Since the death of André Leon Talley last week, my mind has been continually returning to a subject I often write on—ageism and the ease with which creative industries ignore their elders. The intersectionality of Andre’s abuse—racism, fatphobia, ageism—amplifies and intensifies each of these isms.

I keep thinking about André and how poorly he was treated by the fashion industry. I can only speak to what he wrote in his memoir, The Chiffon Trenches, which graphically lays out his side of the story. His continued love and respect for Anna Wintour, in the face of allegations of harsh ghosting by her, could be read as the love someone abused still has for their abuser—again this is just one side of the story, but I found it very painful to read his memoir when it came out in 2020 and equally painful to re-read this past week. Relationships are complicated, and those he had with Anna and Karl Lagerfeld seem particularly so. Both Talley’s friendships with Wintour and Lagerfeld ended when he no longer was useful to them; they had found younger, hipper or more successful replacements and felt none of the kinship bonds most of the rest of us hold dear—I feel like this comes through particularly clear in Wintour’s dispassionate remembrance of Talley on Vogue’s website.

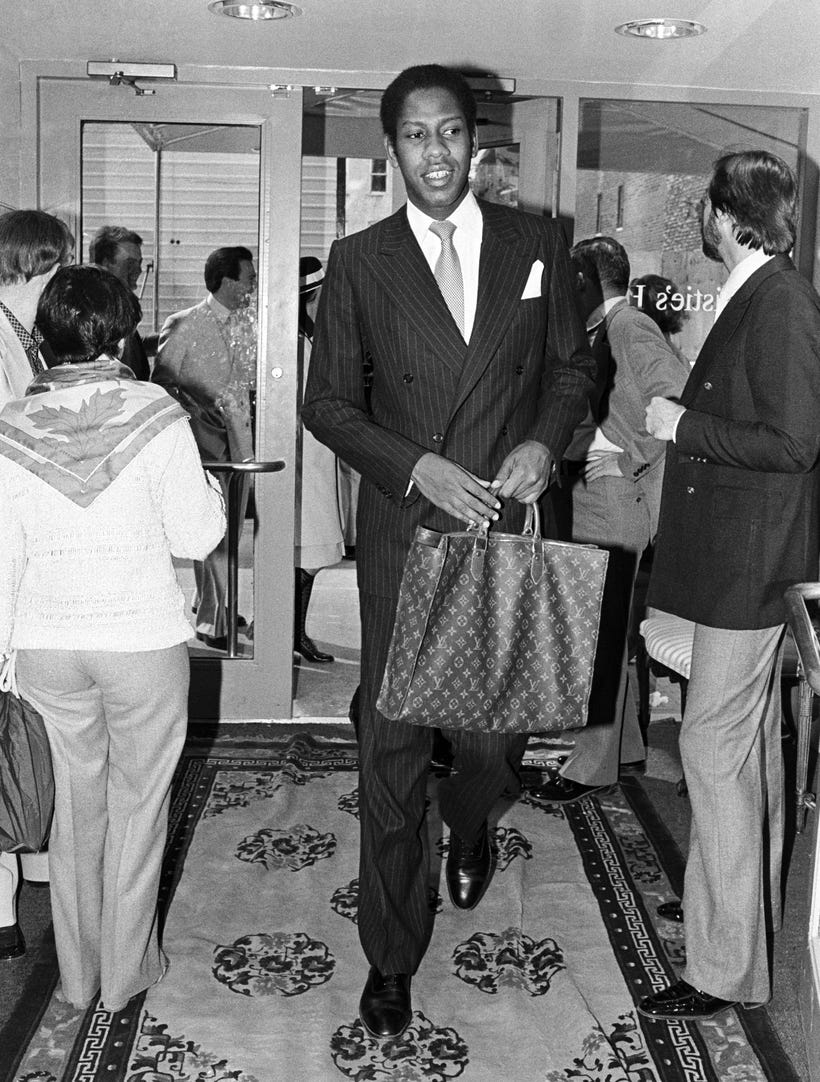

More so, I’d like to speak to the sense that he gave so much to an industry (intellectually, emotionally) that didn’t always reciprocate to the same degree. The fashion industry gave platitudes (this is particularly obvious in the many loving Instagram posts from fair-weather friends this past week), access to parties, glamorous clothes, but on an emotional level he very much gave his life to fashion and was thrown out of the inner circle once he was deemed “too fat” and “too old.” André gave his brilliance and his encyclopedic knowledge, his impeccable taste and his talent, to editors, designers and others who built their careers off of his skills—using that brilliance to elevate their work and, through that, their standing in the industry. To his socialite friends, he was an erudite, elegant walker who helped them bring some special elan to their couture wardrobes. In turn, he spent all his earnings on the trappings of the beautiful life—what he described as “the world of opulence! opulence! opulence! maintenance! maintenance! maintenance!” in 1994—which he did beautifully, as he had exquisite taste, but not without multiple bankruptcies. He gave up security and stability for beauty and a seat at the table of those with generational wealth.

