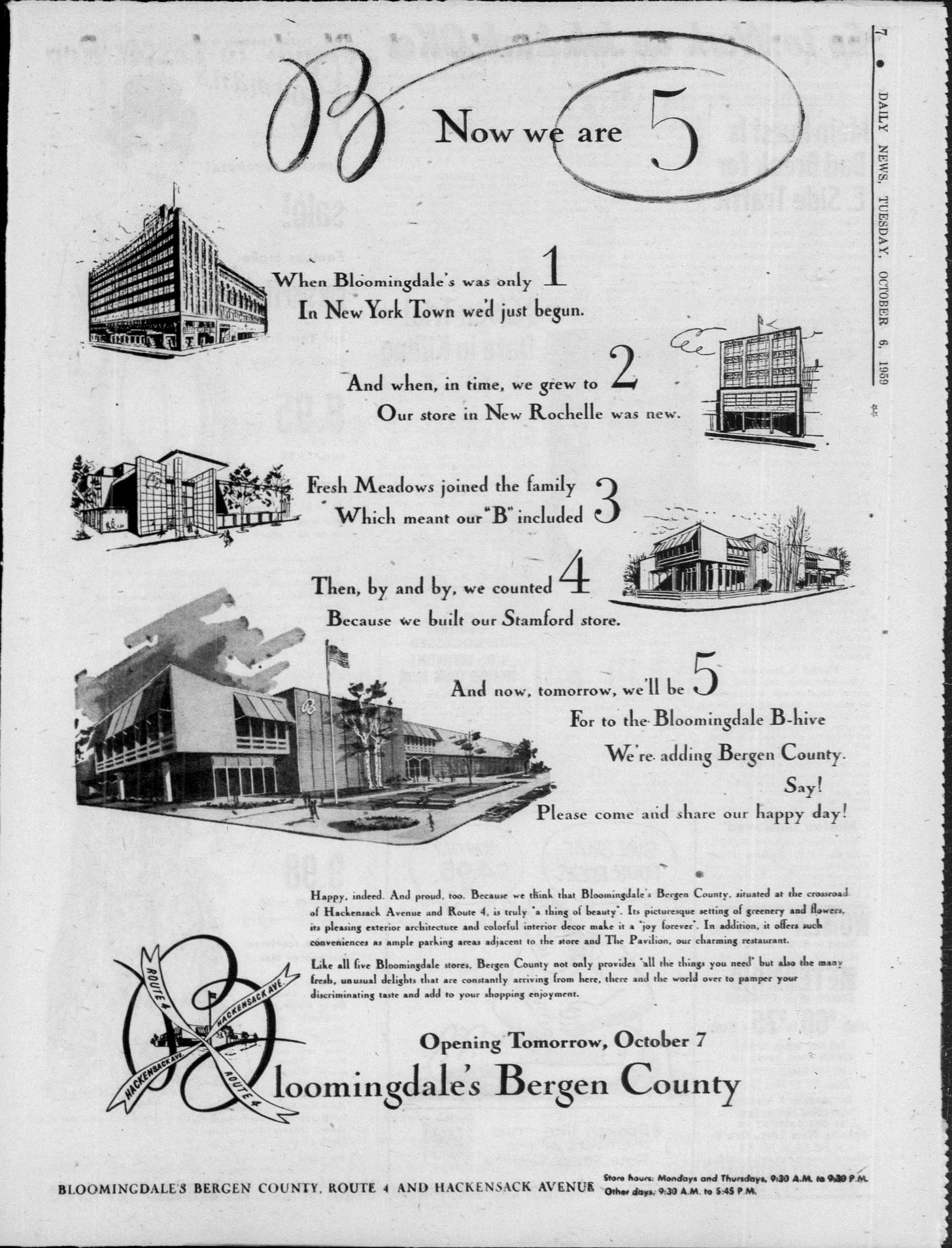

This was meant to go out last weeIn the years of peace and prosperity following the end of World War II, all retailers—and particularly department stores—wanted to get in on this newfound wealth. As it became apparent that GIs and their families were, for the most part, not settling in cities but instead in their environs, the department stores followed them. Bloomingdale’s was one of the first city department stores to establish branches—their first opening in New Rochelle in the late 1940s. Up until the early twentieth century, New Rochelle was a smallish town on the Long Island Sound in Westchester County, just above New York City. Due to its proximity and quick train journeys to Manhattan, by the 1930s New Rochelle was a fully-fledged city, and was both the wealthiest city per capita in New York state and the third wealthiest in the country. Bloomingdale’s purchased the former Ware’s department store on Main Street in December 1947 and took over operations at the beginning of 1948; built in 1914, the five-story brick building had over 100,000 square feet of floor space. Confusingly, Bloomingdale’s kept the Ware’s name for at least the first year they were in charge—Bloomingdale’s ads might mention that an item was “also available at Ware’s, New Rochelle” or that “Our Westchester Customers Will Find These Items at Ware’s.” Likely meant to provide some continuity for local customers whose families might have shopped at Ware’s for generations (it was founded in 1881), by not changing the nameplate Bloomingdale’s failed to make their expansion apparent, leading to less name recognition; they officially changed the name January 1, 1949. The nameplate wasn’t the sole issue—as Maxine Brady remarked in her 1980 book Bloomingdale’s, “It didn’t take long to determine that the purchase of existing stores could mean the acquisition of existing problems as well.” Forced to work within the limitations of a previously existing building, Bloomingdale’s found it difficult to renovate and reorganize in a way that broadcast their retail vision; it became apparent that if they wanted to expand, they would have to build their own stores. Up until the 2000s, New Rochelle was the sole Bloomingdale’s branch placed within an existing building.

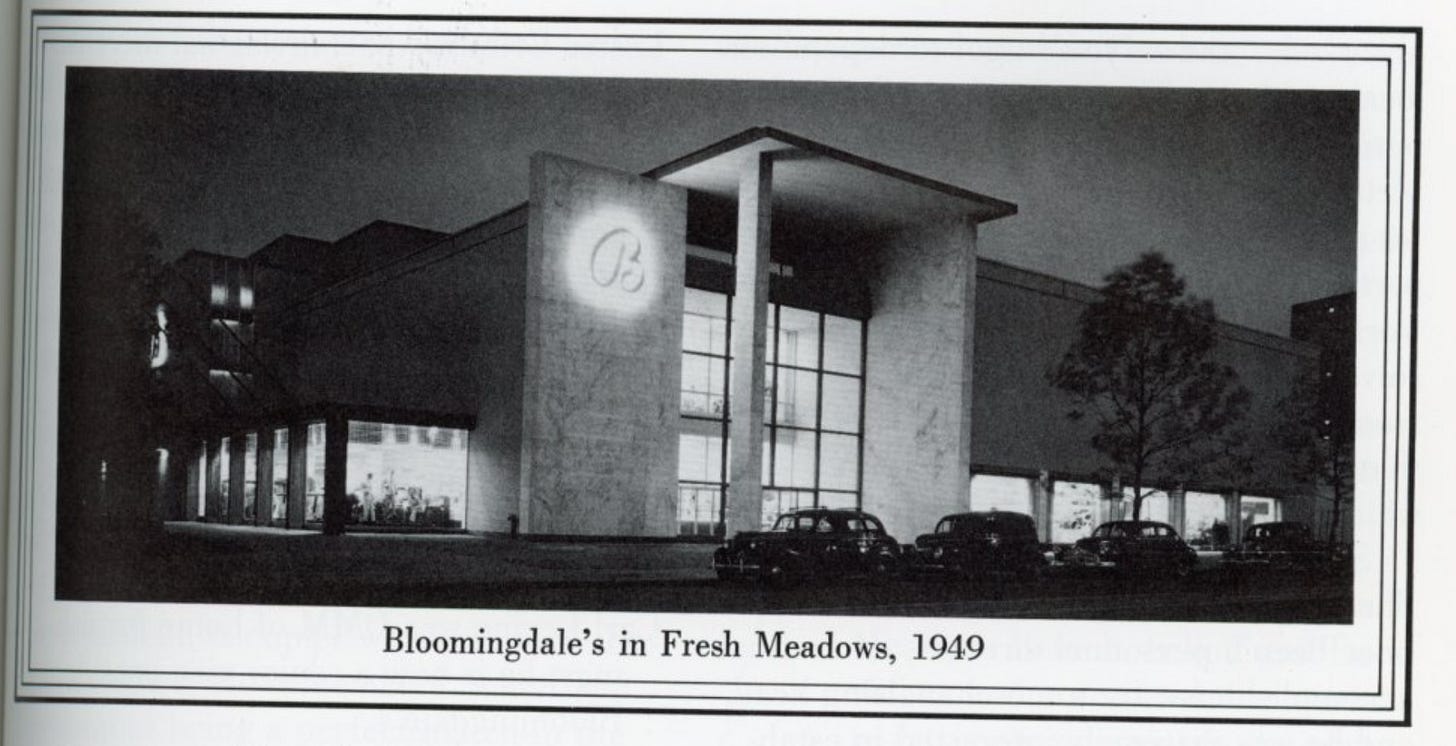

Prior to purchasing Ware’s, Bloomingdale’s had leased a plot of land in Fresh Meadows, a neighborhood in northeastern Queens. Primarily known as a farming community, a large golf course for rich New Yorkers was built there in 1921. In 1946, the golf course was sold to the New York Life Insurance Company who set out to build a housing complex and shopping center on the land—these were among the first of their kind in the United States designed primarily for automobile traffic, ushering in the new suburban postwar lifestyle. The Fresh Meadows Housing Development was built to house local WWII veterans. Adjacent to the housing development, NYLIC constructed a 12-acre shopping center—this is pre-mall, so all the stores were free-standing buildings within the larger site with Bloomingdale’s the sole department store. NYLIC hired Voorhees, Walker, Foley & Smith as the architects for the whole development including the stores, though Bloomingdale’s brought Kahn & Jacobs in as consulting architects. Announced in September 1947, construction took a year and half. In opposition to Bloomingdale’s flagship and the New Rochelle branch, Fresh Meadows was fiercely modern. Two stories (with a basement) of gray brick clad with white marble on the façade, soaring double-height windows welcomed shoppers through a colonnaded portico and into the immense, flowing space. By the rear entrance (with an identical double-height glass wall), was a covered canopy for baby carriage parking—perfect for the post-war baby boom. Twenty-five thousand people visited on opening day, revealing just how correct Bloomingdale’s suburban hunch was.