With André’s unique, decades-long place among the firmament of fashion and high society, there was simply further for him to fall. Long before he turned to food or aged, he was defined by his race. As Hilton Als put it in 1994, ALT was “the only one”: “Talley’s fascination stems, in part, from his being the only one. In the media or the arts, the only one is usually male, always somewhat “colored,” and almost always gay. His career is based, in varying degrees, on talent, race, nonsexual charisma, and an association with people in power. To all appearances, the only one is a person with power, but is not the power. He is not just defined but controlled by a professional title, because he believes in the importance of his title and of the power with which it associates him. If he is black, he is a symbol of white anxiety about his presence in the larger world and the guilt such anxiety provokes. Other anxieties preoccupy him: anxieties about salary and prestige and someone else’s opinion ultimately being more highly valued than his. He elicits many emotions from his colleagues, friendship and loyalty rarely being among them, since he does not believe in friendship that is innocent of an interest in what his title can do.” ALT might have been at the time the creative director of Vogue (later an editor-at-large), but that did not protect him from racism—it simply became more veiled, more tinged with jealousy and fear. At the end of Als’ New Yorker piece is a description of some casual racism by LouLou de La Falaise—the socialite muse of YSL—toward André, who was supposedly her friend. The 2017 documentary, The Gospel According to Andre, further expounds upon the near constant micro- and macro-aggressions he dealt with throughout his career—“There’ve been some very cruel and racist moments in my life in the world of fashion. Incidents when people were harmful and meanspirited and terrifying,” he said in 2018—hostilities he fought off with the armor of perfect style and flawless manners.

As easy as it is to write a hagiographic remembrance post after a celebrity or icon (or former friend) dies, it’s also very easy to write an obituary/post that elides the problems they endured, especially later in life. Anguish, trauma and being forgotten get folded into single sentences, if they are even mentioned at all. His close friends have made clear in the past that ALT could be a difficult friend—from a 2018 profile, “Ms. von Furstenberg said, ‘you have to work at being his friend. It is not always easy. Sometimes he doesn’t call for months.’ He can be, according to many reports, as cutting and dismissive as he is warm and generous.” When reading The Chiffon Trenches his bitchy and isolationist shield falls away—his pain made vivid through his descriptions of an emotionally distant childhood, a difficult relationship with his mother and CSA. Traumatized and brought up in a culture that rejected the introspection of therapy, he was saddled with the shame of abuse through his whole life—choosing to reject love, romance and sex, to later find his comfort in food addictions. In many ways, this is why the fat phobia of the fashion industry, and his friends, towards him is so painful—he was suffering deeply yet they only cared what his size reflected on them when in public. The two interventions he discusses in the memoir—one by Anna and Vogue, the other by Lee Radziwill—are genuinely difficult to read, coming as they did from archly thin women obsessed with appearances.

For the past few years ALT was at risk of being evicted from his home of seventeen years. Due to his previous bankruptcies, Talley was unable to purchase a home; instead his friends, former head of Manolo Blahnik USA George Malkemus and his husband, bought a house in White Plains for “about $1 million on the understanding that Mr. Talley would live in it and pay Mr. Malkemus and Mr. Yurgaitis money each month.” According to ALT these payments were “an equity investment intended to result in his ownership of the house,” while Malkemus says they were rent payments. By 2020 Malkemus wanted to sell the house and Talley refused to leave, stating that the $955,558 he had already paid be put towards his purchase of it; Malkemus said Talley owed him $515,872.96 in back rent. Malkemus passed away in September; while a settlement was supposedly agreed in November, that settlement had still not been filed at the time of André’s death—you can read more about the case here and here. This is a complicated case and we only have court filings to provide the two sides, but it clearly reveals the perils of mixing business with friendship (which is in many ways the basis of the fashion industry) due to the awful falling-outs that often result. The “betrayal” by George Malkemus mimics that of Wintour and Lagerfeld to ALT (I am putting betrayal in quotes as this is very much based on ALT’s court filings; Malkemus would have had a very different perspective). All three were close friends yet also business associates of André; there to help him financially when he was of use to them, but happy to discard or evict him when it suited them.

I am reminded of an ALT quote from that same 2018 interview: “Fashion does not take care of its people.” Do any of the creative industries truly take care of their people? In that same interview he references how Josephine Baker died destitute; the same could be said for many others, in the past and currently, except now their death will be followed by a flurry of Instagram posts and then nothing. This is something that I’ve touched on before, a theme that has come up repeatedly in my podcast interviews—how easily creatives can be forgotten and discarded when they age, quickly replaced with the novel and young. This isn’t just an issue in fashion—my interviews, with people from all fields, have made that clear—but with fashion being an image-based industry, it seems more severe.

Looking for love in all the wrong places. ALT exceeded those he clung to in intelligence and grandeur, and was a magnificent pain in the ass by all accounts. Had he realized his superpower was his outsiderness, and sorted how to work it, the world might have come to his door, because we hunger for authenticity, even in the (s)hallowed halls of fashion. Godspeed, great man.

Thank you for this.

Thanks to programs like “Fashion Television” he seemed to be ubiquitous in the world of fashion. I mean was a Chanel show really a Chanel show if he wasn’t present for the run through? It wasn’t until later when I read about Vreeland and their time together at The Met that I realized, wow hard work and intelligence, not money or family connections. What a rare thing to see in that world. I remember some years ago while living in NYC, ALT was interviewing his friend Manolo at Rizzoli, the back room was incredibly packed but I still did my best to grab a look. Not for the shoe designer, but for the man the myth and the legend that was ALT, that presence, that voice. Just to feel that he was real and at one time all of that world was real.

Thanks for championing the not so young. It’s more important now than ever.