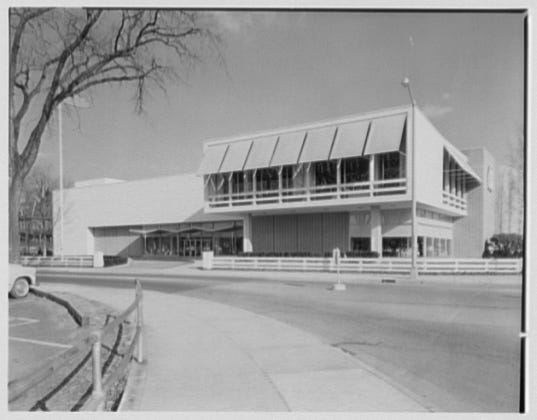

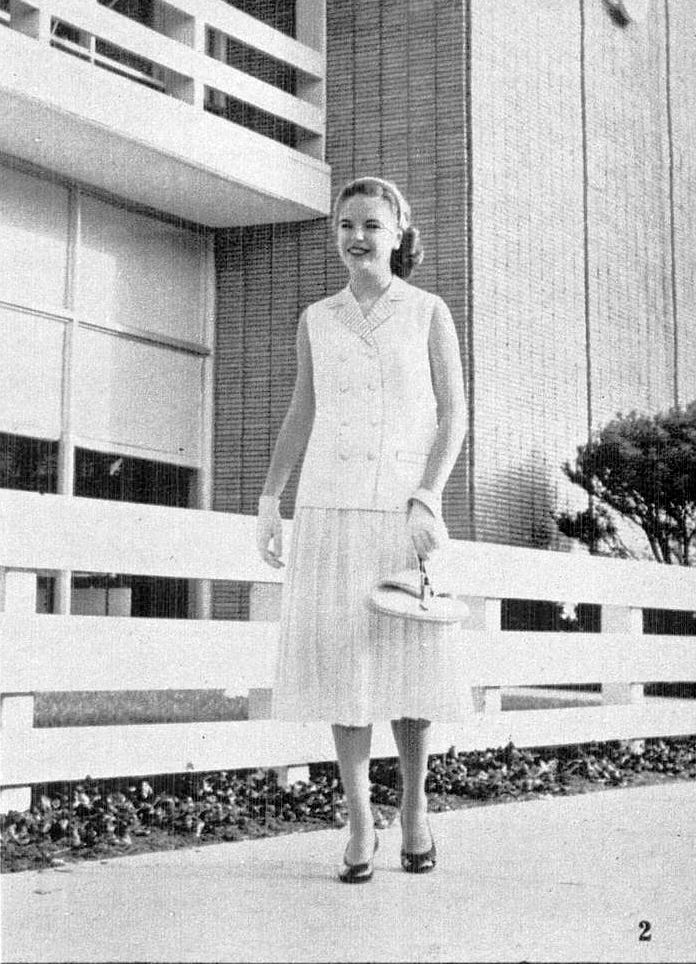

Bloomingdale’s next foray into out-of-town branches did not open until 1954. This time they brought in the Raymond Loewy Associates to design the building. I’ve written about Loewy previously regarding his redesign of Jay-Thorpe, but he does not appear to have been personally involved with the design of Bloomingdale’s Stamford, Connecticut, branch. Instead, William Snaith, an architect at Loewy’s firm, took the lead—closely collaborating with Bloomingdale’s director of store design, Helen Wells. Wells had previously been responsible for the interior of the Fresh Meadows location—a role she repeated here, in addition to setting the color palette for the exterior: pastels for both the outside and inside. Snaith designed the two-story store out of salmon-colored Roman brick with contrasting panels of common brick painted white. It was described by Women’s Wear Daily as a “300-foot-long, low-slung white-washed brick structure of 160,00 square feet.” In terms of setting, it was somewhere between New Rochelle and Fresh Meadows—located in downtown Stamford, with its pedestrian and bus traffic, there was also a very sizeable parking lot that could hold up to 1,000 cars, providing easy access for automobiles. Snaith told WWD, “There are few locations left where you can combine both as perfectly as we were able to here.” Stamford was very much a city in flux at that moment—the manufacturing that had grown it to 74,000 people by 1950 was in major decline, with most factories closing or moving to cheaper places down South. Due to its close proximity to NYC it was at that time very much a bedroom community (similar to New Rochelle and Fresh Meadows), yet at a much larger scale. The influx of corporations and financial companies that would totally reshape the city—particularly through a much-criticized urban renewal project in the late 1960s—was still in the future. Bloomingdale’s entered Stamford as the largest department store in town, into a downtown that was on the precipice of major decay.

Five years later, Bloomingdale’s ventured into New Jersey. Their fourth and largest branch opened in Hackensack, Bergen County, in October 1959. Again designed by William Snaith for Raymond Loewy, with assistance from Helen Wells, it followed the same modern, pastel aesthetic as Stamford: salmon-tinted and white-painted brick in a very modern style. The Paterson Evening News described it as “contemporary in design and has three entrances at street level, each canopied in wood. On the second floor are three glass-enclosed balconies, one of which is cantilevered beyond the street floor walls and forms a frame for the glass-fronted section that houses the Pavilion, a delightful restaurant seating 150.” As with the other purpose-built branches, it was fully air-conditioned with state-of-the-art elevators and escalators for ease of movement—and Wells continued her pattern of using different pastel colors to differentiate departments. Located on a large highway on the edge of Hackensack, this was a true suburban store, complete with parking for 2,000 cars.

Raymond Loewy Associates final collaboration with Bloomingdale’s (they also worked on a redesign of the flagship in the mid-50s) was its first furniture-only store in 1965, located just 100 feet from the Hackensack branch. Bloomingdale’s branches sold home furnishings (appliances, floor covering,s and housewares), but no furniture—Bloomingdale’s Furniture Wing was “an answer to the need in the suburbs for furniture stores of department-store scope.” Much smaller in scale, it was only 26,000 square feet including fourteen model room set-ups (six as window displays and 8 full interior rooms) along with around one hundred different partial settings of rooms; the Wing also carried the same brands at the same price point as the Manhattan store. Snaith designed the exterior to match the adjacent branch. Outside was a landscaped plaza and Romanesque garden, “where indoor-outdoor living is skillfully blended through furniture of period and traditional design.” As with the other branches, the Furniture Wing was an instant success.

Related reading:

Bloomingdale’s continued to open new branches, slowly expanding beyond the tri-state area and into other major cities. The fates of its first branch stores tie in with many of the major cultural shifts of the second half of the twentieth century. By the late 1970s, downtown New Rochelle was becoming a victim of urban blight. Bloomingdale’s had opened a large, new branch nearby in suburban White Plains in 1975, and management felt that there was little point in maintaining an old, difficult building on a half-empty main street. The closure of the Bloomingdale’s in New Rochelle in January 1977 is felt by many to have been the death knell for downtown; “New Rochelle's reputation as a merchant town in the mid-60s to early '70s, according to residents, has dwindled due to fear of crime, the closing down of major department stores, consistently below-average merchant mix, and stiff competition from the Galleria and White Plains Mall." After sitting vacant for 25 years, the former Bloomingdale’s building reopened in 2004 as 72 luxury live-work lofts that retain the Beaux-Arts limestone façade.

Bloomingdale’s closed the Fresh Meadows store in 1991, after 42 years of operation. While still profitable, according to then-chairman and CEO Marvin Traub, it "would require extensive renovations to remain competitive." Close to the more up-to-date Garden City, Long Island, branch, closing Fresh Meadows was an easy decision for a chain amid immense upheaval—fresh from a disastrous hostile takeover by Robert Campeau in 1988, Federated Department Stores (the owner of Bloomie’s) entered voluntary bankruptcy in 1990 and all stores were on a major expense-saving program (for more on the takeover and this period in Bloomingdale’s history, pick up a copy of Traub’s immensely interesting, Like No Other Store…) The building became a Kmart and then a Kohl’s; while there have been some exterior modifications, the original modernist structure is still clearly visible.

Another victim of the post-takeover fallout was the Stamford store. It closed in September 1990. In much the same way that Bloomingdale’s closure in New Rochelle destroyed its downtown, so was Stamford’s similarly affected. The chairman of the Stamford Chamber of Commerce told the New York Times that "Bloomingdale's was the anchor for that end of downtown." The newspaper went on to describe how, “Since the closing, the immediate neighborhood has suffered drastically. Shops on Broad Street facing Bloomingdale's empty windows have closed, leaving a clutter of ‘For Rent’ and ‘For Sale’ signs on some 30,000 square feet of retail space.” The site was taken over to become a mixed-use development before being sold to the University of Connecticut in 1994. By the time the remodeled campus opened in 1997, Stamford’s downtown was officially flourishing again and is now the “largest financial district in the New York metropolitan region outside New York City and one of the nation's largest concentrations of corporations.”

The sole survivor of the original branches is Hackensack. In 1977, an enclosed mall was built around Bloomingdale’s, with Bloomie’s greatly expanded to serve as one of the main anchors alongside a new Saks Fifth Avenue. Riverside Square Mall opened to much fanfare that March, with a Southern California décor. In the mid-2000s the original Bloomingdale’s Furniture Wing (now Home Store) was moved into the main Bloomingdale’s building, opening that space for more retail and restaurants. Now called The Shops at Riverside, the luxury mall houses brands from Bottega Veneta and Tiffany’s with Bloomingdale’s still the main anchor.